‘Written by himself’: How slave narratives shaped modern Black literature

There is a moment in Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel “Invisible Man,” when the narrator arrives in New York City and is amazed by what he perceives as the unlimited freedom enjoyed by the city’s Black people.

But having “escaped” from the South, a painful reality sets in when he discovers the North presents the same barriers to Black achievement as the South.

“He doesn’t know what freedom means until, gradually, he gets to the point where he is disillusioned and tries to recover who he is,” said William L. Andrews, the E. Maynard Adams distinguished professor of English, emeritus at the University of North Carolina.

Although Ellison’s work is a novel, its structure, themes, and motifs are straight out of an earlier generation of Black literature - slave narratives, the foundation upon which subsequent Black artistic forms are based.

Writers like Ellison, Richard Wright, Alex Haley, Toni Morrison and Colson Whitehead took cues from former slaves turned authors like Frederick Douglass, Olaudah Equiano, Harriet Jacobs and Mary Prince in creating works that built on those traditions.

“Every literary form that Black people have produced in the Americas descends from slave narratives,” said Joycelyn Moody, the Sue E. Denman Distinguished Chair in American Literature at the University of Texas-San Antonio. “In my library, I am surrounded by many books. They are all on Black literature and art. And all of it derives from slave narratives.”

Although Black expressive art has always existed through songs, hymns and poetry, nothing was as expansive as the genre of slave narratives.

“No other group of slaves anywhere, at any other period in history, has left such a large repository of testimony about the horror of becoming the legal property of another human being,” wrote scholar Henry Louis moody in the introduction to his “The Classic Slave Narratives.”

Spanning from the mid-18th century until the Great Depression, researcher Marion Wilson Starling, in 1946, estimated that more than 6,000 forms of personal slave accounts — ranging from broadsides, criminal confessions, courthouse records and oral histories—are believed to exist.

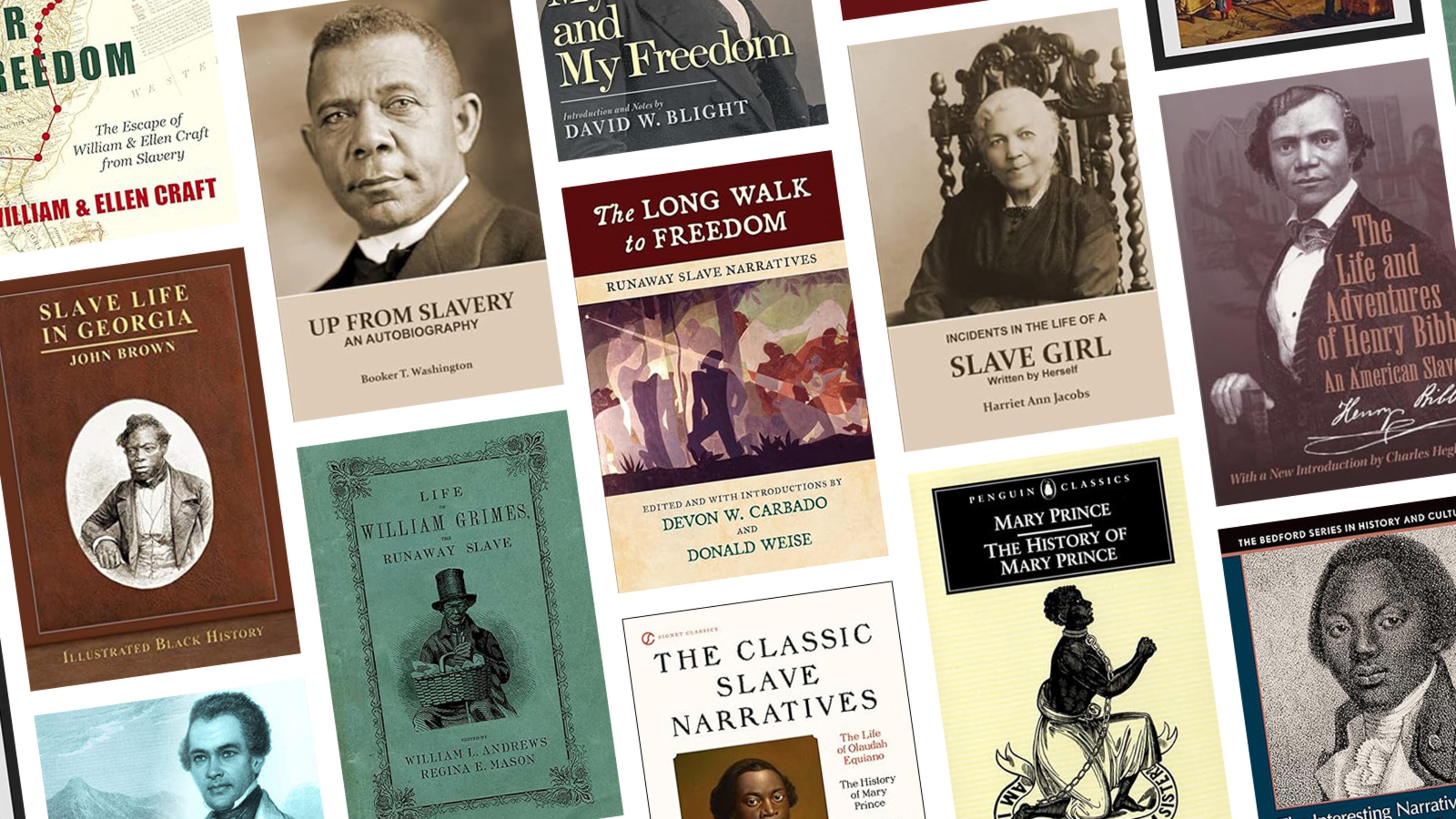

Andrews, the general editor for DocSouth’s “North American Slave Narratives” project out of the University of North Carolina, said there are more than 200 book-length slave narratives. They are autobiographical texts, written in English by slaves or former slaves who had to have direct input in the writing, either by holding the pen or dictating it. All are accessible through the website.

Roughly half of them were written, with the help of sympathetic whites, before 1865 and they all tell the story of the cruelties of “the peculiar institution” in an attempt to indict the system while exposing it.

I was born...

Many of the books start with a simple opening line, “I was born.”

It immediately establishes the former slave’s earliest account of his or her existence, followed by an account of their parentage, a description of their abuse by a cruel master, a spiritual awakening and their triumphant escape or emancipation.

The titles of the books were often long and descriptive with the tagline, “Written by Himself,” like: “A Narrative of Some Remarkable Incidents in the Life of Solomon Bayley, Formerly a Slave in the State of Delaware, North America; Written by Himself, and Published for His Benefit; to Which Are Prefixed, a Few Remarks by Robert Hurnard (1825).

The distinctive “I was born...” opening sentences and the taglines were intended to counter a suspicion that former slaves did not write their autobiographies. Instead, plenty of whites, especially in the South, claimed the narratives were concocted by white abolitionists pushing an anti-slavery agenda.

The “Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave, Written by Himself (1825),” was not only written by William Grimes, but he paid for it to be published and peddled it in New Haven, Connecticut, where he had settled after escaping. The details about slavery and the cruelties of slaveholders that Grimes revealed were more hard-hitting than even what white abolitionists of his time were willing to write, Andrews said.

“Racist myths in the 19th century argued that Black people were not intellectually capable of writing these stories. But many have had remarkable staying power and the vast majority have been proven by scholars to have been true,” Andrews stressed. “Did some slave narratives have white editors? Yes. Were a few ghostwritten? Yes. But that doesn’t mean that they are false. Even though most of the narrators never had a day of school in their lives, they were scrupulous about telling the truth about what they had seen and suffered.”

Narratives

For modern audiences, the concept of the slave narratives was introduced in 2013 with the Academy Award-winning film, “12 Years a Slave,” based on Solomon Northup’s 1853 memoir, “Twelve Years a Slave.” Northup was a freeman who was kidnapped into slavery.

The book sold 10,000 copies within the first month of its release, becoming an instant hit. Northup was not alone as a literary influence.

“UNC’s Andrews said the oldest narrative that has been found is “The Last and Dying Words of Mark, aged about 30 years” which was a broadside confession of a former slave who was executed for killing his master in 1755.

That was followed by seminal works like, “The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Written by Himself (1789);” “The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave (1831)” which was the first known narrative written by a woman; and Booker T. Washington’s “Up from Slavery (1901).”

But two pieces stand at the summit: “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845),” and Harriet Jacobs’ “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861),” historians say.

Douglass was able to hone and perfect what became the first of his three autobiographies by telling his story of slavery and emancipation on the lecture circuit.

“When he got to the North and joined the anti-slavery movement as a lecturer, he told his story so often from the lectern that by the time he brought the narrative out, he had developed a keen sense of what worked and what stories were most powerful,” Andrews said. “The “Narrative of Frederick Douglass” is rhetorically a very sophisticated piece of writing. It is a classic in the canon of American autobiographies.”

Terrible for women

Published in 1861, Jacobs’ account of rape and the sexual abuse faced by female slaves who were forced to not only protect themselves, but their children, was harrowing and stark.

“Slavery is terrible for men,” Jacobs soberly wrote. “But it is far more terrible for women.”

Because Jacobs wrote the book under the pseudonym Linda Brent and because it was so vivid in its descriptions—including passages about her hiding in an attic for seven years—scholars thought for decades that it was a novel.

“She wasn’t writing to end [The Civil War],” said Moody, the editor of “A History of African American Autobiography.” “She was writing to end slavery.”

When Andrews came to UNC in 1996, he joined a project underway at the University Libraries there to digitize all of the known book-length narratives, which number more than 200. Today, more than a million people visit the archive annually.

“The super famous people like Frederick Douglass and Harriett Jacobs are famous for a good reason,” Andrews said. “But there are so many more narratives by people who were much more typical of the rank and file, the average enslaved man or woman. Their stories also deserve to be read and studied.”

Influences

To examine the influence of slave narratives, consider that Harriett Beecher Stowe, author of one of the most influential novels of the 19th century, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” said she could not have written it had she not read slave narratives.

One of the most taught and discussed American novels of the first half of the 20th century, Mark Twain’s “Huckleberry Finn,” was essentially a slave narrative about a white kid who runs away down the Mississippi River with a fugitive slave.

But Black writers—through Reconstruction, the Harlem Renaissance, the Black Arts Movement and even today—have faithfully carried forth the traditions.

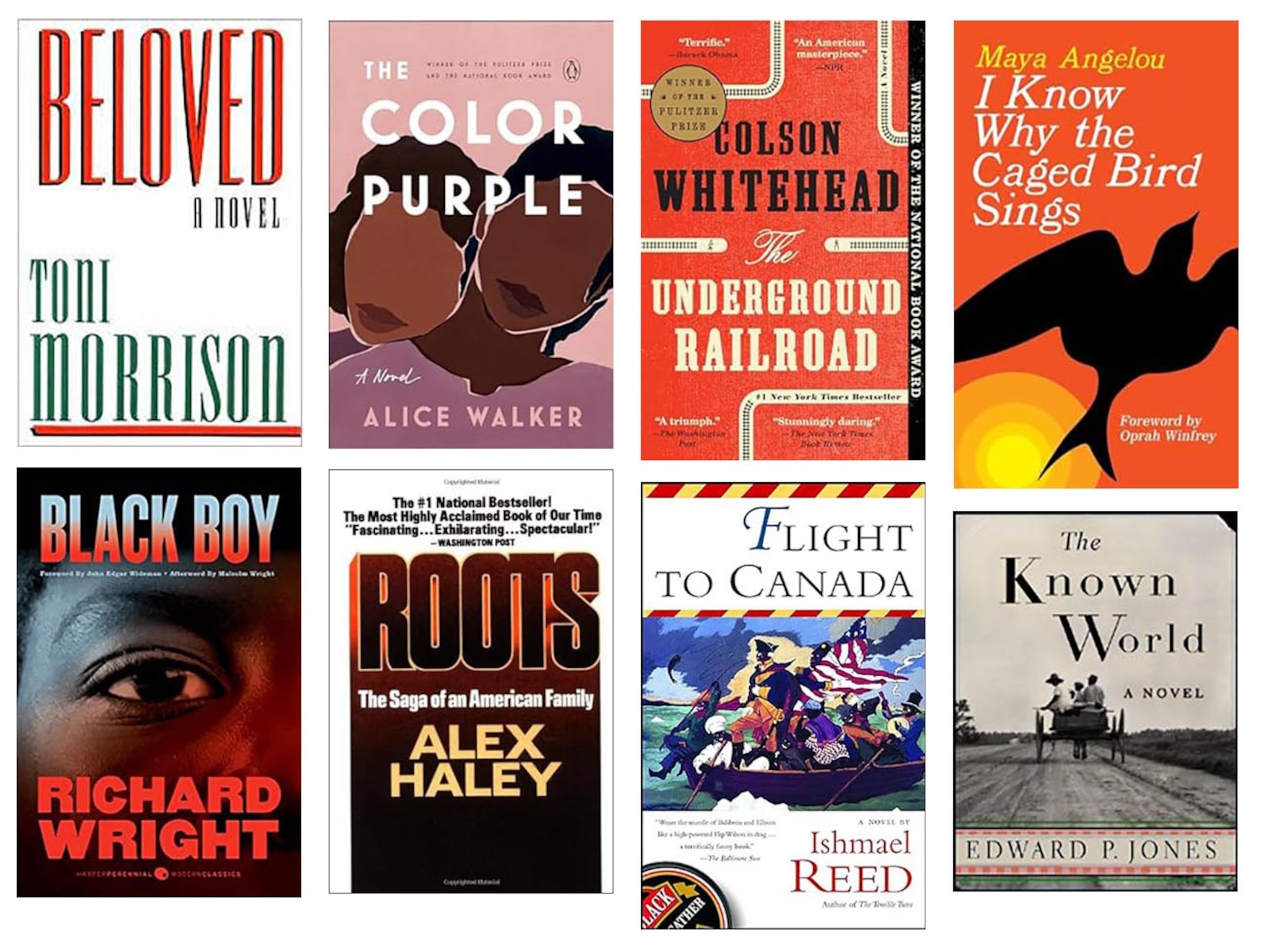

Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” which is based on the actual case of Margaret Garner, who killed her daughter rather than allow the child to be returned to slavery, is a slave narrative.

So are “Roots” and “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” by Alex Haley.

“The Known World,” by Edward P. Jones.

“The Underground Railroad” by Colson Whitehead.

“The Color Purple” by Alice Walker.

“I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,” by Maya Angelou.

“Black Boy” by Richard Wright.

“Flight to Canada,” by Ishmael Reed, a parody that he called a “neo–slave” narrative.

“They are in direct conversation with slavery,” Moody said. “The Harlem Renaissance was about creating the New Negro. But there was no escaping it. There is no getting away from enslavement.”