On Thursday, 116 years ago, a mob of white residents began a four-day offensive through Atlanta’s Black business district and elite neighborhoods, destroying nearly everything in sight.

By the time the violence and bloodshed ended, an estimated 25 Black people were killed.

Immediately, local and even international media outlets dubbed the event a “riot.” Over the last century, scholars have referred to it formally as “The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot.”

Today, on the heels of the 2020 deaths of Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks and George Floyd, and renewed interest in the history of racial violence, a growing number of local historians and civil rights advocates are trying to shift the narrative surrounding the events by renaming it “The 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre.”

The Coalition to Remember the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre will place three markers at key spots from the massacre this weekend. “It is to pay homage, as well as to set the correction in history around what happened,” said Ann Hill Bond, co-chair of the Fulton County Remembrance Coalition.

They are following groups in Tulsa, who successfully lobbied in recent years to change the reference of the 1921 “Tulsa Race Riot” to the “Tulsa Massacre” and the 1898 “Wilmington Riot” to the “Wilmington Massacre and Coup d’état.”

On each occasion, advocates argue that the new names offer a clearer definition of what actually happened.

“The name is misleading and this is history that is not largely known,” said Jill Savitt, CEO of Atlanta’s National Center for Civil and Human Rights. “With ‘riot’ there is a context where it sounds like the Black community was rising up and committing the violence. This was not an attack by the Black community. It was an attack on the Black community.”

Credit: Natrice Miller / Natrice.Miller@ajc.com

Credit: Natrice Miller / Natrice.Miller@ajc.com

On Wednesday, Congresswoman Nikema Williams (D-Atlanta) introduced a resolution in U.S. Congress, “Condemning the atrocities that occurred in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1906, in which White supremacist mobs brutalized, terrorized, and killed dozens of Black Americans, and reaffirming the commitment of the House of Representatives to combating hatred, injustice, and White supremacy.”

Sen. Jon Ossoff (D-GA) introduced a companion resolution Wednesday in the U.S. Senate.

Last weekend, at a series of dinners across the city, the National Center for Civil and Human Rights and the Coalition to Remember the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre launched a petition to replace “Riot” with “Massacre.”

Over the last year, the Georgia Historical Society and the Atlanta History Center have adopted the new wording.

Sheffield Hale, president of the Atlanta History Center, said all references to riot throughout the museum and online have been scrubbed in favor of massacre.

Credit: CURTIS COMPTON / AJC

Credit: CURTIS COMPTON / AJC

“It makes sense,” Hale said. “Massacre is a better descriptor than race riot. It was really a one-way riot. This is something that was imposed on the Black community and we want to reflect that.”

WABE, an NPR affiliate based in Atlanta, moved last week to change the name in its future coverage.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution does not have a formal policy. But last year, in an article on the 115th anniversary of the attacks, it referred to the violence as both a riot and “The 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre.”

Hannibal B. Johnson, an attorney and author in Tulsa, agrees with the shifting language.

In the years leading up to the centennial anniversary of the 1921 Tulsa racial attacks, where close to 40 Black people were killed and the so-called Black Wall Street was burned down, Johnson said a Black coalition of voices started talking about change.

“They felt the word ‘riot’ was soft and not an accurate descriptor of what happened,” said Johnson, who wrote “Black Wall Street 100 — An American City Grapples With Its Historical Racial Trauma.”

“I often ask, ‘Who named the event?’ ‘Why was the name chosen?’ ‘Who was absent from the table when the name came down?’ ‘What alternatives?’ And ‘What would you choose?’” Johnson said. “It forces people to think.”

In simple terms, a massacre is described in Merriam-Webster as “the violent and cruel killing of a large number of people.” A riot is defined as “a tumultuous disturbance of the public peace.”

The 1906 violence in Atlanta started at least partly because of a perceived threat to white gentility against the backdrop of Black progress, according to many scholars.

Credit: Unknown

Credit: Unknown

In Post-Reconstruction, Atlanta’s Black middle class was emerging in large part because of the establishment of businesses, churches and the Black colleges Atlanta University, Clark College, Morehouse College, Spelman College, Morris Brown College and Gammon.

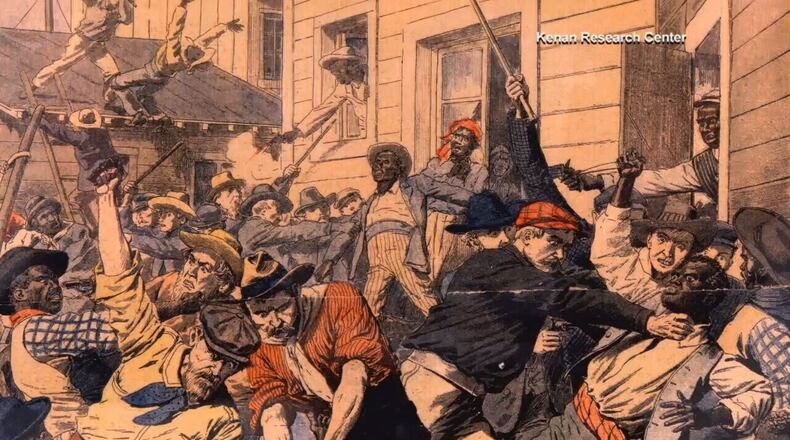

But on the morning of Sept. 22, 1906, several local newspapers reported four alleged sexual assaults on local white women by Black men. Local gangs and mobs of white men prowled the streets of Atlanta looking for businesses and homes to destroy and Black people to maim and kill.

The riot began near Five Points and spread throughout downtown and into the Brownsville neighborhood in South Atlanta as thousands inflamed by sensational and inaccurate newspaper reports — in both the Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution — started attacking Black residents at random.

Over four days, an estimated 25 Black people were killed, although several accounts put the number higher. They were shot, stabbed or beaten to death. Bodies were dumped at the foot of the Henry Grady statue. Men were thrown out of the windows of the old Kimball Hotel. Some were said to be hung from light poles.

Credit: Rich Addicks

Credit: Rich Addicks

Two white people also lay dead. No one was ever convicted of rioting or murder.

Although it happened 15 years before the Tulsa Massacre, the Atlanta events went largely forgotten.

In 2001, former Emory University professor Mark Bauerlein’s “Negrophobia: A Race Riot in Atlanta,” helped bring attention to the tragic events. In 2009, journalist Rebecca Burns followed with “Rage in the Gate City: The Story of the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot.”

Bauerlein, who retired in 2020, said he always accepted the word riot because it was what came up in the books and articles that he used in his research.

“I heard the word riot so often it didn’t serve as a problem. I didn’t reconsider it until last year,” Bauerlein said. “I am a person that adheres to traditions and thinks that changes should be done judiciously. But I think in this instance, it is a fair case.”

In Tulsa, Johnson said the way the people refer to the event has changed, although the word riot will continue to appear in historical documents.

“But in the present, most people use the word massacre,” he said. “They are empowered by the language.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured