Over the course of his career as an Atlanta police officer, Claude Mundy Jr. battled both crime and racism.

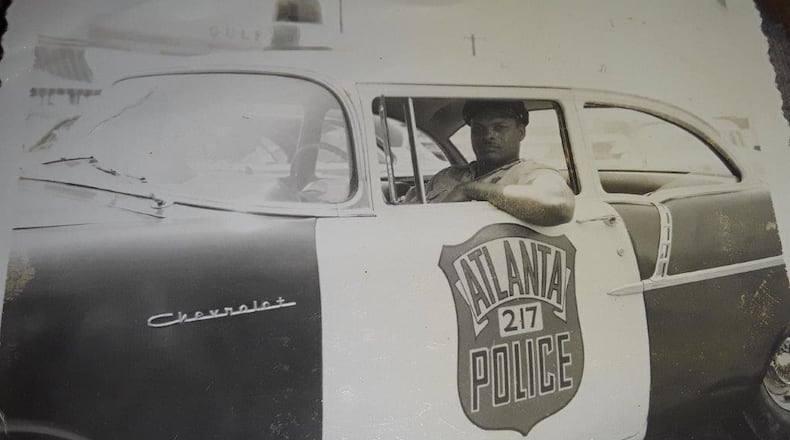

When he joined the Atlanta Police Department as a 30-year-old in the summer of 1950, segregation was in full force. The city’s first eight Black officers had been sworn in two years earlier, and Mundy was in APD’s second class of African American recruits.

He wasn’t allowed to get dressed alongside his white colleagues. Instead, Black officers had to change into uniform at the Butler Street YMCA before reporting for the start of each shift. They were discouraged from arresting white people and were assigned to patrol Black neighborhoods, where they had to walk their beats.

Credit: Atlanta Police Department

Credit: Atlanta Police Department

That didn’t deter Mundy from signing up. The no-nonsense father of five had worked in a coal yard and driven a truck, but he jumped at the opportunity to become a police officer and protect his community. He quickly excelled on the force, training hard, constantly lifting weights and eventually racking up more arrests than his white counterparts.

He dealt with racism just about every time he put on his uniform, Mundy’s grandson Dante Woods said recently. But he never took any guff from the white supervisors and colleagues who tried to belittle him because of the color of his skin.

Mundy was shot and killed on Jan. 5, 1961, while arresting a burglary suspect inside a two-story apartment building in Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward. That tragedy made him Atlanta’s first Black officer killed in the line of duty. He was 40 years old.

With a bullet lodged in his heart, Mundy pulled out his service revolver and emptied it into Joe Louis Pass, the 25-year-old who shot him. Both he and Pass, who was also Black, died on the way to the hospital.

“He wasn’t a man to fool with,” Mundy’s former colleague Ernest Lyons told The Atlanta Constitution in 1992. One of the city’s first Black officers hired in 1948, Lyons retired as a sergeant after 32 years on the force. “I had to restrain him a few times” when people used racial slurs, he said regarding Mundy.

Credit: AJC Archive at GSU Library

Credit: AJC Archive at GSU Library

The late Howard Baugh, who broke through racial barriers to become APD’s first Black detective and first Black commanding officer, recalled the time a white lieutenant disparaged the African American officers at roll call.

Officer Mundy, he said, raised his hand and declared, “I’d like to whup your (butt).”

The lieutenant declined the challenge but assigned Mundy to Decatur Street — a punishment beat where officers walked a lot and did little else.

“Mundy made 30 arrests the first week and even cited a train engineer for blocking a street for more than 10 minutes,” Baugh told the newspaper nearly three decades ago. “He worked hard, no matter where he was.”

Credit: Atlanta Police Department

Credit: Atlanta Police Department

On the street, his reputation preceded him.

“He’d drive up to a corner, even when he wasn’t working, and people would leave,” Mundy’s widow, Vivian Lewis, said in the early 1990s. “Too bad they don’t have that control and respect now.”

Mundy was also one of the first Black officers — if not the first — to arrest a white man in Atlanta. (It wasn’t exactly a milestone that would’ve been celebrated at the time, and some of the details of that arrest have been lost to history.)

One afternoon, he cuffed a white man and hauled him to the jail, his daughter Marilyn Mundy-Woods told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. The youngest of his children, she was 5 when her father was killed.

Credit: Family Photo

Credit: Family Photo

“He did end up arresting a white guy, and in the process two white officers came up and asked, ‘What do you think you’re doing? You know you can’t arrest anybody white,’” Mundy-Woods said. “Dad looked at them and he said, ‘Well who’s gonna stop me?’” The men stepped aside and he completed the arrest.

Mundy’s contemporaries said the department’s white officers warmed up to them after Mundy’s line-of-duty death, which occurred just days before the first attempt to integrate the University of Georgia.

“Before, it was like we were infringing, we were getting something we hadn’t earned,” Baugh said. “But when he shed his blood, it was like: They’re here; they’re ready. A lot of bitterness ceased that day.”

Credit: Family Photo

Credit: Family Photo

As a tribute to their fallen comrade, Mundy’s fellow Black officers had his .38 caliber revolver gold-plated following his death. The gun ended up on display at the now-closed Kennedy Community Center before being stolen in the summer of 1990 and used in a weekslong crime spree at motels across metro Atlanta. One of the victims, an Alabama man in town visiting Six Flags, was fatally shot during a robbery in Douglasville.

“Imagine how we felt when we got the call that the ‘golden gun’ we’d heard about on TV was his,” Mundy’s grandson said.

Last month, Mundy’s family and the department’s top brass gathered at the officer’s northwest Atlanta gravesite to commemorate his sacrifice six decades after his death. Among those in attendance were Mundy’s two surviving children, most of his eight grandchildren, and some of his 23 great-grandkids.

Credit: Shaddi Abusaid / shaddi.abusaid@ajc.com

Credit: Shaddi Abusaid / shaddi.abusaid@ajc.com

Interim APD Chief Rodney Bryant said it was important to recognize the officer’s service to the city and the department.

“His memory and his efforts back then continue to bring us forward, even to this day,” Bryant said, acknowledging that it has never been easy to be a cop, let alone an African American officer during segregation. “We’re no longer looking at firsts because of him.”

Today, Bryant said, Atlanta’s police force is nearly 60% Black, much more reflective of the communities it serves.

Atlanta Councilman Michael Julian Bond commemorated the anniversary of Mundy’s death by reading a proclamation from the city and presenting it to the slain officer’s family.

Bond, the son of the late civil rights activist Julian Bond, said Mundy was killed at the height of Atlanta’s student movement to desegregate the city. At the time, he was tasked with defending people who “wouldn’t share a sandwich with him, wouldn’t even sit next to him.”

Bond said he couldn’t begin to imagine the abuse Atlanta’s first Black officers must have endured as they patrolled city streets — getting spat on or called the n-word by some of the very residents they took an oath to protect.

“As the city’s first African American police officer to lose his life, this is a recognition that’s way overdue,” Bond said. “Despite the controversies that embroil this profession, these men and women get up every day and they put their lives on the line. Officer Mundy paid the ultimate price and we don’t want his name to be forgotten.”

BLACK HISTORY MONTH

Throughout February, we’ll spotlight different African American pioneers ― through new stories and our archive collection ― in our Living and Metro sections Monday through Sunday. Go to AJC.com/black-history-month for more subscriber exclusives on people, places and organizations that have changed the world, and to see videos on the African American pioneers featured here each day.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured