Author and academic Regina Bradley can remember the exact moment she heard OutKast for the first time.

The year was 1995. Her parents let her to stay up late to watch an episode of the sitcom, “Martin.” The episode, “All the Players Came,” features the title character, played by Martin Lawrence, hosting a 70s-themed party that includes Pam Grier, Isaac Hayes, Rudy Ray Moore and a closing performance of “Player’s Ball” by a young Andre 3000 and Big Boi.

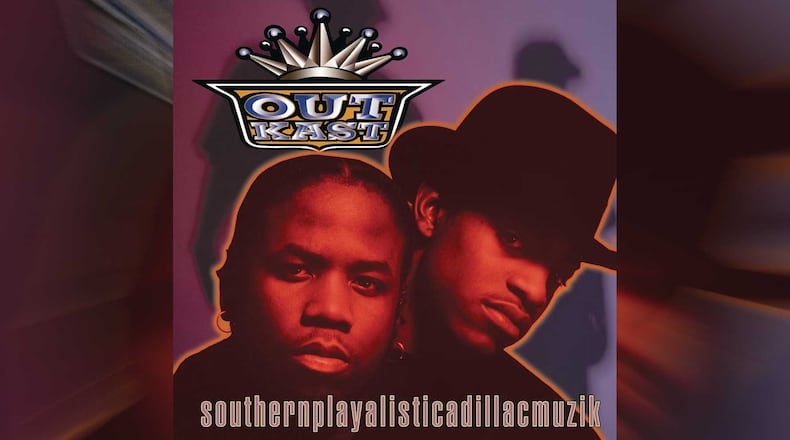

On April 26, 1994, almost a year before the episode aired, OutKast released their debut album, “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik,” on LaFace Records. The album marked a shift in Atlanta hip-hop’s trajectory in how folks above the Mason-Dixon Line viewed their country cousins’ lyrical competency. It was produced by Organized Noize who drew upon their funk and church influences while incorporating live instrumentation into the sample-heavy fold of 1990s hip-hop.

The lyrics, most of which were written by its creators when they were teenagers, touch on everything from self-expression, masculinity and spirituality, all while embracing being an Atlantan, Southern and Black. The album’s reception paled in comparison to the group’s 2003 double album, “Speakerboxxx/The Love Below,” which went on to win album of the year at the Grammys and become the highest-selling rap album of all time on the strength of singles such as “Hey Ya” and “The Way You Move.”

Credit: ERIC WILLIAMS�

Credit: ERIC WILLIAMS�

As the album approaches its 30th birthday, Bradley, now an associate professor of English and African diaspora studies at Kennesaw State University (KSU), thinks “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik” should be recognized as a crucial piece of Black history.

“To just freely create something so gorgeous and on their own terms is something I think was really overlooked and underappreciated. But I think we’re starting to appreciate that now 30 years later,” said Bradley, who teaches a course at KSU called Black Popular Culture: The OutKast Class.

Bradley is also the author of the book “Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South,” which takes a deep-dive into how the work of OutKast inspired new possibilities in Black thought. For scholars like Bradley, studying OutKast, specifically “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik,” is as crucial to understanding Black Atlanta’s story as James Baldwin’s “The Evidence of Things Unseen,” Maurice Hobson’s “The Legend of the Black Mecca” and Tayari Jones’ “Leaving Atlanta.” If anything, with its almost photorealistic lyrical depictions of everyday life for working- to middle-class Black folks, it can and should be read like a text.

Long before Andre 3000 made his “the South got something to say” claim at the 1995 Source Awards, it was clear by listening to OutKast’s debut that in many ways, as Black Southern men, they felt overlooked and undervalued. Like Frederick Douglass before them, OutKast was leveraging the art of storytelling from a long line of Southern, Black orators speaking up about the realities of being an outcast in America, according to Lakeyta Bonnette-Bailey, a professor at Georgia State University.

“They needed the outlet, and hip-hop was providing an outlet to create these narratives, to tell the narratives of what is going on in the South. ‘Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik’ follows in this long oratorical tradition, especially in the South, but especially with Black leaders,” she said.

Bailey serves on the advisory board of Georgia State Library’s Atlanta Hip-Hop Archives, which opened in November 2023. The project, led by curator Brittany Newberry, is a collection of artifacts, materials and oral histories that tell the city’s hip-hop story from 1980 to present day.

When “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik” was released, Atlanta was a city in transition. The Olympic Games were two years away. Freaknik was at its peak. In the years leading up these events, Andre 3000, Big Boi and other young Black youth faced serious threats. Whether it was the Atlanta child murders or the infamous run of the Atlanta Police Department’s Red Dog unit, you could feel real-life fear of these traumas through the poetry of two local teens.

“You hear them shout out different people’s names, calling out streets, a lot of embedded political messages about what was going on in the city of Atlanta, but also what was going on with culture and lifestyle,” said Newberry.

Songs such as “Myintrotoletyouknow” and “Claimin’ True” dealt with Black mental health and generational tension within the community. These were issues that affected Black people in general, not just in Atlanta. On the track “D.E.E.P.,” listeners are greeted by a voice made to sound like an alien before the duo rips into their verses about aspiring for something greater, mentally.

In that way, the group embraces the Afrofuturist blueprints set forth by artists like Sun Ra, Parliament-Funkadelic and Nona Hendryx before them. It’s why the group’s work is currently being celebrated at the National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., as part of their exhibition, “Afrofuturism: A History of Black Futures.” The collection features a journal from Andre 3000′s teen years scribbled with notes, doodles and ideas. There is also poster that once hung in his room that features an alien on it.

Including OutKast in the collection was a no-brainer for curator Kevin Strait, who says their music, particularly on albums such as “Southerplayalisticadillacmuzik” and “ATLiens,” reflected a sense of alienation about being Southern hip-hop artists, as well as writing music that addressed the challenges of Black life in the American South. That, Strait says, is translated via the groups videos and legendary fashion choices. “They’re also offering music in a visual sense that communicates ideas about Black futures that connect across genres and geographic lines through escape, through fantasy, or just through perhaps reconceptualizing where they are and how they fit,” said Strait.

Bradley is glad to see more conversations about OutKast showing up in academia, museum spaces and during celebrations like Black History Month. Like great texts before it, she says “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik” is telling oft-forgotten stories about Atlanta and Black life.

“It was elevating the city and elevating communities in particular ways that politicians at the time maybe weren’t focusing on,” she said. “So, in that way, it’s like an archive.”

ABOUT THIS SERIES

The AJC’s Black History Month series focuses on the role of African Americans and the Arts and the overwhelming influence it has had on American culture. These daily offerings appear throughout the paper. More subscriber exclusives on the African American people, places and organizations that have changed the world are available at ajc.com/news/atlanta-black-history

About the Author

The Latest

Featured