Atlanta’s leading landscape architect, 93, still drawing

The kiss of the sun for pardon,

The song of the birds for mirth,

One is nearer God’s Heart in a garden

Than anywhere else on earth.

Edward L. Daugherty, the dean of Atlanta landscape architects, has seen many cycles of growth and decay. He has survived enough seasons to view his own wintertime with a sanguine eye.

He is 93 years old and is going through chemotherapy, which would be enough to knock down the average gardener.

But after a recent dramatic visit to the ICU, he somehow bounced back, and then went back to work, answering phone calls, setting up appointments. One of those was with a client, Carter Morris, who is overseeing Sarahs’ Garden, a project at the Second Ponce de Leon Baptist Church in Buckhead.

When she didn’t answer the phone, he left a message in her voicemail: “This is Lazarus.”

The feature he’s designing for Second Ponce de Leon is a respite garden, sponsored by eight churches, for caregivers of those with dementia. He’s also drawing up plans for a restoration of a sunken park at the intersection of Peachtree Battle and Rivers Road and is in the midst of designing a garden for a private residence.

A visitor to his hospital room found him sitting up in bed, a hospital table across his lap, sketching ideas on large sheets of paper.

At 93, Daugherty does not want to quit.

Now his students, clients, friends and colleagues are evaluating the enormous impact Ed Daugherty has had on the look of Atlanta.

"He's basically touched every part of the city," said Staci Catron, director of the Cherokee Garden Library, in the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center, where Daugherty's archives are collected. "He's done everything from a window box at a little old lady's house to huge landscapes at Georgia Tech," said Catron. "In our archive, there are over a thousand sets of his landscape drawings, for a thousand projects, and that's not all of them."

It’s possible that Daugherty’s equanimity comes from a lifetime of building tranquil places. He jokes that his drive to continue working is “because I’m insane!” But he also can’t resist the chance to do some good. “When these pro-bono offers came up, I was sympathetic to the program.”

Daugherty, fresh out of the hospital, spoke recently about his 60-plus-year career while offering a tour of his home on W. Wesley, just down the street from the Peachtree intersection. It is decked out with Burford holly, cherry, laurel, and camellias, and the front yard is screened from the street by a 15-foot hedge of tea olive, sasanqua, cherry laurel, elaeagnus and Japanese holly.

He gets around with the aid of a walker, but discards it if he feels like it. Like Daugherty, the yard is not showy, but it is practical. The hedge creates a private room-like space in the front for romping children (or grandchildren) and the wisteria clinging to the pergola in back will, in season, delight the nose as well as the eyes.

Don’t look here for Daugherty’s best work, however. Look at one of the many public or private worlds he has created, including the planning for the square in Marietta, the gardens at the Governor’s Mansion and the allée of crepe myrtles at the Atlanta Botanical Garden.

In 2010 he was awarded the ASLA Medal, the highest honor for a landscape architect given by the American Society of Landscape Architects.

“People throw the word ‘genius’ around, but Ed is a genius,” said Hugh Saxon, deputy city manager in Decatur, where Daugherty has been helping to sculpt the Decatur Cemetery for more than 50 years. In Decatur, he also developed the master plan for the Woodlands Garden park and created a pocket park on Oakview Road.

He’s spent so much time in the cemetery that he celebrated his 85th birthday there.

Atlanta is the most shape-shifting of Eastern cities, where buildings come and go like erasable words on a whiteboard. Neither are gardens or trees any more permanent. (One of Daugherty’s rose gardens at the Atlanta Botanical Garden was obliterated, regretfully, by the pencil of one of Daugherty’s students.)

Where Daugherty has left his mark is in the minds of other landscape architects and gardeners, and in the feelings of visitors who have walked in his environments. "His legacy is not just landscapes," said Charles Birnbaum, founder president and CEO of the Washington, D.C.-based Cultural Landscape Foundation, "but multi-generations of Atlantans who have come to appreciate the science and art of landscape architecture. He really is sort of a poet and a pied piper; he's bringing everyone along."

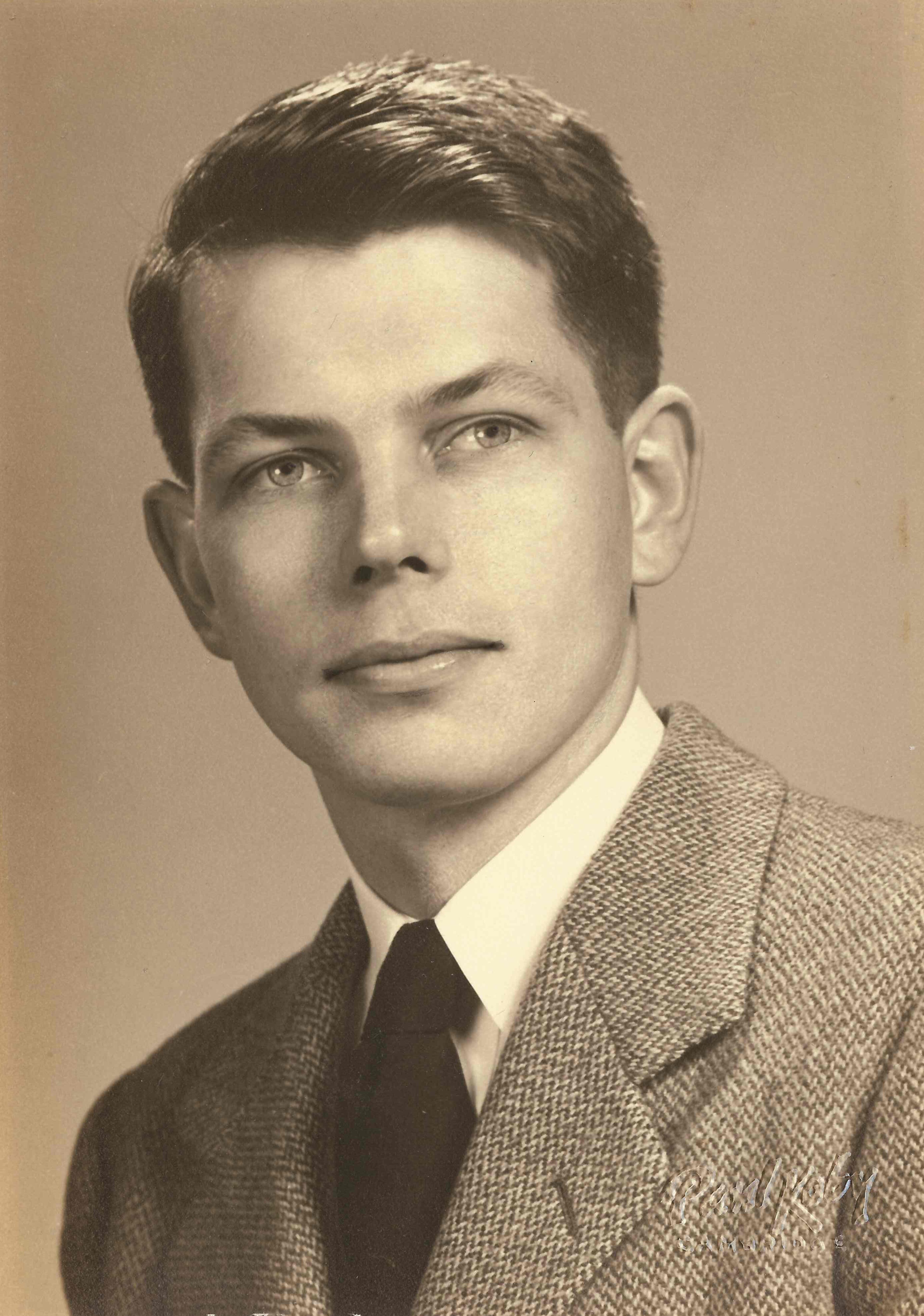

A youngster in a young city

Born in Summerville, South Carolina, Daugherty grew up at 1345 West Peachtree, midway between Lombardy Way and 17th Street. As a young boy, he reveled in the contrast between his mother’s well-ordered garden and a four-acre “wilderness” that he walked through on the way to school. (This was the era when 5-year-olds were allowed to walk to school on their own.)

“There was a little stream,” he remembers. “There were frogs, snakes and tadpoles. Occasionally a drunk asleep in the woods.”

Once inside the woods, you couldn’t see the borders of it, which is what made that small copse magical: the sense that it was infinite.

Young Ed indulged in the sort of mischief available to children of the Depression, flipping goldfish out of his mother’s pond and soaping the streetcar tracks. He delivered the Ladies Home Journal and the Saturday Evening Post to Midtown customers, including Margaret Mitchell, who lived nearby. He graduated from North Fulton at age 16 because the county only offered three years of high school.

As a freshman at Georgia Tech, he studied architecture, but it seemed that the students there created buildings with no connection to their surroundings. “This bothered me,” he said in an oral history, “because it often looked like they didn’t belong on the land, or it was an unhappy, uneasy relationship.”

(While still a teenager, he earned spending money as a ballroom dance instructor at the studios of Margaret Bryan — herself a protege of Arthur Murray. He still maintained sharp swing dance skills into his ninth decade, demonstrating fluid footwork at a mountain community talent show a few years ago.)

After returning from stateside service in the Army, Daugherty studied the young discipline of landscape architecture at the University of Georgia, hoping to become a better architect. His professor encouraged him to apply to Harvard, where he studied in a department led by Walter Gropius. He won a Fulbright Scholarship to study in England, where the government nationalized efforts to rebuild housing in the bombed-out landscapes still reeling from the German blitz. This helped form a coherent plan for development, including parks and greenbelts.

Back in the U.S.A. he hoped the same approach would take root here. It didn't. "Planning commissions in Atlanta kept putting forth plans for green belts, greenswards and regional parks, but they were constantly shot down by opportunists who obviously had good reason to want to maximize their investment," he told Charles Birnbaum at the Cultural Landscape Foundation.

Most of the action in Atlanta’s big firms involved designing subdivisions and shopping centers, which did not interest Daugherty. Instead, he went into business for himself, setting up a drafting table on the sleeping porch at his parents’ house.

What is landscape architecture?

His first challenge was explaining to potential customers what landscape architects do.

Don Hooten, who worked in Daugherty's firm for eight years, said those in his discipline deal not only with plants, but with questions of engineering. They handle "the bones of the garden, the hard elements: The walks, the walls, the technical aspects of it, like grading and draining," he said. "We had an education in school, but working with Ed was the education."

Daugherty taught a respect for the use of native plants long before that became common practice, “because they know how to behave.” He also stressed a practical approach to using trees.

Spencer Tunnel, a former employee, now an established landscape architect, recalled this exchange:

“I’d draw plans. He’d say, ‘Where are the power lines?’ I’d say ‘I don’t know.’ He’d say ‘You need to know because as soon as these trees get planted, Georgia Power is going to come in and castrate them. Save the client money.’”

Whether he was designing public spaces, or private gardens for such clients as mayor Ivan Allen, photographer Lucinda Bunnen and architect John Portman, Daugherty said he had to address fundamental issues. What is this space for? How will it be used?

Homeowners with children often have airy plans for ornamentals that will certainly be trampled.

“You had to ask questions,” said Daugherty. “Are you going to grow dahlias or children? Some people said ‘I want a tennis court.’ Or a swimming pool. But a tennis court needs 60 feet by 120 feet. That’s almost an R-4A lot.”

Daugherty himself and wife Martha raised four children -- and perhaps a few dahlias. Daughter Harriet Daugherty said “He taught us by example, how to curse in Latin plant names, how yard work can feed the soul, and, how like a garden, like the land, we all need care and tending.”

Early in his career, Daugherty was tapped to help redesign the hilltop heart of the Georgia Tech campus, which had cars “jammed right up under the windowsills,” he said. “We used to refer to it as the world’s only concrete campus.” He introduced walkways, plantings, open space, and moved the cars to the side.

Later Daugherty taught landscape architecture at Tech. Though only four undergraduates subscribed to his class that first year (his classes drew 40 or more by the time he finished, 10 years later) the Daugherty gospel took seed in many students.

One thing they learned was the sensual pleasure of good design.

Daugherty often took his students to Ansley Park to peer down into Yonah Park, one of the landscaped ravines that ornament the Midtown neighborhood. Ansley was created by Solon Zachary Ruff, a protege of Frederick Law Olmsted (the co-designer of New York’s Central Park), and when Daugherty describes the brilliance of Ruff’s designs, it verges on the rhapsodic.

“You can stand at the edge and peer over into this space, and have the vertiginous sense of deepness,” he says. “And then you can walk down into it and have it wrap around you like a fur coat, and be completely enclosed and see the city disappear.”

More Stories

The Latest