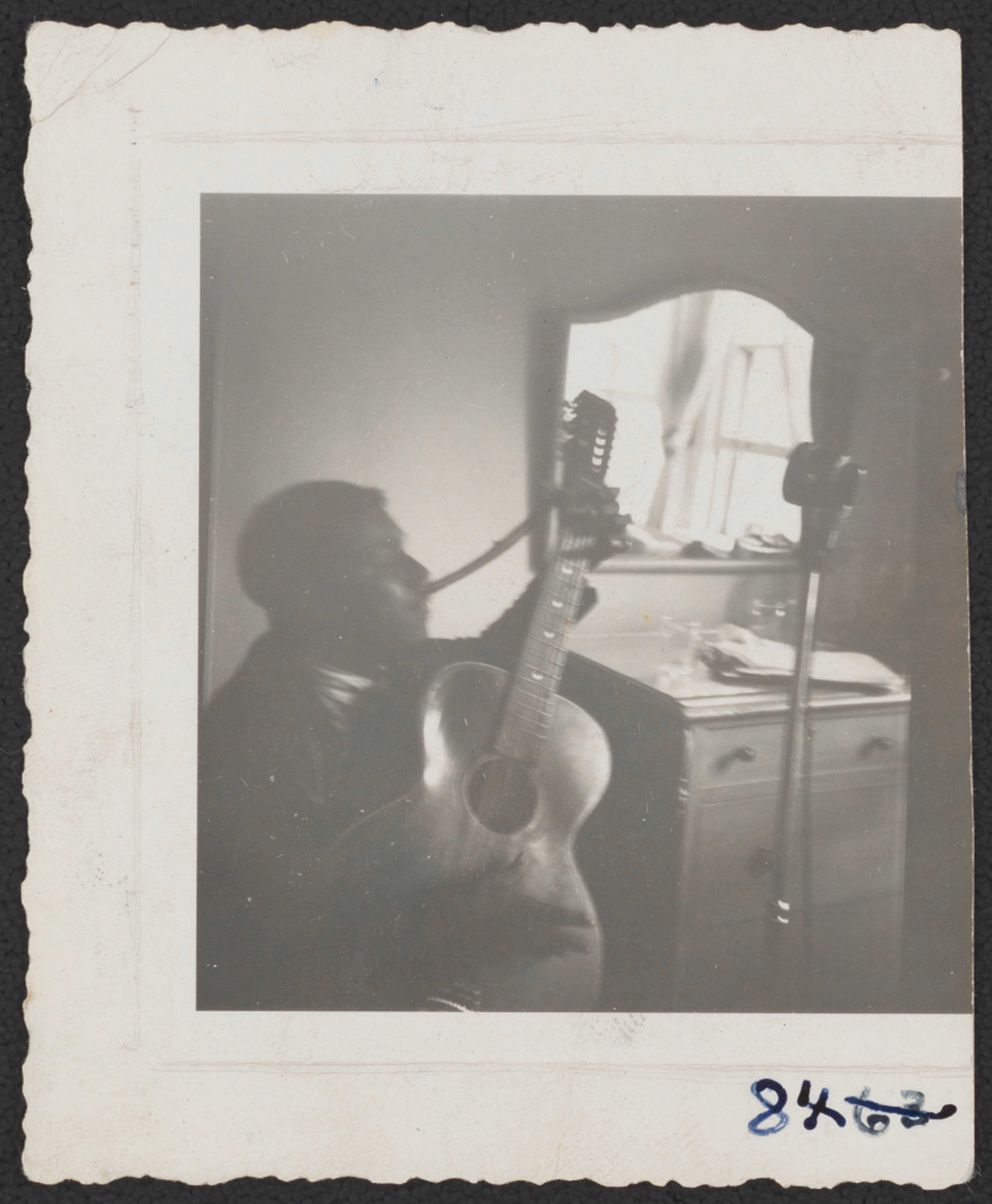

Georgia’s 12-string master left a lasting musical legacy

Here’s a trivia question you can use to stump fellow music nerds.

This Georgia-born, Black artist influenced musicians from the Allman Brothers to Bob Dylan to the White Stripes. There’s an annual music festival in his hometown, a mile-long walking trail in his honor in another Georgia city where he spent much of his boyhood, and an Atlanta nightclub that bears his name. He’s in the Georgia Music Hall of Fame, and one of his signature songs is included in the “500 songs that shaped rock and roll,” assembled by the chief curator of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

The answer isn’t Little Richard or Otis Redding. And it’s not Ray Charles or James Brown. It’s Blind Willie McTell, a 12-string guitar bluesman who recorded dozens of songs in the 1920s and 1930s, died in obscurity in 1959, but whose music continues to inspire artists today.

“It’s a revelation to your ears,” Nashville-based singer-songwriter Adia Victoria said about hearing McTell for the first time.

Victoria, a South Carolina native, dove into blues music while living in Atlanta more than a decade ago. During that time, she found a recording on YouTube of McTell’s “You Was Born to Die.”

Victoria grew up in the Seventh Day Adventist Church where discussions about death centered on resurrection and the afterlife, rather than about death as part of life. McTell’s frank and honest song about the ultimate path everyone walks was “strangely reassuring,” she said.

“You were specifically born to do what everybody that’s been born does: die,” she said. “And to hear someone put it plainly like that, and make a beautiful piece of art out of it? I don’t know. I guess it did something to alleviate anxiety in me.”

Victoria decided to cover the song for her 2021 album “A Southern Gothic” and brought in fellow artists Kyshona Armstrong, Margo Price and Jason Isbell as guest vocalists and musicians on the track.

First recorded by McTell in 1933 as a duet with fellow Atlanta bluesman Curley Weaver, “You Was Born To Die” is sung in the first person to an unfaithful lover. Weaver takes the lead with his baritone voice: “Don’t want no woman that runs around/Stay out in the street like a badfoot clown.” McTell joins in on the chorus in his unmistakable tenor: “You made me love you and you made me cry/You should remember, that you were born to die.”

Victoria said her discovery of McTell and a pantheon of other blues artists was like finding “a really cool group of ancestors.”

“I remember feeling like a door had been opened up for me that connected me to my blackness, my Southern identity growing up in poverty. All of these things came together for me in a way that they hadn’t before,” she said. “They sang my soul to me. They gave me access to my soul. They allowed me to claim all the parts of me that I had been raised to believe that there was something wrong with.”

Yet few casual music fans know of McTell and his impact on popular music.

In 1971 when the Allman Brothers Band ripped into their rendition of “Statesboro Blues” in concert at the Fillmore East in New York City, few in the audience recognized it as a song written and recorded by McTell decades earlier. If anything, some might have believed the Allmans were covering crossover blues guitarist Taj Mahal, who had recorded a version of the song for his 1968 debut album.

Even blues fans in Atlanta who have spent evenings at Blind Willie’s in the Virginia Highlands may not be familiar with the iconic club’s namesake. However, even if he isn’t as well known as blues contemporaries Robert Johnson or Lead Belly, McTell’s legacy is no less durable.

Georgia legend

McTell was born around 1903 (dates vary) in Thomson, about 25 miles west of Augusta, but spent much of his childhood in Statesboro. He was blind, either from birth or at a young age, and was educated at several schools for the blind, including the Georgia Academy for the Blind where he took formal music lessons and learned to read and write in braille.

As an adult, McTell worked in the streets and house parties in Atlanta’s Sweet Auburn District in a time when blues music was growing in commercial popularity and white-owned record labels scoured the South for artists who could play and sing in the new style. During the 1920s and 1930s, McTell traveled to Chicago and New York to record more than 60 songs for Columbia, Decca, Okeh and Victor — the premier recording companies for the “race” records of the period.

McTell’s performances stand out from his contemporaries. His playful songwriting, his choice of instrument and stylistic choices — ranging from ragtime to spirituals to straight blues — separated him from the dark, brooding sounds of the Mississippi Delta. But changing tastes, the Great Depression, the rationing of shellac during World War II, and the brutal contracts offered by white-owned record companies left McTell to scratch out a living as an itinerant musician.

His records went out of print and McTell was left playing for tips and taking requests in parking lots in Atlanta.

He might have faded entirely into obscurity had a white Atlanta record store owner not convinced McTell to sing 13 songs, interspersed with commentary, into a reel-to-reel tape recorder in 1956. According to McTell biographer Michael Gray, the tape of the bluesman’s “last session” was dumped in a box for several years until it was rediscovered during the folk revival of the late 1950s and released as an album.

The success of that recording sparked an interest in McTell’s earlier work. Like so many of his generation, his “rediscovery” by white blues fans came too late for McTell to enjoy. He died in 1959 of a brain hemorrhage, but the reemergence of McTell’s recordings in the 1960s and 1970s reached a new generation of fans.

An ‘immense talent’

Atlanta author David Fulmer first heard McTell’s music in 1973 while serving overseas in the Army when he stumbled across a record of McTell’s later recordings in the PX.

“I was completely enthralled and taken with him,” Fulmer recalled. “What jumped off this record to me is this guy is a consummate performer.”

An amateur guitar player himself, Fulmer was floored by McTell’s transitions from strumming to finger-picking to slide guitar, sometimes within the same song. McTell punctuated his virtuoso playing with his tenor vocals and lyrics that ranged from playful to deeply serious.

In the bouncy, ragtime-influenced “Kill It Kid,” McTell sang about a swinging time in a Miami dancehall.

“You know, Sister Kate took brother Mo, bounced him around across the floor,” he sang.

In “On the Cooling Board,” McTell spun a somber tale about the death of a lover: “Undertaker, undertaker, please take it slow. You’re taking the one I love; won’t bring her back no more.”

Fulmer knew about blues music and loved legends like Robert Johnson and Son House, whose mysterious, moaning style from the Mississippi Delta mimicked the field hollers of the prior century. But McTell was different — bigger, brighter and more urban.

“I had a good enough ear so I could recognize what an immense talent I had stumbled onto,” Fulmer said.

Years later, after relocating to Atlanta, Fulmer scraped together enough funding to film an hour-long documentary about McTell’s life, placing his career in the broader context of the Black experience in the first half of the 20th century. For him, the film was a way to preserve and promote McTell as an important artist who never saw the success or fortune he earned.

“He just always struck me as a superbly talented artist, and he was kind of cheated out of his due by the fact that he died just before the folk revival,” Fulmer said.

Victoria said McTell’s story isn’t unique. In fact, it was a system designed to cheat, she said.

“I think that our system has a way of creating a lot of convenient, happy accidents that work out in favor for white people,” she said. “It’s hard enough for someone today — a black artist today — to hear their music in the mainstream. But can you imagine this dude back then? He didn’t stand chance.”

But McTell’s music has endured. His broad musical choices and often cheeky lyrics have made his songs — the earliest of which are now approaching a century old — fertile ground for covering over the decades.

Along with Taj Mahal and the Allman Brothers Band, country legend Willie Nelson and folk artists Steve Goodman and David Bromberg have recorded versions of McTell’s songs. And in 1991 Dylan released “Blind Willie McTell,” a song he recorded in 1983 that weaves gothic Southern imagery around a tribute to the artist. Dylan also covered McTell’s “Broke Down Engine” for his 1993 album “World Gone Wrong.”

In 2014, former White Stripes frontman Jack White led off his album “Lazaretto” with a banging, electrified version of McTell’s boastful “Three Women Blues.” It wasn’t White’s first cover of McTell. The White Stripes recorded two other McTell songs, “Your Southern Can Is Mine” and “Lord, Send Me an Angel.”

Victoria said she believes McTell’s work continues to resonate with artists and audiences because his music reflects his focus and determination.

“And it shows in all of his music, just the complexity of the virtuosity,” she said. “I think that is one of the reasons it has lasted, why it has endured.”