The ongoing saga surrounding jail space in Atlanta reached a new chapter Monday as city officials announced an agreement to lease hundreds of beds in its mostly empty detention center to Fulton County for the next four years.

An ordinance introduced by Councilman Michael Julian Bond would allow Fulton County to house up to 700 inmates at the Atlanta City Detention Center for four years. The county would pay $50 per day for each person housed at the city’s facility, with the city also entitled to 65% of the phone and commissary fees generated there.

But once that agreement is up, Mayor Andre Dickens said Monday, he wants the 11-story building on Peachtree Street to be fully repurposed — a move activists have sought for years.

Fulton County Sheriff Patrick Labat has been trying to lease space at the city’s detention center since the first week he took office in 2021.

The agreement, which is subject to approval by the Atlanta City Council and Fulton County Commission, follows concerns about overcrowding at the county’s jail, and simultaneous calls from local activists to close the city’s detention center, which holds fewer than 50 detainees a night. Most are held on minor, nonviolent offenses.

Dickens said in a statement that he remains “committed to fully repurposing the (detention center) facility for non-incarceration purposes.”

“But we are also confronted by a real and immediate crisis of overcrowding at the Fulton County Jail,” the mayor’s statement continued. “This temporary lease agreement will allow the City of Atlanta to play a role in alleviating this humanitarian crisis and provide the time necessary for Fulton County to develop and implement a long-term solution.”

Of the 700 detainees, about 250 will come from the county’s Union City facility and the other 450 will come from the Rice Street facility and others, the city said.

The mayor’s office said that plans to open a diversion center in its facility by 2023 are still active, and that the city will seek proposals for “alternative uses of the building at the end of the lease agreement with Fulton County.”

Tension between the city and county over the jail heightened last year, during the end of former Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms’ term. She pushed for the closure of the city’s detention center after a task force recommended it be demolished and replaced with a community center. She was open to leasing some space to the county and offering a re-entry program, but those negotiations fell through.

Credit: AJC File

Credit: AJC File

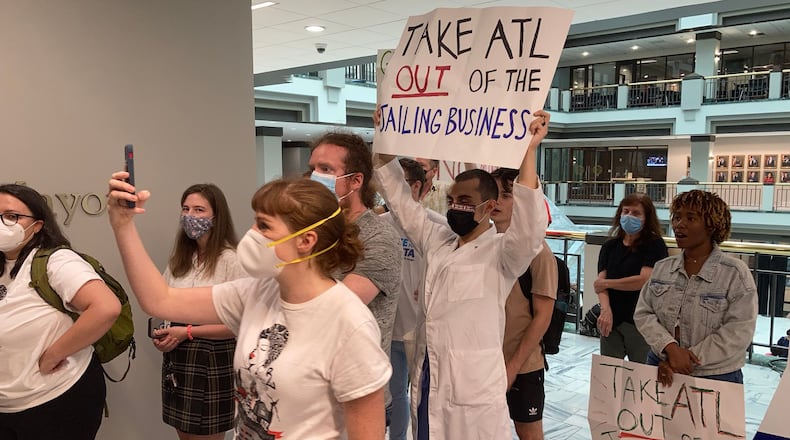

Since Dickens took office, activists have continued to push the city to follow through on Bottoms’ goal of closing the detention center. About 20 protestors stood outside the mayor’s office at City Hall on Monday and called for Dickens to meet with them.

“Keep your word, Dre,” the group chanted, their words echoing through the large City Hall atrium. “Open the door so we can close the jail.”

The protesters said news of the lease agreement was disappointing, especially since Dickens supported a 2019 resolution in support of creating a task force to make suggestions for ending the facility’s role of housing inmates.

The Communities Over Cages Alliance, a coalition of over 40 Atlanta organizations pushing for the closure of the jail, quickly denounced the proposal, calling it a slap in the face to criminal justice reform efforts.

“The plan to repurpose ACDC was created by a wide range of community members, elected officials, and system stakeholders, and was sponsored by Mayor Dickens himself when he was a council member,” said Robyn Hasan, the executive director of Women on the Rise, a grassroots organization led by formerly incarcerated women. Why would he turn his back on his own initiative?”

In late June, three council members introduced a resolution in support of closing the detention center and turning it into a facility that provides mental health support, drug and alcohol treatment and transitional housing. The center would be named after the late Congressman John Lewis.

While that measure is on hold in a City Council committee, hundreds of inmates ― innocent until proven guilty — sleep on the floor of Fulton’s Rice Street jail every night.

Labat has sought to alleviate the overcrowding since taking office in January 2021: He signed deals with Cobb County to hold inmates and is exploring other counties with availability. Labat also worked to reopen the North Fulton jail annex and he ushered in a feasibility study for a proposed $500 million new jail.

While his department spends millions of taxpayer dollars and searches the state for more room to house inmates, the city of Atlanta’s spends about $16 million to keep open a 1,300-bed facility that sits nearly empty. The detention center is left unused in part because of a 2018 city ordinance that eliminated cash bonds, which kept many low-level offenders behind bars.

Construction of the current county jail cost taxpayers $50 million and was rushed along because of a federal lawsuit regarding overcrowding. Despite being more than six times larger than the previous jail, it immediately filled upon opening in October 1989 amid the nation’s war on drugs.

Stressed from the flow of inmates, the jail started to fall apart — walls leaked and showers backed up. By 2004, a federal judge had taken control of the jail away from Fulton. During the 11 years that the jail remained under federal oversight, Fulton taxpayers spent $1 billion bringing the jail into compliance.

Activists say the county’s track record shows that leasing Atlanta’s jail space won’t provide the relief Labat says it will.

“They’ve had an overcrowding issue since I’ve been in middle school,” local organizer Devin Barrington-Ward said. “And I’m 32 years old.”

A City Council committee is set to take up the measure next week. The Fulton County Commission’s next scheduled meeting is Wednesday at 10 a.m.

Credit: WSBTV Videos

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured