Hannah Palmer stood in a field of waist-high wild flowers on Monday, the sun beaming on her face, and imagined the setting one day becoming College Park’s first nature preserve.

The seven-acre tract off Willingham Drive near the city’s border with East Point in South Fulton County is now dominated by colorful brush of pinks and purples, a mishmash of tree varieties and chirping frogs.

But it’s the site’s main feature — the headwaters of the 344-mile Flint River, Georgia’s second longest — that has Palmer fast-forwarding to a verdant future.

“This is where it starts,” said Palmer, who heads Finding the Flint, a group dedicated to the river’s rebirth. “That’s why it’s such a symbolic site. From here is where it gets bigger and wilder.”

After 80 years of the river’s beginnings in metro Atlanta being obscured by development and expansion of the world’s busiest airport, south metro leaders are hoping to turn back the clock and make the Flint a quasi-Atlanta Beltline of trails, pocket parks and the nature preserve. The river runs through Fulton, Clayton and Fayette counties.

That dream was boosted in late April when MARTA agreed to sell the Willingham tract to College Park for $218,000 for the nature preserve and an outdoor classroom. MARTA bought the property, which is right next door to the prestigious Woodward Academy private school, in 1985 to manage stormwater from the then-new East Point train station, the transit agency said.

“MARTA believes that the mission of Finding the Flint and the mission of MARTA are absolutely complementary,” MARTA General Manager and CEO Jeffrey Parker said in a release announcing the sale. “From reducing flooded streets which can sometimes impact the reliability of our bus service to helping people have additional routes for walking and cycling in the area, MARTA is pleased to be able to contribute in this way.”

College Park Mayor Bianca Motley Broom said MARTA’s gesture is much appreciated.

“MARTA’s willingness to allow us to develop this parcel into a lush greenspace is another step toward building the community we deserve,” she said. “It is a win not only for College Park but for the entire region.

Business, residential driver

College Park Economic Development Program Manager Tasha Hall-Garrison said developing the property could also drive to the area residents and businesses that value parks.

“COVID has shown the necessity for all of us, whether it’s a commercial entity or residential, to have a greenspace,” said Garrison, who added College Park has received an $800,000 EPA grant that can be used to assess and clean up the property. “This is a great collaboration between Finding the Flint, MARTA and the city of College Park to enhance the quality of life to all residents.”

The Flint, which runs all the way to the Florida border, was an integral part of the southside in the late 1800s and early 20th century, Palmer said. Mills and railroads were built around it and in 1909 Coca-Cola founder Asa Candler constructed the first Atlanta Speedway racetrack next to the headwaters.

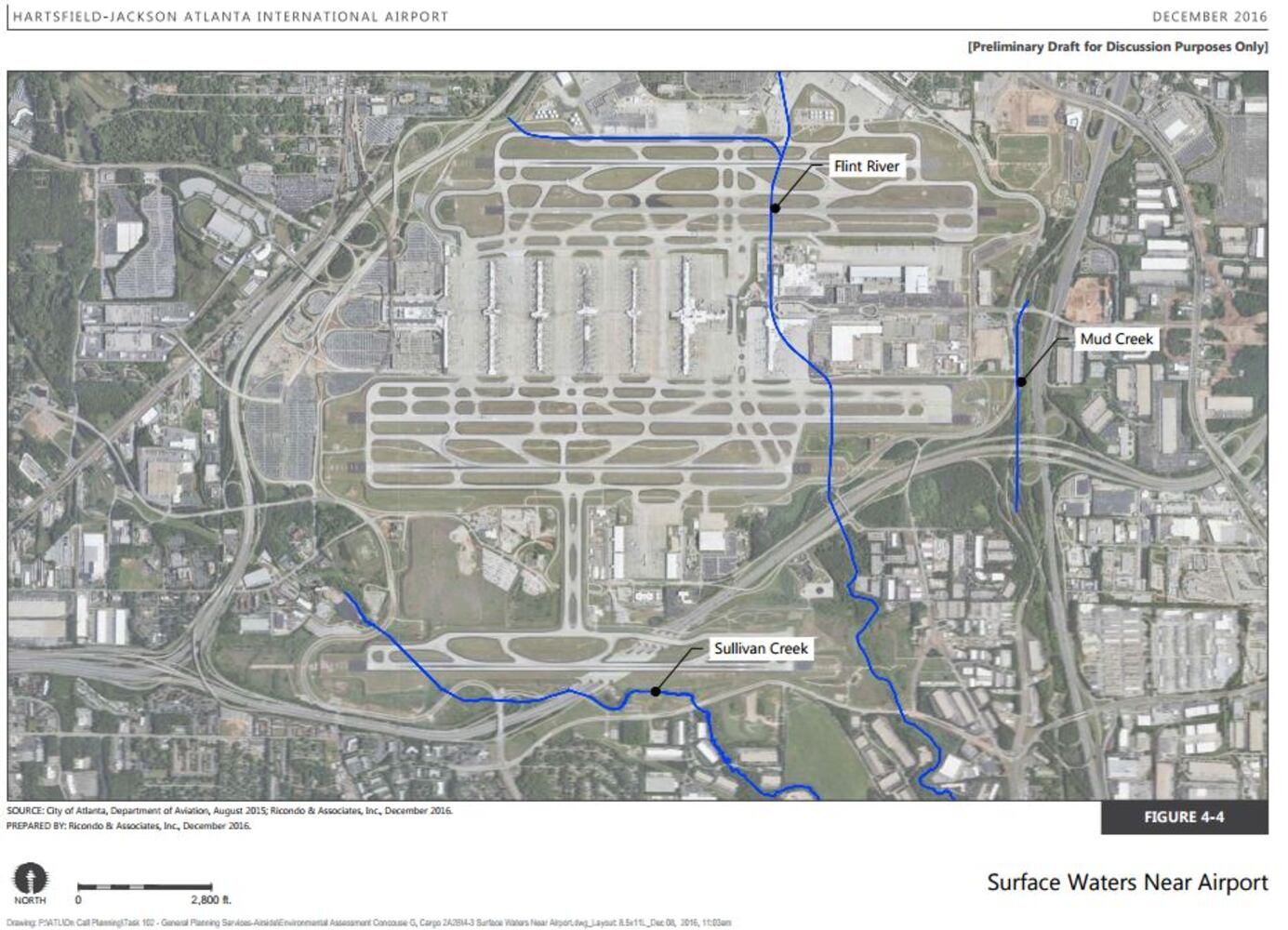

But after the Atlanta Municipal Airport extended its runways across the river in the 1940s, the Flint began to disappear into pipes and culverts. Great stretches are buried under Hartsfield-Jackson’s runways and about 1.2 miles were fenced off in 2004 after construction of the airport’s fifth runway.

“What gets me is like these [streets] are paved right up to an inch of the creek,” Palmer said, standing by portion of the river that runs along Willingham but is obscured from passersby by brush and trees. “Now we require a bigger buffer just to manage flooding.”

The headwaters won’t look like much of a river, even if the preserve is built, Palmer and other said. It’s more like a creek in College Park because it doesn’t pick up tributaries such as Mud and Sullivan creeks until it gets into Clayton County around Forest Park and Riverdale.

But Palmer’s dream, which is shared by others including Aerotropolis Atlanta Alliance, a business group helping to promote south metro development, is that the future nature preserve will open the door to other parts of the Flint to become part of a trail and park system.

“I think Atlanta is doing what most major urban centers are doing, which is like trying to find a way to preserve these areas while we still can because they just add so much quality of life,” she said.

Community support

College Park resident Tom Fulkerson sees that potential. Many southside residents travel to Midtown’s Piedmont Park and the Beltline or other parts of the metro to take advantage of greenspace that isn’t as abundant around the airport area.

“The one thing that we have been deprived of on the south side is amenities,” he said, adding that it’s a shame because the area has many historic sites that could benefit from the destination appeal of greenspace.

Noel Mayeske, a lifelong College Park resident, said he didn’t know about the Flint until Palmer and others began advocating for its revival in 2017. Because it has been hidden for so long, parts that are visible along side streets or in acreage behind subdivision looks like an unknown creek.

“When you think of College Park or East Point or Hapeville, you don’t necessarily think of a river,” he said. “We’ve taken this amazing resource and said, ‘OK, We’re going to put you underground. We almost wish you weren’t there because you’re an impediment to our progress.’”

Grace McPhillips Lunsford, another College Park resident and board member of the city’s Main Street Program, said that’s the benefit of creating the nature preserve and outdoor classroom. No more will the river’s south metro headwaters be cast as an afterthought.

“It’s really our responsibility as stewards of the world to not only protect our headwaters but to create greenspaces that the community can be a part of,” she said.

VANISHING RIVER

Before the airport, the Flint River was a key resource shaping the development of Atlanta’s southside. As the airport grew, the Flint River disappeared from the map.

Source: Finding the Flint

About the Author

The Latest

Featured