Black farmers in Georgia looking to benefits from massive aid package

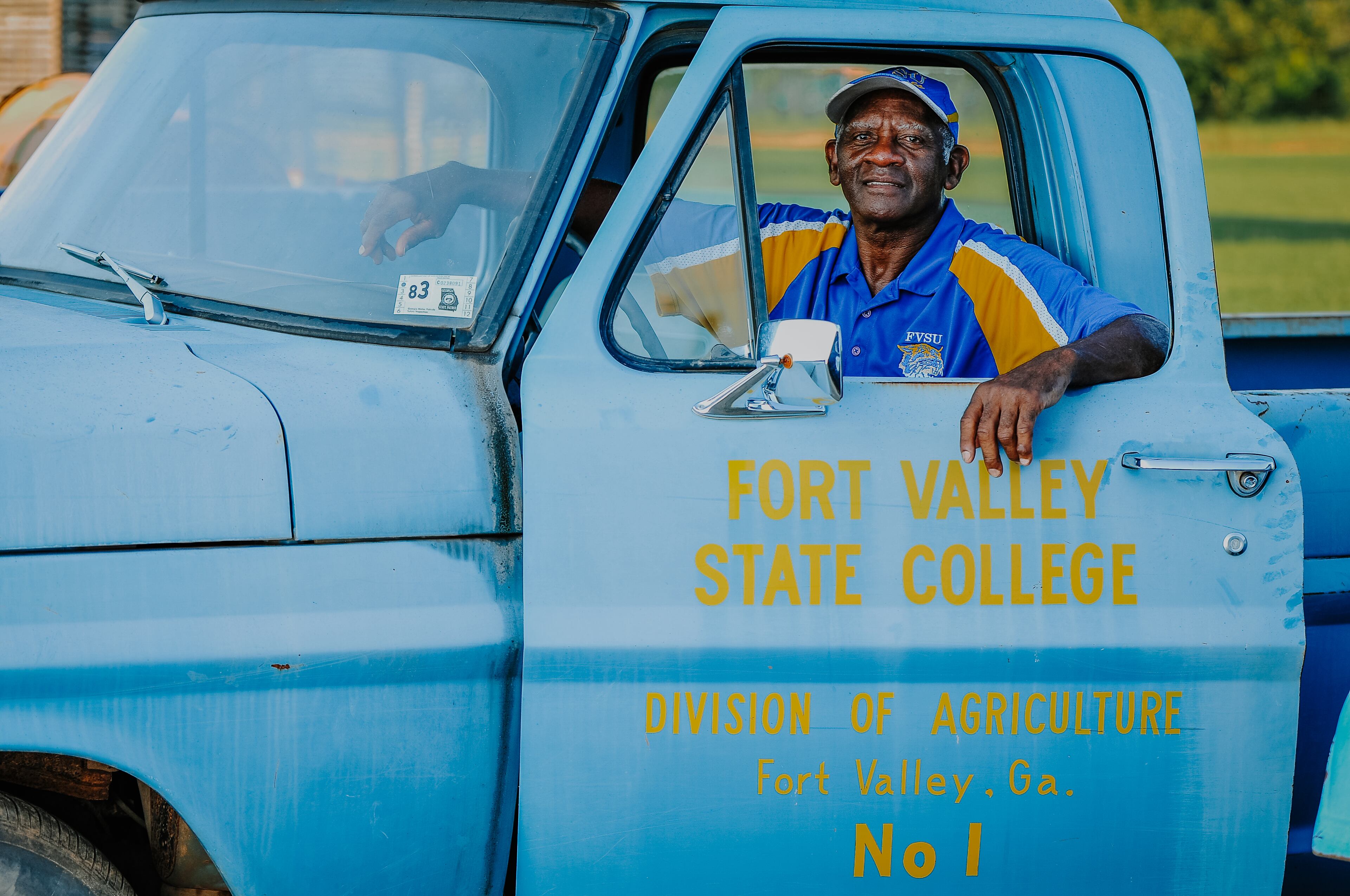

FORT VALLEY — As busy as Donnie McCrary is, his thoughts still drift sometimes to what might have been.

In 1974, as a 24-year-old Fort Valley State College graduate, he used a $200,000 loan from the Farmers Home Administration to buy 139 acres two miles from campus.

On it, he grew muscadine grapes, blackberries, blueberries, squash and sweet potatoes. But he was known for his collard greens, which sometimes grew heads as heavy as six pounds.

D.M. Farms, as he called, wasn’t big enough to compete against “the big boys,” he said. But it was productive — until a deep freeze wiped out his crops in 1985.

Unable to secure another loan, he lost everything.

Over the past century, Black farmers have lost more than 12 million acres of farmland, the result of systemic racism in lending and exclusion from agricultural programs, according to agricultural experts and the government’s own admission in court.

“I could not come back without any assistance, and it was devastating,” McCrary said. “You go to the bank and try to get something and you have a strike against you because you are Black. It was so obvious.”

Though far too late for McCrary, it appears that long-awaited help is coming for Black farmers and other growers who have faced disadvantages because of race or ethnicity.

A massive stimulus relief package recently passed by Congress and signed by President Biden includes $10.4 billion steered toward agriculture. Of that, some $5 billion is slated to go to disadvantaged farmers, about a quarter of whom are Black.

“You’ve got this systemic racism that basically put these people behind and they’ve never caught up,” said Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack. “This is the beginning of addressing that issue.”

Most of the money will go toward covering outstanding debt and offering training, education and technical assistance. A racial equity commission also will be formed to root out discrimination at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. And historically Black colleges and land grant universities will receive financial support for research and education.

“There has been discrimination,” said U.S. Rep. David Scott, chairman of the House Agriculture Committee. “And, while we have to be able to provide the money to pay down the debts, we also have to provide the training and support so they do not fall into this situation anymore.”

That involves teaching minority farmers how to recognize and understand the discriminatory practices that have hurt them, Scott said, “so they can make money and have the same doors open in the marketplace to sell their products as the white farmers do.”

Righting century-old wrongs

Throughout Georgia, Black farmers are hailing the legislation as groundbreaking. For many, the financial boost could mean the difference in failing or surviving.

Under the Trump administration, the billions of dollars in bailout money meant to help farmers suffering from the effects of the trade war with China primarily went to large operators, most of whom are white, according to USDA data. And Secretary Vilsack said Black farmers got only a tiny fraction — 0.1% — of Trump’s coronavirus relief for American farmers.

“Black farmers don’t want and need another loan,” said 67-year-old Alford Greenlee, who farms 52 acres in Dougherty County. “Letting farmers understand the difference between a loan and a forgiveness loan is important because most of us are struggling already.”

The legislation represents a step toward righting century-old wrongs, advocates for Black farmers say.

But not everyone is pleased.

No Republican voted for Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan. And U.S. Rep. Andrew Clyde, R-Athens, said the specific aid to disadvantaged farmers is racist.

“This provision should be a clear violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” Clyde railed in a speech on the House floor. “It is shameful and, in my opinion, illegal. I cannot justify conditioning relief aid based on race and ethnicity. This is not equality under the law. Federal aid dollars should be colorblind.”

The new aid revisits previous forays by the government into compensating Black farmers for past wrongs.

A class-action lawsuit filed by North Carolinian Timothy Pigford in 1997 against then-Agriculture Secretary Dan Glickman resulted in a consent decree, which was supposed to provide restitution to Black farmers who were the victims of USDA racial discrimination between 1983-1997.

Critics said the payout program was rift with fraud and that people who weren’t even farmers applied and got money. Others said the payments were insufficient and still left thousands of Black farmers in debt, undermining their ability to create generational wealth.

“This bill addresses the inequities and injustices of Pigford,” said Tracy Lloyd McCurty, executive director of the Black Belt Justice Center in Washington, D.C. “But, when we start talking about what is owed the Black farmer, we are just getting started. The debt cancellation came 30 years late.”

The seeds of the new bill came from Sen. Raphael Warnock’s Emergency for Farmers of Color Act.

“I’ve spent a lot of time in rural Georgia, and I’ve heard firsthand from people in these communities how, for too long, they’ve felt left behind and discriminated against by our federal government,” Warnock told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Warnock notes that, over the last century, the number of Black-run farms has decreased 96%. According to the USDA, only 48,697 of the country’s 3.4 million farmers are Black.

Only 2% of all agricultural land is owned by Black people.

Veronica Womack, who works with African American farmers as the executive director of Georgia College & State University’s Rural Studies Institute and the founder of the Black Farmers’ Network, said those numbers are stunning.

According to the USDA’s 2017 Census of Agriculture, the average net cash income for Black farmers in Georgia was $8,137 in 2017, compared to $69,000 for white farmers. Most Black farms in Georgia range from 10 to 179 acres, much less than the statewide average of 235 acres. Only 63% of Black farmers in Georgia have internet access.

The numbers have been made even starker by the COVID-19 crisis, Womack said.

2,870 — Black farmers In Georgia, ranks 5th highest in country

48,697 — Black farmers in the U.S., out of 3.4 million in the country

10 acres-179 acres — size of Black-owned farms in Georgia

235 — average size of all farms in Georgia

12 million — acres lost by nation’s Black farmers over past century

Source: USDA

James Ford, a former USDA employee who now consults with Black farmers, said the COVID-19 crisis has been a curse and a blessing for small farmers.

On the one hand, they’ve had to become more technologically savvy, using platforms like Zoom to access educational programs and technical assistance.

“But the negative is that agents from the USDA have not been able to visit the farms,” said Ford, the owner of Square O Consulting. “There have also been issues that all farmers have faced in marketing their beef, because the slaughterhouses were shut down. They didn’t get the market they expected.”

‘We need more of us’

In Georgia, there are 2,870 Black farmers, the fifth-highest number in the U.S. Many of them, like LeMario Brown, live in Central Georgia.

Brown, who also serves as Fort Valley’s mayor pro-tem, doesn’t look like your typical farmer. On an early Friday morning, he is wearing a flashy polo shirt and designer jeans. But he trades his Jordans for a pair of work boots as he walks his land.

He scoops up a bucket of feed, walks to a pen, then, with a combination of bucket shakes and verbal clicks, calls his cows and goats to breakfast.

At 35 years old, Brown essentially has taken over his family’s small 10-acre farm, located behind his parents’ house. Aside from the two cows and eight goats, he has a couple of hogs and a coop full of egg-laying chickens, all watched over by a chocolate lab named Charcoal.

He wants to build the family farm to at least 50 goats, five head of cattle, 20 chickens and more pigs.

“I am in a good area. We have minimum competition when you are talking about small African American farmers. But I am trying to change that,” he said. “We need more of us. This bill will benefit us all.”

Because his family farm is so small, Brown doesn’t have much debt. But he and other farmers are excited about legislation and are studying ways to get access to some of the funding.

‘We can’t wait for the question’

Part of figuring that out rests on the shoulders of Ralph Noble, the dean of FVSU’s College of Agriculture, and Mark Latimore Jr., who runs the cooperative extension program.

“It is very critical that we do what we need to do here to make sure our farmers are trained and positioned right for the market,” Latimore said. “We are sifting through the relief bill now, looking for information so we will be able to intelligently talk to the farmers. If it does what is outlined in the bill, it will be a major boost for African American farmers.”

FVSU is one of the biggest farming operations in the area, with 1,200 of the campus’ 1,300 acres devoted to agriculture. The university works closely with the area’s Black farmers to provide information on traditional farming methods and bring them up to speed on technology and policy.

“Some of the farmers won’t read that bill, so we are relied on to be the interpreters. They don’t always have the best feel of the USDA, but they trust what we say,” Noble said. “In some cases, we can’t wait for them to ask a question. We have to present it to them.”

Government aid packages could have been a game-changer for McCrary, but he’s moved on.

He has retired to Albany now, where he mentors young Black farmers. He travels back to FVSU regularly to do work for the Cooperative Extension Program.

Sometimes, he drives past his old farm.

Sometimes, he stops and imagines what could have been.

“I would be a collard green specialist with several warehouses where I would be buying and selling them by the semi-load,” McCrary said. “I would be a millionaire — the collard green king. But it is hard to come up that road being Black.”