Editor’s Note: This story is one in a series of Black History Month stories that explores the role of resistance to oppression in the Black community.

Cecil Williams was just thirsty.

And in 1956 in rural South Carolina, being thirsty could get you lynched.

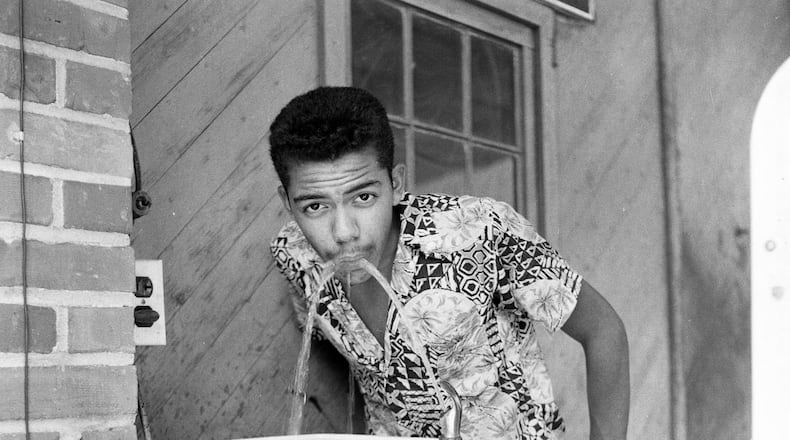

But there he was on Highway 21 on his way back home to Orangeburg, when he stopped to get a drink of water from a white’s only water fountain. By chance, a friend of his snapped his photo.

The photo sat undeveloped for more than 50 years. Now Nearly 70 years later, after it was published in 2006, the photo is the stuff of legends, while also being a reminder of what could have been.

“It was dangerous to do things like that during that era,” Williams said. “Grave things happened to people of color when we broke the rules.”

Williams is now 85 years old and recognized, through his work with major Black publications covering race, as the dean of South Carolina’s Black civil rights journalists.

Born in Orangeburg in 1937 to a schoolteacher and a tailor, Williams is a true son of South Carolina. He was nine years old when he got his first camera and by 14, he was freelancing for Jet! and Ebony magazines, covering race in South Carolina.

“They needed people like me on the ground,” said Williams, who was jailed at least twice covering the news. “And if it happened in South Carolina, I was there.”

Every protest, every march, Williams was there. Including Harvey Gantt’s 1963 desegregation of Clemson University and the 1968 Orangeburg Massacre, where state highway patrolmen opened fire on about 200 unarmed Black student protestors, killing three teenagers and wounding 28.

Credit: Courtesy Cecil Williams

Credit: Courtesy Cecil Williams

He graduated with an art degree from Claflin College in 1960, right around the time he became the official photographer for the school and for South Carolina State University.

He has published four books based on his photography and in 2019, with “$67,000 and $10 million worth of passion,” he opened the 3,500-square-foot Cecil Williams South Carolina Civil Rights Museum on a plot of land next door to his home.

“We knew this was something to show today’s generation that not only did we play an important role in South Carolina,” Williams said. “But that we are the catalyst of the American civil rights movement.”

But for all of the history he has documented, it is the photo of him that people want to talk about.

Credit: Courtesy Cecil Will

Credit: Courtesy Cecil Will

To understand the meaning behind the photo. One must understand the times and what people now take for granted.

On a hot summer day in 1956, Williams and his buddy Rendall Harper were returning to Orangeburg from an assignment on the coast.

Williams and Harper had not really had anything to drink all day, so they stopped at a tiny service station near Walterboro, about 30 miles outside of Orangeburg.

“I got thirsty, pulled into a service station, walked to the water fountain and started drinking,” Williams remembered.

The water fountain, clearly marked “White Only,” was situated just outside of the building near the garage door. There was no “Black” water fountain. Williams had no choice.

He took a drink.

Harper picked up Williams’ camera and snapped a picture. When it was Harper’s turn to get a drink, Williams returned the favor and snapped him.

A crowd of white people, getting their cars fixed or pumping gas, watched. No one said a word – perhaps stunned by what they were seeing.

This was just a year after Emmett Till, barely younger than Williams, was lynched in Mississippi for allegedly whistling at a white woman. It was a decade after Isaac Woodard, a World War II veteran was beaten and had his eyes gouged out by an angry mob after arguing with a bus driver in Batesburg-Leesville, S.C.

Williams had left the car running and his door open. They left quickly.

“It was not an attempt to be provocative,” Williams said. “There was no other fountain and we were thirsty. Today, I realize that it was a brazen thing to do. Especially at that young age.”

Williams is quick to say that he wasn’t smiling in the picture. But the 19-year-old looked like he knew he was getting away with something.

He was wearing his favorite summer shirt, a Hawaiian number unbuttoned down to his chest. His left hand, glittering with a gold watch, is resting on his hip. He is looking directly at the camera as the stream of ice-cold water parts his lips with a wispy teenage mustache.

Credit: Courtesy Cecil Williams

Credit: Courtesy Cecil Williams

Williams did not print or share the photo at the time, stashing it away among the thousands he has taken in his career.

But in 2006, he included it in his book, “Out-of-the-Box in Dixie,” a collection of his work.

It has become a cult favorite. A sign in the hip-hop and Black Lives Matter era of in-your-face resistance.

Rap songs have been made about Williams. T-shirts, cups, water bottles and lapel pins of Williams are on sale all over the internet.

Williams isn’t getting a penny for any of it. But in 2021, he was interviewed for the podcast, “Resistance.”

After his appearance, in his honor, the podcast started giving out awards to lesser-known Black people who showed extraordinary efforts of resisting.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

“It is very flattering because I never expected to get the attention,” said Williams. “I have gotten comments and messages from around the world that I couldn’t even read the language.”

Williams is still fighting and working. He is trying to put together a graphic novel about South Carolina’s civil rights history and is working on petitioning the U.S. Supreme Court to change the name of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case to Briggs v. Board of Education, to recognize the South Carolina family that was technically first on the lawsuit in alphabetical order.

Every day, when people come into the museum, they marvel at the photo of him at the water fountain. A replica fountain is in the museum and people line up behind it to get their photos taken. In his gift shop, he sells colorized versions of the photo.

“When I was a child,” Williams said. “My mother told me I was always trying to do things too big for my britches. I guess she was right.”

This year, the AJC’s Black History Month series will focus on the role of resistance to forms of oppression in the Black community. In addition to the traditional stories that we do on African American pioneers, these pieces will run in our Living and A sections every day this month. You can also go to ajc.com/black-history-month for more subscriber exclusives on the African American people, places and organizations that have changed the world.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured