Nine years ago, long before a new mysterious coronavirus emerged in Wuhan, China and swept across the globe, Drug Innovation Ventures at Emory set out to develop antiviral medications that could battle a broad spectrum of viruses.

They focused on inventing a drug that could tackle well-known viruses such as mosquito-borne illnesses as well as yet-to-exist, dangerous pathogens.

“It didn’t matter what might escape from a lab or what a terrorist would throw at us, or a pandemic, we knew something like this could happen,” said David Perryman, chief operating officer of Drug Innovation Ventures at Emory also known as DRIVE, which was formed by Emory University to develop early-stage drug candidates for viral diseases of global concern.

“Our goal was to be ready and have something that would work on many different viruses.”

That very drug invented here in Atlanta several years ago is now on a path to become an antiviral pill to treat COVID-19 – the first drug of its kind in the U.S. to treat the disease and a potentially major step in efforts to fight the pandemic.

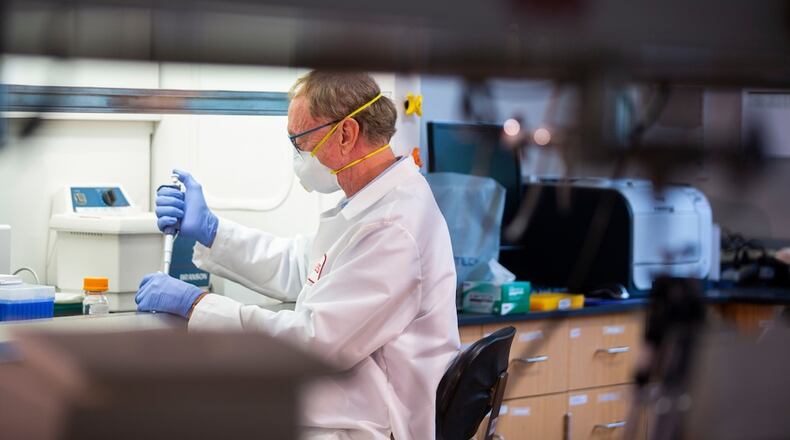

Credit: Emory (contributed

Credit: Emory (contributed

On Nov. 30, The Food and Drug Administration is scheduled to consider an emergency use authorization request for the experimental drug known as molnupiravir, which Emory’s Drug Innovation Ventures licensed to Merck pharmaceutical company through its partner Ridgeback Biotherapeutics last year.

Merck said the pill reduced hospitalizations and deaths by half in people recently infected with the coronavirus in a clinical trial when it was given within five days of when symptoms began.

The FDA will scrutinize company data on the safety and effectiveness of the drug before making a decision.

Clearance for molnupiravir could be a game-changer. A convenient pill would make it easier and faster to administer treatment on a mass scale and in a home setting. All COVID-19 therapies now authorized in the U.S. must be delivered intravenously or by injection.

There are other potential oral treatments in the wings. Pfizer recently announced that its experimental COVID-19 pill, Paxlovid, reduced hospitalizations by 89% and also prevented deaths in its own large randomized study. The company said it has also asked the FDA to authorize its antiviral pill to treat people with COVID-19 who are at high risk of becoming severely ill.

Public health experts say vaccination remains the best tool to prevent COVID-19 infection. But with millions of adults still unvaccinated — and many more globally — easy-to-use treatments will play a crucial role in curbing future waves of infections.

Convenient pill treatments could ultimately change the course of the pandemic by preventing severe sickness, keeping people out of the hospital and lowering the COVID-19 death rate.

Old drug finds a new use

Back in 2013, the main target at Emory’s DRIVE was Venezuelan equine encephalitis, a mosquito-borne illness with a high mortality rate that can affect people and horses. The Defense Threat Reduction Agency awarded Emory a $9.7 million contract to develop drugs against this disease, which had been weaponized during the Cold War.

DRIVE’s CEO and co-founder, George Painter, said the goal was always to create a drug that could attack many viruses, and over the years the drug they developed to combat equine encephalitis virus, known as EIDD-2801, also showed strong results in animal testing against coronaviruses, including SARS, and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). But SARS ultimately disappeared and MERS never became widespread.

Painter was confident the drug could have implications for emerging diseases. But there was little interest from the pharmaceutical industry — especially for a drug to fight a virus that didn’t exist yet.

That all changed in early 2020.

DRIVE first collaborated with researchers at Vanderbilt and Georgia State University for more testing. The process sped up after DRIVE licensed the drug to Merck and the pharmaceutical giant started doing human clinical trials.

Merck and its partner, Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, recently announced early results indicate patients who received the drug within five days of showing COVID-19 symptoms had about half the rate of hospitalization and deaths as patients who received a placebo pill. The study tracked 775 adults with mild to moderate COVID-19 who were considered at higher risk for severe disease due to pre-existing health problems such as obesity, diabetes or heart disease.

After nearly a month, no deaths were reported in patients who received molnupiravir, as compared to eight deaths in patients who received a placebo, according to Merck. The trial was stopped early because the interim results were so strong.

The drug works by stopping the coronavirus from replicating by inserting errors into its genetic code. When the virus tries to reproduce, it accumulates too many mutations and dies.

Because molnupiravir works by disrupting how the coronavirus replicates RNA, there could be a concern of a similar effect on human DNA or RNA. Merck reportedly has data from laboratory studies indicating that molnupiravir does not cause mutations in humans, but this will be something the FDA will be evaluating during the approval process.

Earlier this month, Britain became the first country to grant conditional authorization of the drug.

The U.S. government has committed to purchase 3.1 million doses of the drug and plans to spend $2.2 billion, according to Merck. The deal is contingent on molnupiravir receiving emergency use authorization or full approval from the FDA.

Merck also granted a royalty-free license for the drug to a United Nations-backed nonprofit in a deal that would allow the drug to be manufactured and sold cheaply in the poorest countries, where vaccines for the coronavirus are in severely short supply.

“It’s very gratifying,” said Perryman. “It has a ways to go with the FDA but when you spend 10 years of your life and many years before that to build up to that point, to be a part of something that could save lives is super gratifying.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured