Editor’s Note: This story first appeared in the Atlanta Constitution on Nov. 1, 1985.

PLAINS, Ga. - The infield where the president once pitched softball and White House aides tagged the bases is now covered with weeds, blown dry and lifeless by the winter winds.

On Georgia 280, the only highway through town, a weathered sign leans against a building and proclaims it as "Billy Carter's Former Station." But Billy isn't pumping gas or drinking beer there anymore. He's moved to Waycross and the mobile home business.

For four years, the world was fascinated with Plains and Jimmy Carter, and the impact of that fascination on this village set amid the peanut fields of southwest Georgia was immense. A seemingly endless caravan of the curious converged on the one-block-long commercial district, hungry for souvenirs, food and glimpses of the first family or any of its cousins.

Today, the ball field and gas station stand as timeworn reminders of an exotic era gone by. Most tourists stick to the interstates now, prompting those who hustled quick profits off Carter's famous smile and country-boy heritage to move on. When tourists do stop to poke around, they number in the dozens on a busy day.

RELATED: Guide to visiting Jimmy Carter National Historical Park in Plains, Ga.

Where is Plains, Georgia?

Plains, the South Georgia hometown of Jimmy Carter and his wife Rosalynn is located in Sumter County along U.S. 280. It is about 150 miles southwest of the the Carter Presidential Library in Atlanta, about 10 miles west of Americus and about 40 miles northwest of Albany. If you are making a tour of presidential historic sites, the Jimmy Carter site is about 70 miles from Warm Springs, site of Franklin Roosevelt’s Georgia retreat, the Little White House.

No more traffic jams

Residents hope that current efforts to include several properties in town into a National Historic Site in Carter's honor will pay off. It might bring a fraction of the tourists back as they come to tour Jimmy and Rosalynn's house, or his birthplace, high school or the train depot that served as his campaign headquarters.

Earlier this week, National Park Service officials were in town researching information for the legislative package necessary for the site.

But for now, Plains is as quiet as when Carter was still Georgia’s governor.

"It used to be really bad, " said Shelby Gray, a waitress at the Kountry Korner. "There were traffic jams in Plains." She fetches a barbecue plate for a customer and continues. "We don't depend on the tourists anymore. We have seafood on Friday and Saturday nights, and that gets folks from the surrounding counties."

Maxine Reese, who focused her considerable energies into marshaling Carter's campaign Peanut Brigade, recalls those earlier days with a touch of fondness, but little regret that they're over. "We used to say we could sit on the depot platform and watch the world go by, " she said.

She still stays busy, interrupting her conversation to take phone calls about Plains' centennial celebration, which she is organizing for May.

"Miss it? No, but I'm proud that I was part of it. We knew when he was elected he wasn't going to serve forever. It was a very exciting time. You look back and you're glad you had it. . . . " Ms. Reese pauses a moment, her mind flipping the pages back several years. "We had a party everytime Jimmy came home."

Queries for cousin Hugh

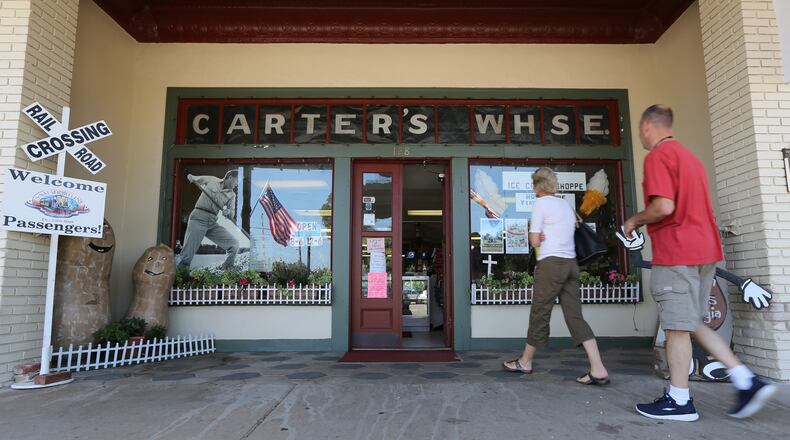

If there is one point in town that tourists still gravitate toward, it's Hugh Carter's Antiques. A congenial man, polite and patient, Hugh Carter will put down his copy of the National Enquirer and attend to any questions. "I'm his first cousin, yes sir, " he told a gentleman from Detroit. "He's guarded like a prisoner, " he said to the young couple from Wisconsin. "We grew up like brothers, " he confides to someone else.

“Most people want to know where he lives and if he’s in town, " said Hugh, who succeeded to his cousin’s state Senate seat in 1966, the year Carter ran unsuccessfully for governor.

The store is a spacious display of antiques, collectibles and no lack of books and post cards by and about the Carter family. But Hugh Carter spends most of his time sitting on the stool behind the cash register, fully aware that he is the store's biggest drawing card - the man with the inside detail, the colorful anecdote, the relative who just "saw Jimmy and Rosalynn at church last night."

Carter was in business years before his cousin became presidential timber. Like other merchants, he is acutely aware of the effect the 5,000 tourists a day had on a town of 650 people. His own store boomed during those years, requiring him to employ seven people just to handle the flow.

But Hugh Carter’s main business is a huge worm farm, an enterprise of no special interest to tourists and not dependent on anyone’s political fortunes. Life magazine even did a story on the operation in the 1950s.

Others were not so lucky. "I had three stores opened in one year, " says John Williams, a local man who capitalized on Plains' hometown boy. He has closed one store and is getting ready to close another. The third, a grocery store adjacent to the Kountry Korner, will probably remain in business. "Most of the stuff is local traffic, " he says.

In addition to the stores, "we had three tour services at one time. They are all gone. The whole main street was filled with souvenir shops, including a bunch of guys out of Missouri. There was another restaurant at one time. She sold out to a guy from Texas, and he went bust, too."

Other souvenir shops that once blossomed have left the same empty storefronts that greeted the curious when Carter first began his presidential campaign in 1975.

Some investors in the town were of another nature. One woman from California purchased three houses in town after Carter was elected. She currently rents one to the Secret Service, but has it on the market for about $100,000. "That price is way out of line for here, " Hugh Carter said. He mentioned that someone else bought farmland nearby and is trying to sell it for $2,000 an acre, an almost unheard of price for the flat territory that envelops Plains. Canadians have even bought property in the community, hoping to profit off the 39th president.

No interviews for Amy

"It's nice now, " said John Williams, who is mostly dependent on his peanut shelling operation on the edge of town. The peace and quiet have settled in once again. While it would have been nice to continue the other stores, he said, "it was getting old."

On the edge of town, a nondescript house has been converted to offices for Jimmy Carter and his local staff. Cumbersome stacks of mail addressed to The Honorable Jimmy Carter balance precariously on a couch, while a woman cradles a phone and apologizes to McCall's magazine that "No, I'm very sorry, but Amy is not giving any interviews."

"When Rosalynn and I walk downtown there might be four or five autos filled with tourists that will stop and shake hands and take our photos, " said Jimmy Carter, who has spent part of the morning out looking at some of his property. The town, he said, "is much more stable now. That may be disturbing to local merchants but I think it is adequate."

He says that whatever business tourism brought into town, it was business Plains "would not have experienced otherwise."

Carter feels the town has bounced back well. If there is any post- presidential depression among the townfolk from no longer being able to hobnob with celebr ities, he hasn't noticed it. "That time brings back pleasant memories . . . but the fact that it's still not happening is inevitable. It's not an unpleasant thing, but a pleasant thing.

"That's the way I think it ought to be." Anyway, he said, "The local people are very resilient."

Back at the Kountry Korner, owner Bobby Salter finished his lunch and hunched over the table to chat. Seated nearby was Ed Smitherman, a Secret Service supervisor, who dropped by for coffee after picking up a prescription at the town pharmacy.

The Secret Service agents, Salter and others in town have formed a local club called the Cornshuckers, a loosely knit organization of men whose sole purpose for the monthly meeting is just an excuse to "attend all meetings" and "say what you want to, " according to the official membership certificate.

It may not sound like much, but it passes the time nowadays in Plains.

After all, said Maxine Reese, “It takes a helluva lot to impress us now.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured