SAVANNAH — As a boy in the Bronx, Jerome Meadows dreamed of Michelangelo.

He’d spend his spare waking hours drawing or painting horses in the style of the master artist — hyper-realistic with highly articulated musculature — only to talk with and create with the sculptor and painter after he’d gone to sleep. Some nights, the two would discuss Meadows’ favorite Michelangelo works, a series of statues known as “The Prisoners” or “The Slaves” because the forms are only partly carved free of the stones.

The works are among the Renaissance man’s most mystifying. To Michelangelo, every block of stone hid a figure, and he considered it his job to release it, be it David or Bacchus or Angel. He never explained why these forms never escaped the rock.

For a teenage Meadows, the sculptures took on special meaning. He felt as trapped by life in one of New York’s poorest neighborhoods as Michelangelo’s slaves were in those stones. He resolved to break free and rise above his circumstances.

It’s a personal ethos that has guided Meadows’ accomplished art career in the decades since. His talent took him from the Bronx to the Rhode Island School of Design. From there, he became a nationally renowned creator of public art pieces, specializing in African American heritage and the horrors of America’s racist past.

At his MeadowLark Studio on Savannah’s eastside, he creates emotionally powerful works, both large and small, to be experienced by broad audiences. His local pieces include statuary in Yamacraw Square, and Meadows is the only Black artist featured in one of Savannah’s instantly recognizable downtown greenspaces.

At home in adopted home

Meadows was feeling trapped again in 1997 when Savannah leaders contacted Meadows about sharing his creativity with the city.

He was living in Washington, D.C., teaching at Howard University, and growing frustrated by his career path. He’d completed several profile-raising public art projects in the nation’s capital and was frequently being courted by art collectors to create pieces for them.

He found many of his potential clients to be pretentious and self-serving.

“They were so full of themselves,” he said. “The attitude was if you’re going to be successful, it’s because I’m going to make you, and you’re going to be have to brand yourself as a certain type and style of artist.”

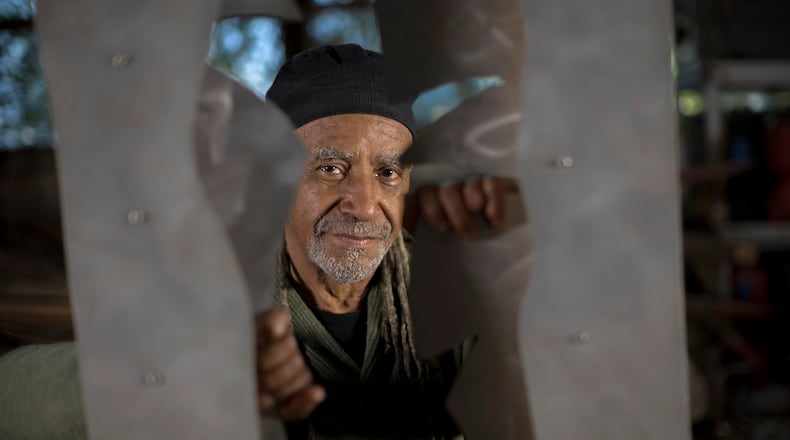

Credit: Stephen B. Morton for The Atlanta Journal Constitution

Credit: Stephen B. Morton for The Atlanta Journal Constitution

Meadows had grown weary of searching for affordable art studio space in Washington. So when he got a call about creating a public art park in Savannah, near the site of a church established by a freed slave named Andrew Bryan in 1788, he headed south on I-95.

He fell in love with a piece of property, a cavernous century-old brick icehouse, serendipitously listed for sale by a real estate agent who was also one of the Yamacraw project’s champions.

The Yamacraw Art Park project would ultimately turn problematic and take 25 years to fulfill its promise with the 2022 dedication of Yamacraw Square, but Meadows had found his home. He quickly became a pillar of an emerging art city, engaging the community in multiple ways, from leading poetry readings to hosting jazz music hours on the Savannah State University radio station and an “Art Talks/Art Matters” TV show on the local government television channel.

Credit: Stephen B. Morton for The Atlanta Journal Constitution

Credit: Stephen B. Morton for The Atlanta Journal Constitution

Kris Monroe, a Savannah arts advocate and the chair of the Savannah-Chatham County Historic Site and Monument Commission, said Meadows has been a leader in elevating important common spaces and challenging Savannah’s traditional arts scene to reach beyond its comfort zone.

“He alone has generated a particular type of creative energy that would otherwise be lacking,” Monroe said.

An impressive portfolio

Meadows’ work is easy to find in Savannah. In addition to the art park in Yamacraw Square, he created the installation outside the city’s newly opened sports and entertainment venue, Enmarket Arena.

Meadows’ creations are the centerpieces of community art centers across the country, from a concourse at Dallas-Fort Worth Airport to the streets of Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

His memorial to a lynching victim in Chattanooga, Tennessee, has gained him new levels of acclaim since it opened in late 2021. The artwork features three statues and tells the story of Ed Johnson, a Black man accused of raping a white woman in 1906, two Black attorneys who fought Johnson’s cause all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, and Johnson’s lynching by a white mob. Johnson was hung from a girder of the Walnut Street Bridge, at the time the main connection between Chattanooga’s Black residential neighborhoods and its city center.

Meadows was working on the project during a period of racial protest following the police killing of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. The statues represent grace, compassion and courage, he said.

While he abhors the notion of his art having a “brand,” the combination of grace, compassion and courage has become a foundational theme for Meadows. His Savannah studio includes a gallery home to dozens of collage art pieces focused on current events and the civil and racial strife America faces today.

His art is his solution.

“For me, it comes down to this: Are you creating art that’s creating impact where it is needed?” Meadows said.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured