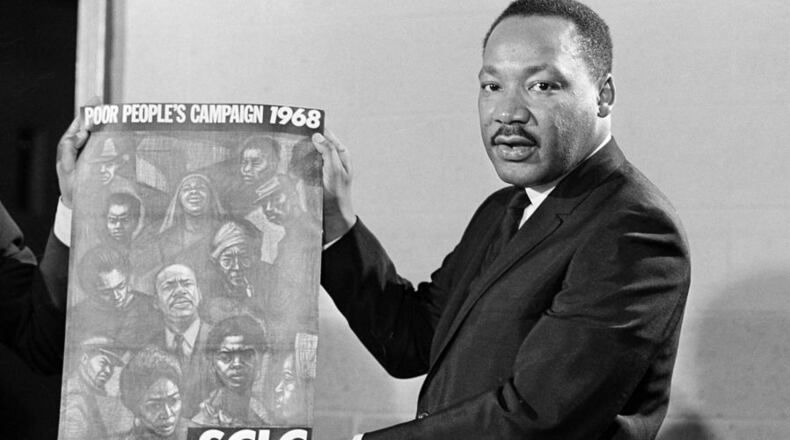

Fifty-five years ago, as he was ramping up what would become the Poor People’s Campaign, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. slammed the government’s approach to poverty, calling U.S. programs woefully inadequate.

The social safety net was too piecemeal and indirect, he argued. And poor people of all races were struggling.

“The curse of poverty has no justification in our age,” he wrote in 1967. “... The time has come for us to civilize ourselves by the total, direct and immediate abolition of poverty.”

The way to do that, he asserted, was through a government-funded guaranteed income.

King’s call for economic justice fell largely on deaf ears. But a half-century later, his hometown is planning to test the concept of guaranteed income as city leaders search for new ways to address issues like gentrification and widening income inequality.

Two guaranteed income pilot projects, including one focused on the Old Fourth Ward neighborhood of King’s childhood, are slated to launch in the months ahead. Both will give low-income participants hundreds of dollars in payments each month, no strings attached.

The philosophy undergirding the programs is not unlike that espoused by King.

Advocates say such payments can help fill in the gaps for poor families struggling to cover the cost of gas, food and other daily expenses, not to mention emergencies like a broken down car or unexpected medical bill. They believe the money can jump-start the lives of the recipients who may be buried in debt or otherwise can’t find the money to go back to school or to take days off to search for better jobs.

“Everyone deserves a decent, dignified life,” said Hope Wollensack, executive director of the Georgia Resilience and Opportunity Fund, the nonprofit overseeing the Old Fourth Ward project. “A lot of our current social policy really does not honor people’s humanity.”

Supporters hope such programs can eventually be expanded nationally, adding another poverty reduction strategy to the social safety net. Initial results in other American cities have been promising, but the experiments are so new that there aren’t yet long-term results.

The underlying concept, however, isn’t without its critics.

Some conservatives see the payments as a handout with few guardrails to prevent abuse, and many argue it could disincentivize work. Meanwhile, some researchers who study poverty abroad, where there have been longer-running guaranteed income experiments, say cash isn’t always the most effective tool for improving well-being.

“I see it as more of a Band-Aid rather than really addressing the structural issues that create poverty in the first place,” said Heath Henderson, an assistant professor of economics at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa. “It doesn’t really do much to improve health care or educational institutions or end race or gender-based discrimination.”

Guaranteed income is different from the universal basic income idea pushed by 2020 presidential contender Andrew Yang. That would allocate money to everyone. Guaranteed income is meant to be more targeted.

The concepts aren’t new.

The 18th century philosopher Thomas Paine floated providing lump sums to young people. Two centuries later, economist Milton Friedman proposed simplifying America’s patchwork welfare system with what he described as a “negative income tax.”

After Congress cleared civil and voting rights legislation, King embraced guaranteed income as the next frontier of the civil rights movement. He believed it could eradicate poverty for Black and white people alike.

“King believed that a guaranteed income was central to the dignity of the individual,” said Kelisha B. Graves, chief research, education and programs officer at the King Center.

In recent years, several European countries, including Finland and Germany, have rolled out test programs. And charities have funded major experiments in developing countries like Namibia, Kenya and India.

Several American cities have also launched privately-funded pilot projects of their own.

The most well-publicized took place in Stockton, Calif., where 125 residents were given $500 a month for two years beginning in 2019.

Participants were more than twice as likely to find full-time employment as nonrecipients, organizers reported. They could better manage unexpected expenses, were less anxious and depressed and saw “statistically significant improvements” in overall well-being and fatigue levels.

Stockton helped inspire the guaranteed income project launched by former Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms during her final weeks in office. The $2.5 million citywide program, which is funded largely with money from the developer of the Centennial Yards project downtown, will distribute $500 per month to 300 low-income recipients for a year.

Atlanta’s other pilot project, overseen by the Georgia Resilience and Opportunity Fund, is targeting a narrower slice of the population: Black women. Not only are they generationally disenfranchised, they are far more likely to hold jobs that have been negatively impacted by the pandemic, said Atlanta City Councilman Amir Farokhi, who launched the effort.

GRO’s $13 million pilot, which is privately funded, will be one of the largest of its kind. For two years, $850 a month will supplement the income of 650 Black women who are at or below the federal poverty line and live in the Old Fourth Ward, as well as yet to be disclosed locations in suburban Atlanta and southwest Georgia.

Organizers were heavily influenced by a Jackson, Miss., guaranteed income project that started in 2018.

In the eyes of Aisha Nyandoro, who runs the Jackson program, the problem with today’s safety net program is that participants are often required to jump through hoops to prove they are looking for work or poor enough to receive benefits. Once they’re approved, they are significantly restricted in how they can spend the benefits.

“We do not holistically trust Black women and Black mothers in this country,” said Nyandoro, who is chief executive officer of the nonprofit Springboard to Opportunities and advises GRO. “We say that we do, but our policies and the way that we design our systems counter what we may be saying with our mouths.”

Tamara Ware, a 37-year-old pre-K worker who participated in the Jackson pilot, said the money helped keep her family afloat after she caught COVID-19 and needed more than a month to recover.

Even more important, the mother of three said, the program allowed her to change her mindset about what was possible in her own life. She saved for the first time in years. And she dared to dream about leaving public housing for a home of her own.

Last month, Ware and her daughters moved into a townhome. In about a year she could become eligible to buy it.

Henderson, the Drake University professor, said studies of programs abroad show that guaranteed income can improve food security, nutrition outcomes and accumulation of assets in the short term. “But, in the longer term, the effects seem to dissipate to some extent,” he said.

Some people living in poverty need things beyond cash to meaningfully improve their lives, like mental health care or a substance abuse program, he said.

“If you’re really thinking deeply about what well-being is and what we’re trying to accomplish with a program like this, there are going to be things that money simply can’t buy,” said Henderson.

Credit: JOEY IVANSCO / AJC

Credit: JOEY IVANSCO / AJC

Kyle Wingfield, who heads the right-leaning Georgia Public Policy Foundation, said guaranteed income programs, if operated on a large scale, could lead to inflation.

“I think a far better way to address the concerns that are cited for programs like this is to try to make some of these (current) welfare programs work better,” he told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution late last year.

What remains to be seen is whether such a program can make a meaningful difference in Georgia.

In Old Fourth Ward, where King grew up, the neighborhood has seen seismic shifts in recent years. Major developments like the Beltline and Ponce City Market have transformed the neighborhood, causing home prices to skyrocket.

Around the time of King’s assassination, the neighborhood’s residents were 93% Black and largely working class. The median household income in 1970 was about $20,000 in today’s dollars when adjusted for inflation.

In 2019, the same area was 41% Black and the median income about $64,000, according to an Atlanta Regional Commission analysis of U.S. Census data. Median household income for Black families in Old Fourth Ward that year was less than one-third that of white families.

Kathryn Flowers, who has lived in the neighborhood for more than 20 years, said a guaranteed income program could help many. But she questioned whether it would provide a long-term fix.

“Our elected officials need to hunker down and approach issues in a more thoughtful manner that support temporary and long-term solutions to problems,” she said.

But David Mitchell, executive director of the Atlanta Preservation Center, said the programs could help keep longtime residents in place, which could make a difference when it comes to maintaining the character and legacy of a historic neighborhood like Old Fourth Ward.

“Preservation is not always just walls,” he said.

Staff writer Ernie Suggs contributed to this article.

CURRENT POVERTY RATES

City of Atlanta (2021): 20.8%

Georgia (2021): 14%

U.S. (2020): 11%

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured