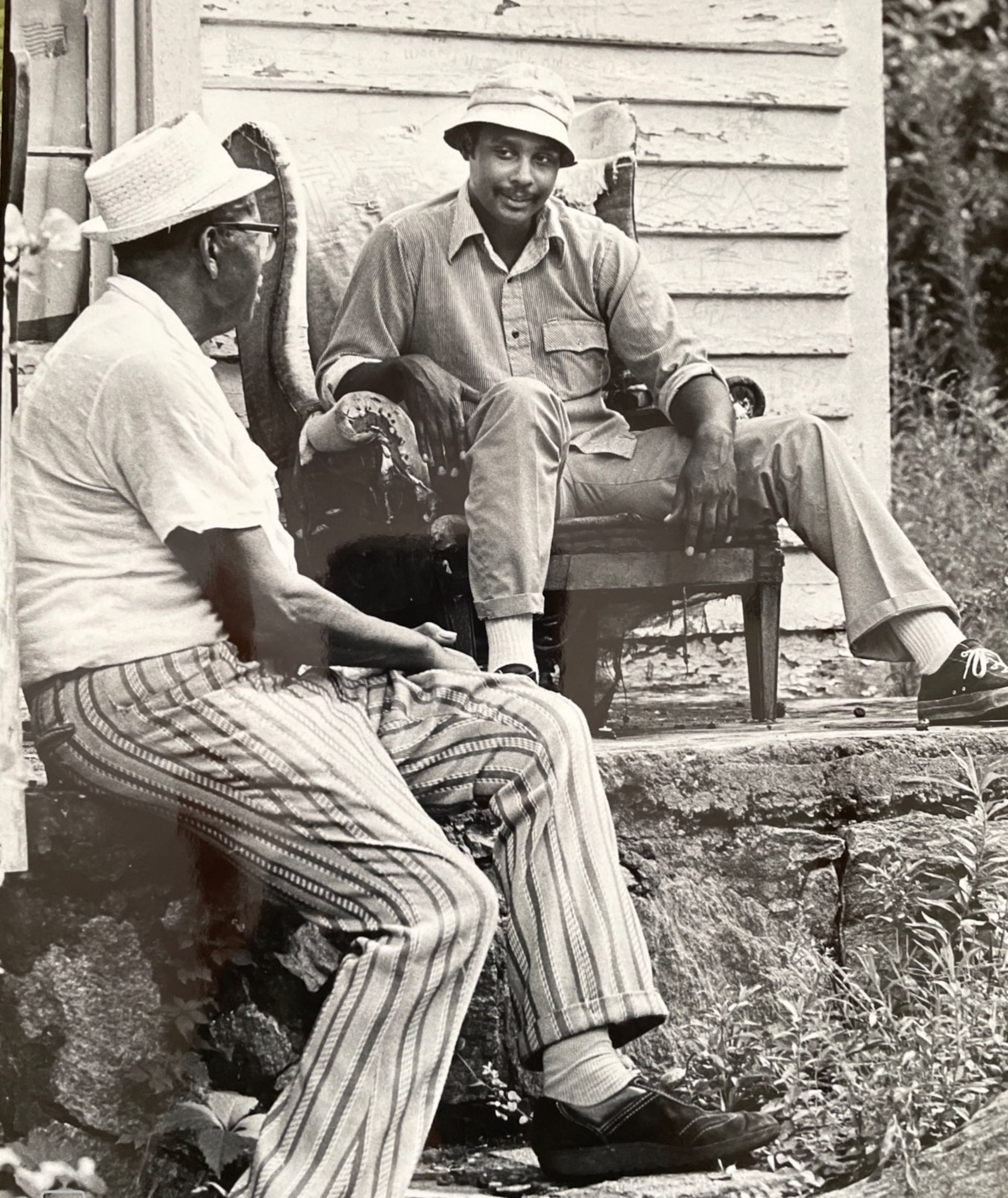

Chet Fuller, pioneering Black journalist in Atlanta, dies at 72

Chet Fuller wasn’t supposed to come back home to Atlanta, but history pulled him.

A 1972 magna cum laude graduate of Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota, he had been accepted to Yale University with the intention of getting a Master of Fine Arts in playwriting.

He had already won an award presented by Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks for his collection of poems, “Spend Sad Sundays Singing Songs to Sassy Sisters.”

But in the summer of 1972, he accepted a position writing sports stories for the Atlanta Journal.

“He wanted to come back to Atlanta so he could get a job making real money before we moved to New Haven,” said Fuller’s wife, Pearl Seabrooks Fuller.

He spent the summer working with well-known writers and editors Lewis Grizzard and Furman Bisher. By fall, they had convinced him to stay.

“He was going to become a playwright, but he turned it down,” Seabrooks Fuller said. “He second-guessed himself a lot about it. But he decided that he would stay and work full time that fall. He wanted to be here and work in the city.”

Fuller became one of the first Black journalists to work at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, following Harmon Perry, who in 1968, became the first Black reporter for the then-separate Atlanta Journal.

“At times, we walked on eggshells, because there were not many Blacks on the journalism staff,” said Pete Scott, who came to the paper in 1971. “We would often talk about being black and the contributions we were making. We knew how important it was, not only for us, but for those who were coming after us.”

Chester Fuller Jr., who worked for the paper for 26 years before retiring in 1998, died Aug. 2, 2022.

Mrs. Fuller said he had a heart attack. He was 72.

A memorial service will be announced later.

A “Grady baby,” Fuller was born March 1, 1950, in Atlanta.

His mother, Roberta Jester Fuller, was a domestic worker, and his father, Chester Lee Fuller, was a day laborer.

Fuller grew up in the Summerhill neighborhood of Atlanta and starred as a football and baseball player at Luther Judson Price High School, where he graduated in 1968. Forgoing athletic scholarship offers from local colleges, Fuller accepted an academic scholarship to Gustavus Adolphus College.

Seabrooks Fuller, who at the time was a sophomore at Gustavus Adolphus College, spotted him at the airport in St. Peter as both arrived for the fall semester.

Moments later, she was surprised to see that he had been assigned to ride in the same limo to campus. The limo driver tried to lift Seabrook Fuller’s suitcase, but it was too heavy.

“I said ‘This boy was gonna help me.’ And (Chet) said, ‘Where do you see a boy?’” Mrs. Fuller recalled. “He was so brash, young and cocky.”

Having met in September of 1968, they started dating and got married on May 9, 1969.

After his summer in sports at the AJC, Fuller asked to join the news team because he felt he could make more of an impact.

He helped cover Wayne Williams and the Atlanta Child Murders and the mayoral tenures of Maynard Jackson and Andrew Young. He became assistant city editor in 1978.

He won journalism’s Green Eyeshade Award in 1979 for “A Black Man’s Diary,” a 10-part series based on three months of traveling the South as an unemployed Black man looking for work. In 1981, his reporting was turned into the book, “I Hear Them Calling My Name.”

Fuller became an editorial writer and columnist in 1983 and assistant managing editor in 1989. He helped usher in a new generation of Black journalists and also wrote a weekly column called Urban Spotlight.

Fuller retired from the paper in 1998, but not from journalism.

Alexis Scott, who was an AJC reporter with Fuller and later a vice president of community affairs at Cox, had left the company to manage her family’s newspaper, The Atlanta Daily World.

She needed a managing editor and called Fuller.

“He came to help me out because we were drowning. He was cynical, as most great journalists are, but he was really amazing,” she said. “Our staff was pretty inexperienced, so he would work really hard with those kids who were trying to get their breaks in journalism. He was here 24/7.”

In 2006, Fuller became the editor of the Clayton News Daily and the Henry Daily Herald. His final retirement came in 2012.

Since at least 2015, Fuller continued writing in his Straight Up blog about national and world events, society and the arts. His last column, published on July 5, took on the current state of American politics.

“Unfortunately, we have scores of political candidates these days — newcomers and veteran pols alike — running for offices on seemingly every level of government, whose motives — to put it bluntly — are dangerous, and sometimes, deadly,” he wrote. “Through lies they know are lies, misdirection and made-up scenarios, they create dangerous divisions in their communities, dividing the populace by race, ethnicity, religious beliefs and cultural practices into warring camps that distrust one another, sometimes, to the point of outright hatred and rage that — more and more lately, lead to unnecessary violence.”

Aside from his wife, Fuller is survived by his brother, Gregory of Decatur; three daughters, Njeri Fuller Boss, Edde Fuller Sommer and Obia Fuller; and six grandchildren.