Why an early silent film kiss between two Black actors is so important

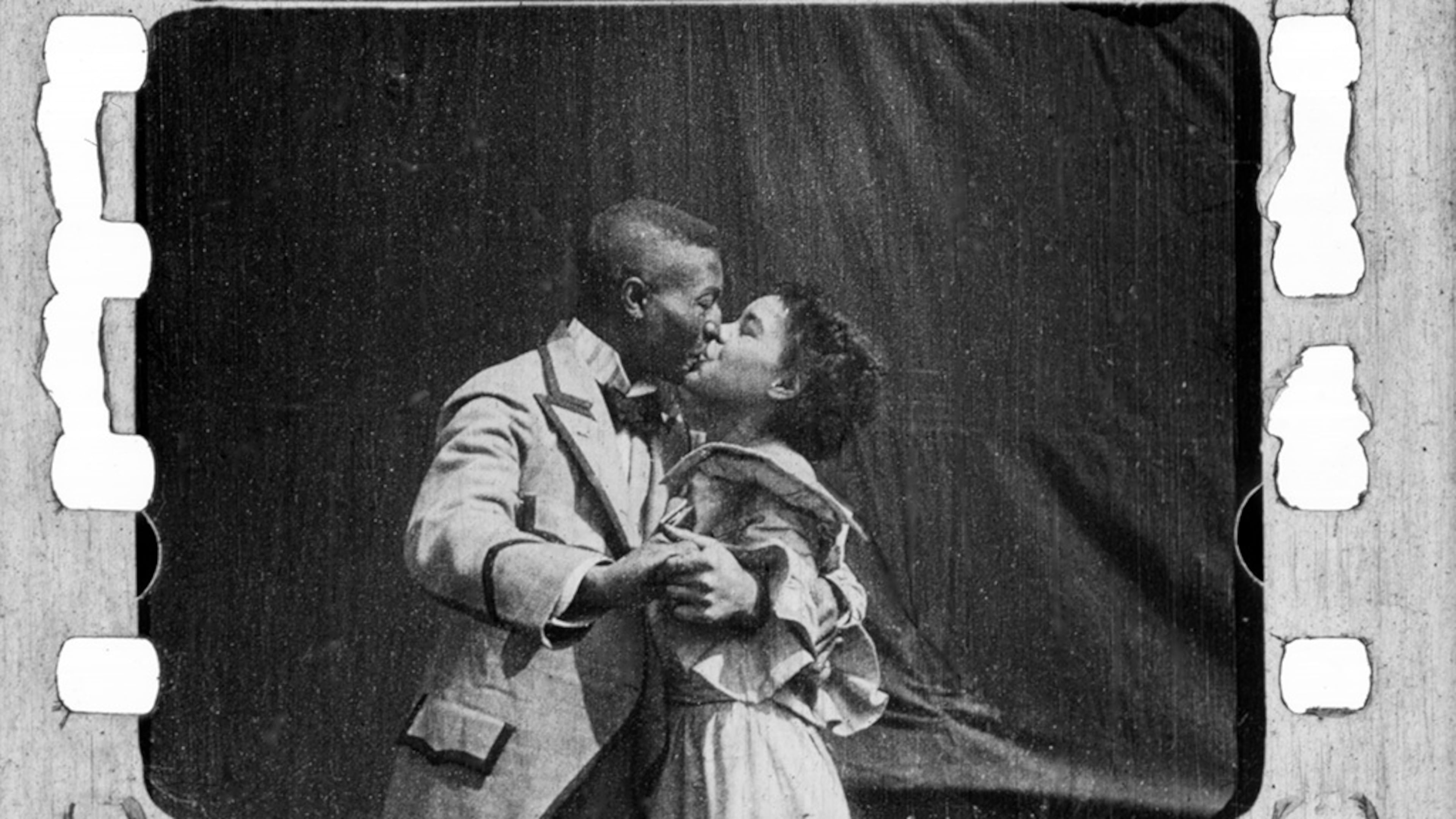

Against a backdrop of minstrelsy shows of the time, that showed Black people in torn and tattered clothes with bugged-out eyes and grotesque lips, often limited to exaggerated and dehumanizing bestial stereotypes stood a neatly dressed couple in Victorian-era clothing. Their eyes are locked on each other. Their lips seek affection.

And for 20 seconds at least — in a moment lost for more than a century since 1898 — there was something good.

A recently discovered film clip of a well-dressed Black couple swinging in each other’s arms in a joyous embrace, laughing, joking, teasing and most important, kissing, offers one the earliest cinematic depictions of affection between a Black man and woman.

The groundbreaking film is called simply, “Something Good — Negro Kiss.”

The discovery of the film almost didn’t happen. In 2017, Dino Everett, a film archivist at the University of Southern California’s HMH Moving Image Archive, was digging through old nitrate reels when he came upon one that a Louisiana collector sent him three years earlier.

Most random reels that archivists are sent have no historical or cinematic value, but when Everett looked and saw a joyful Black couple kissing, he knew that he had something special.

“I went to class that night and told my students, ‘I don’t know what this is yet, but I am pretty sure this is the most important film in my catalog,’” Everett said.

For verification, Everett sent a note and a still of the film to Allyson Nadia Field, an associate professor of film and media studies at the University of Chicago, who specializes in the intersection of race and cinema.

“Yes, it was very important,” said Field, the author of “Uplift Cinema: The Emergence of African American Film and the Possibility of Black Modernity.” “It was like something I’ve never seen before. We were looking at something quite remarkable and something that we didn’t think could have been made at the time that it was made and that we didn’t think existed.”

As early as 1894, according to the Library of Congress, short anthropological pieces depicting Black people were being made and did not show intimacy or humanity.

Field and Everette did some research through inventory and distribution catalogs and discovered the film they discovered was made by William Sellig, a white, Chicago-based American filmmaker who shot films in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

“Something Good — Negro Kiss,” was always listed on inventories, but because it was lost, scholars like Field and Everett assumed it contained the same kind of stereotypical images from films like Thomas Edison’s 1896 “Watermelon Eating Contest” or “Who Said Chicken,” from 1900.

“Early cinema is egregious for this and replete with all kinds of stereotypes,” Field said. “So we see images like watermelon eating contests or gags where a mother is trying to wash the skin color off the baby. Those were our early images of Black people that we were used to seeing - those racist stereotypes.”

“Something Good — Negro Kiss,” starred noted vaudeville performers Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown, who were members of The Rag-Time Four, a vaudeville quartet out of Chicago.

After shooting the film, Suttle continued to perform and write music until he died in 1932.

Brown went on to marry Tim Moore of “Amos & Andy” fame, and the two toured the country as Tim & Gertie Moore. She died in 1934 of double pneumonia.

Field, who is writing a book about the rediscovery of the film, said Suttle and Brown were likely hired to cakewalk in the film and were later encouraged to kiss.

They surmise it might have been a response to the 1896 film, “The May Irwin Kiss,” one of the first films ever shown commercially to the public.

“Something Good — Negro Kiss,” was likely shown to white audiences as a comedic short alongside films that depicted stereotypical Blacks or whites in blackface. Field is unclear on what the reception was or if the showing of love and intimacy had a cultural impact on the thinking at the time as such scenes were generally not shown in white-dominated settings.

Everett said that when he watched the film, he kept waiting for a punchline. A joke.

“So for this to exist of just two Black people being joyful and exhibiting love is unique. This is not like any other film,” Everette said.

When the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts released the film online in 2018, it immediately went viral. Noted Black actress Viola Davis said simply: “Love, love, love this!!! #BlackLove. We’re not crying you are”

In 2021, following the attention and buzz, a different unidentified extended cut, that had been sitting in the National Library of Norway for decades, surfaced. It was about 30 seconds longer and shot at a wider angle, the extended cut — which might have been made for an international audience shows an even more playful Suttle and Brown, who end the shot with a dramatic twirl in addition to the kiss.

According to the National Film Preservation Board, fewer than 20 percent of American films made during the silent era survive in complete form. Taking it a step further, Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation estimates that more than half of all American films made before 1950 are lost.

The data does not indicate the race of the filmmakers or the stars, but it is assumed that Black or “race films,” suffered tremendous loss.

Take Oscar Micheaux, one of the first and most prominent Black filmmakers of his time, known for films like “Within Our Gates,” and “The Symbol of the Unconquered.”

But his very first film, “The Homesteader,” is lost. As are “The Brute” (1920), “The Gunsaulus Mystery” (1921), “Birthright” (1924), “The House Behind the Cedars” (1924), “The Conjure Woman” (1926), “The Spider’s Web” (1927), and “The Wages of Sin” (1928).

Which makes the discovery of “Something Good — Negro Kiss,” all the more remarkable.

Since its rediscovery, several artists and creatives have re-interpreted it.

In January, Grammy award-winning tenor saxophonist Kebbi Williams and director and choreographer T. Lang, put together a musical and dance tribute called, “Black Kiss (Still Good).”

Marking Williams’ 50th birthday, it was 60 minutes of slow movements and gestures against a sensuous score.

“I crave wanting to see simplicity and mundane and peaceful and caring and deliberate tenderness of Black love that puts it right in your face,” Lang said. “I want to see more of that type of pleasure, expressions and representations. And folks in 1898 were wanting to see that too.”

In 2018, “Something Good — Negro Kiss” was added to the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry as a film deemed culturally significant.