Retired Judge Paul L. Brady grew up hearing stories about Bass Reeves, the legendary lawman and one of the first Black deputy U.S. marshals west of the Mississippi River.

“Bass was by far the best candidate to be working out of that court,” said Brady, 93, Reeves’ great-nephew who lives in Atlanta with his wife, Xernona Clayton, a civil rights activist and founder of the Trumpet Awards. “To give a Black man a gun and the authority to shoot white people. That was unheard of.”

For more than three decades as a deputy U.S. marshal from 1875 to 1907 and later as a police officer in Muskogee, Oklahoma, Reeves was every desperado’s worst nightmare in the Indian Territory of what is now Oklahoma.

It’s said that he killed between 15 and 20 outlaws and arrested more than 3,000, men and women, earning a substantial sum for the times in fees, more than many of his white counterparts, according to historians and folklorists.

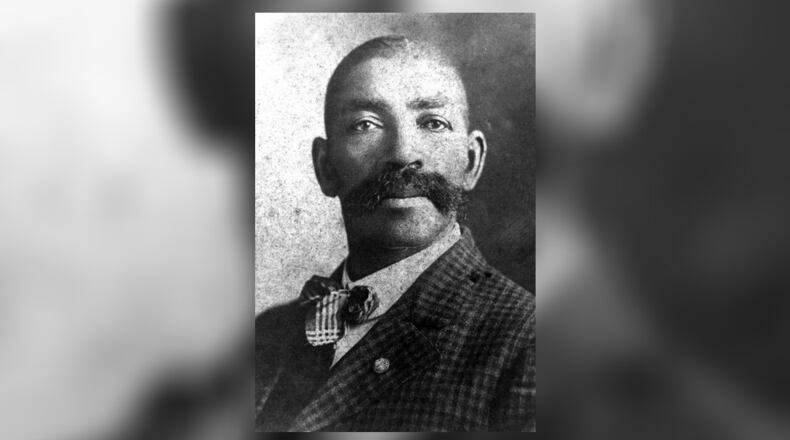

Credit: U.S. Marshals Service

Credit: U.S. Marshals Service

One of those people arrested, historians say, was his own son, who was accused of killing his wife.

Reeves, who towered over others at more than 6 feet tall and sported a bushy walrus-styled mustache, sometimes wore disguises to catch thieves, killers and the like who fled to the Indian Territory to escape the law. He had many close friends among the Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, Chickasaw and Choctaw, who sometimes assisted him in the hunt.

“I knew he respected them (Native Americans) and they respected him,” said Brady. “They did not like the white deputies because they looked down on them, so they helped Bass,” who was fluent in several of their languages.

Brady said he’s been approached by Hollywood types about doing a film project on Reeves.

As with many stories about the old frontier, sometimes it’s hard to separate fact from fiction. And, perhaps, the truth is somewhere in between.

Popular culture and Hollywood often focused only on whites in the Old West, but Blacks played a significant role as well, said historian Art T. Burton.

A few Westerns have featured Black characters, and actors playing Reeves have been featured in film and TV series such as “Hell on the Border,” and in the opening scene of “Watchmen.” The feared deputy marshal character will also have a role in an upcoming Netflix project, an all-Black Western called “The Harder They Fall,” loosely based on Black cowboy Nat Love and co-produced by Jay-Z.

Credit: Alyssa Pointer / Alyssa.Pointer@ajc.com

Credit: Alyssa Pointer / Alyssa.Pointer@ajc.com

There’s a 25-foot statue of Bass on his horse with his rifle and dog at his side that stands in Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Some believe the fictional character of the Lone Ranger was modeled after Reeves. Brady, though, doesn’t think there’s a connection.

“That is simply not true,” said Brady, who has written a book about his famous relative, “The Black Badge: Deputy United States Marshal Bass Reeves.”

Most Sundays when the weather was bad, Brady’s dad would relax in his favorite chair, pull out his pipe and entertain the children with stories about Reeves’ daring exploits. Reeves took on the role of a surrogate father to Brady’s dad after the death of the elder Brady’s father.

Credit: Alyssa Pointer / Alyssa.Pointer@ajc.com

Credit: Alyssa Pointer / Alyssa.Pointer@ajc.com

Reeves might be working the territory for a month or so at a time. Then he would come to visit the family at the horse farm outside of Van Buren, Arkansas. He would take the boys up in the mountains to go hunting and fishing. While he was tough when chasing criminals, he was devoted to his family and was kindhearted.

Still, “he was a pretty strict fellow,” Brady said his dad told him. “He had a dog that was with him all the time and he wouldn’t allow children to touch that dog. He (the dog) could be that vicious. He had to be, Bass would take him out in the territory to watch the prisoners. It was a big, black furry dog and he was highly trained.”

Reeves was born into slavery in northeast Texas in 1838 or 1839, said Brady. Some details about where he was born vary.

As a young man, Reeves escaped to Indian Territory in what is now Kansas and Oklahoma, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Credit: U.S. Marshals Service

Credit: U.S. Marshals Service

Because he knew the area so well, he sometimes worked with the white deputies and was paid, said Brady. This was before he became a deputy U.S. marshal.

Dave Turk, historian for the U.S. Marshals Service, said Reeves was hired, interestingly enough, at the behest of Judge Isaac C. Parker, also known as “Hanging” Judge Parker, who “had a big hand in selecting deputies, which was unusual for any judge. He had an iron-clad hold on that district.”

“He was the greatest lawman in the Wild West,” said Burton, author of “Black Gun, Silver Star: The Life and Legend of Frontier Marshal Bass Reeves.”

“You can’t compare him to anybody. He was the baddest badass you could ever think about. He shot people from a quarter-mile away with a Winchester rifle,” said Burton of Illinois, who first heard about Reeves as a youth when he visited relatives in Oklahoma.

The stories about Reeves are legend.

One time, Reeves arrested 17 horse thieves — all at one time, said Burton.

Another time, while working in disguise, Reeves pretended to be a farmer. Near the criminals’ hideout, he intentionally drove his wagon into a ditch and called out for help, said Burton. When the men came out and lifted the wagon, he pulled out his gun and arrested them.

Reeves also saw a bit of trouble himself. He was once accused of shooting to death his cook after an argument. Some say it was accidental and Reeves was eventually found not guilty. His nephew, Johnny, testified on his behalf.

“He was one of my personal heroes,” said Rob Sheppard, an instructor and gunsmith at the Marietta retail outlet for TruPrep, a retail store dedicated to wilderness and disaster-survival tools and apparel, including camping gear.

Credit: Alyssa Pointer / Alyssa.Pointer@ajc.com

Credit: Alyssa Pointer / Alyssa.Pointer@ajc.com

Sheppard spent roughly 30 years in local and federal law enforcement and is Native American. “He was one helluva gunfighter. He seemed like a real straight arrow and not all lawmen were back then. Doing what he did wasn’t easy for a Black man to do.”

Near the end of his deputy U.S. marshal career, life had changed. Racial violence was increasing in some areas out West.

And years earlier, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation.

“Sure, he may have been challenged because of race, but in Indian Territory, race was not so much of a factor,” Turk said. “You were hired because of need. Some of the deputies they had in the territories simply weren’t up for the job.”

Reeves died in January 1910 in Muskogee, Oklahoma, in his 70s. He reportedly died of kidney disease.

There have been several efforts to locate Reeves’ grave. Both Brady and Burton think he might be buried in a Black cemetery in the Muskogee area.

So far, though, his body has never been found.

Another Western mystery.

BLACK HISTORY MONTH

Throughout February, we’ll spotlight different African American pioneers ― through new stories and our archive collection ― in our Living and Metro sections Monday through Sunday. Go to AJC.com/black-history-month for more subscriber exclusives on people, places and organizations that have changed the world, and to see videos on the African American pioneers featured here each day.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured