Study: Toxins in blood of Brunswick residents who live near factories

BRUNSWICK — For most of her 74 years, Etta Brown has lived in the same few blocks of this coastal Georgia city, in the shadow of factories that tower over her neighborhood.

As a child, she splashed with friends in the puddles that would form after a heavy rain. She ate vegetables her father grew in their front yard. Crab boils and fish fries with seafood pulled from Brunswick’s trademark marshes were staples of summers as a kid, and later as a mother.

But she wonders if those pastimes, deeply engrained in the local culture, put her and her loved ones at risk.

A now-shuttered Hercules Inc. chemical plant nearby — the same one that provided a paycheck to her husband and uncle — produced a toxic pesticide, which it discharged into the surrounding marsh for years and buried in a landfill three miles away.

Last year, scientists from Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health began testing the blood of Brunswick residents for some manmade contaminants known to exist in the area, the first inquiry of its kind in years to investigate pollution exposure in the city.

In January, Brown joined nearly 100 others who rolled up their sleeves to have their blood tested for the study.

“I know they made some stuff there that they didn’t make anywhere else in the world,” Brown said, referring to the former Hercules factory, which produced pesticides and resins in her neighborhood for nearly 90 years until it closed in 2009. “I just want to know how it affected us and what can be done about it.”

Emory’s preliminary results revealed many participants with higher than normal blood levels of some of the area’s known toxic pollutants.

For now, Emory is only investigating the community’s exposure. But plans are in the works to potentially explore how chemicals made it into residents’ bodies, and, ultimately, whether their health has suffered.

Many of the factories that created the city’s pollution problems closed decades ago, and some are being remediated, but their toxic legacy lives on. Georgia has 18 locations on or proposed for listing as Superfund national priority sites, a federal designation reserved for the country’s most polluted properties requiring long-term cleanup. Four are located around Brunswick, including two connected to Hercules, more than any other city in Georgia.

Countless studies have found communities of color are more likely to breathe dirty air, live near hazardous waste sites and drink contaminated water. Still, many citizens of Brunswick — a mostly Black, lower-income city of more than 15,000 — contend the pollution around them has never been fully investigated.

Both the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Hercules said while they are aware of Emory’s research, each cautioned that the results have not been vetted by a peer-reviewed journal.

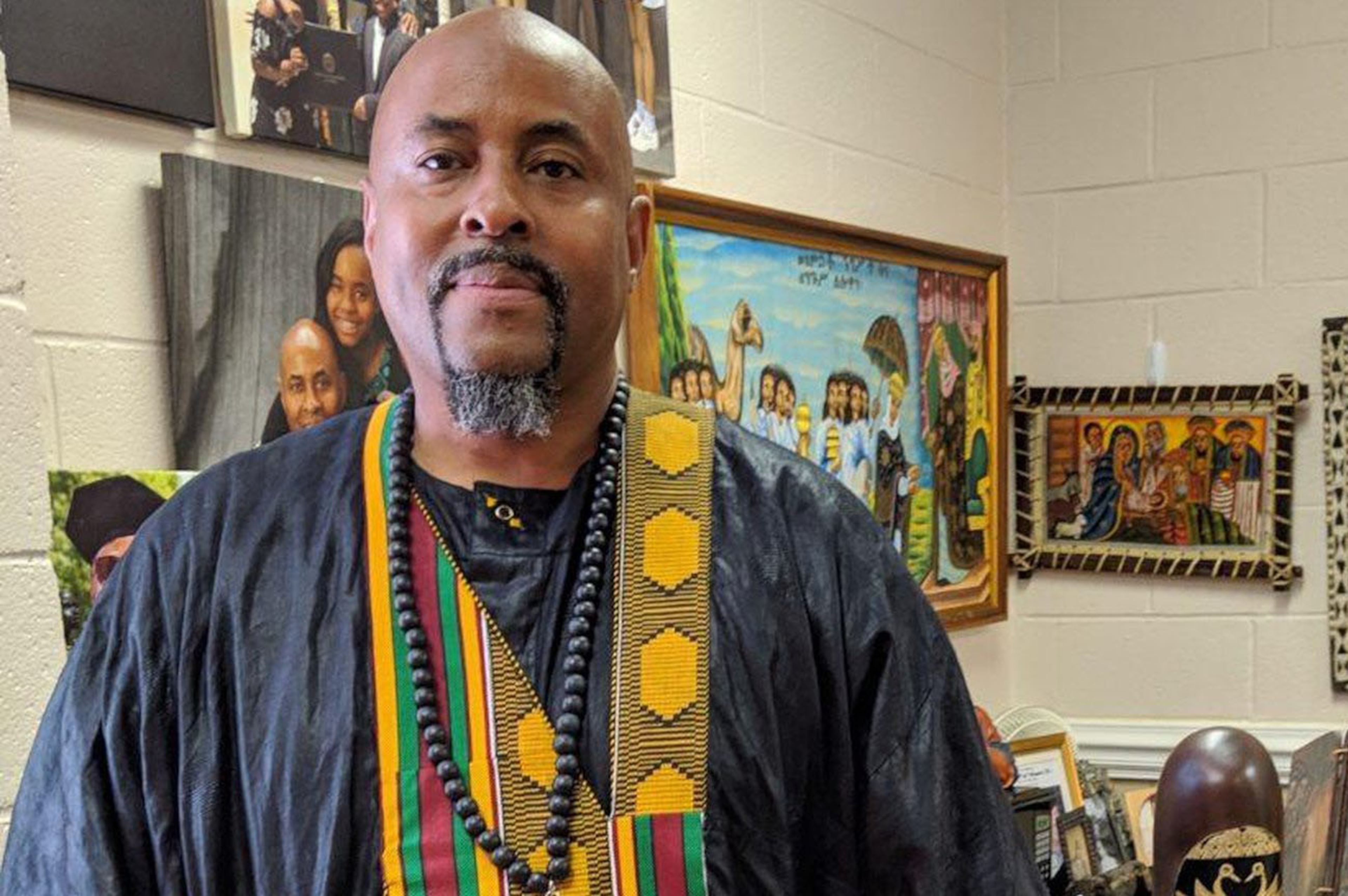

But Allen Booker, who represents most of Brunswick on the Glynn County Commission, said the study’s findings so far have validated their concerns.

“We are contaminated — this is not hearsay and they can’t dispute that,” said Booker, who helped create a Black-led advisory board that facilitated the study. High levels of some toxic chemicals were found in Booker’s blood.

“Now, we want to dig deeper into what else this means,” he said.

A history of pollution

Midway between Savannah and Jacksonville, Brunswick sits at the end of a marsh-flanked peninsula with access to the Atlantic Ocean. The city has been a major shipping and industrial hub for much of its history, home to chemical, wood, paper, paint and other manufacturing.

That heavy industry created good paying jobs, but took a toll on the environment. Glynn County has 14 sites on Georgia’s hazardous site registry, including the four Superfund sites.

The EPA is overseeing cleanup at two locations classified as Superfunds: wastewater drainage and dredge areas used by Hercules and a property known as the LCP Chemicals site.

Hercules produced rosins and other products at its Brunswick factory starting in 1920. But from the mid-1940s until 1980, it churned out a pesticide called toxaphene, which was developed as a replacement for DDT, the infamous pesticide whose devastating effects were documented in Rachel Carson’s classic book, Silent Spring.

Toxaphene was used to control the voracious boll weevil and other pests. But it, too, was harmful to wildlife and humans. It was banned in the U.S. in 1990 and is classified by the EPA as a probable human carcinogen.

The LCP Chemicals site, meanwhile, was home to an oil refinery, a power plant and, most recently, a chlorine factory that closed in 1994. Some of that heavy industry fouled soil, groundwater and almost 700 acres of surrounding marsh with dangerous pollutants, including mercury, lead and polychlorinated biphenyls or PCBs, a class of now-banned chemicals once used in transformers and other electrical equipment. PCBs are a probable human carcinogen and have been linked to immune system impairment, lower birth weight and neurological deficits.

Both toxaphene and PCBs persist in the environment and can build up in the tissue of creatures that consume them, as well as humans. That the toxins were released into the shifting tidal marshes around Brunswick makes tracking their spread even more challenging.

“It’s a very dynamic environment,” said Noah Scovronick, an assistant professor of environmental health at Emory who is part of the Brunswick study team. “When you combine that with the fact that many people rely on seafood for consumption, for recreation or for their livelihoods, it definitely adds up to a concern.”

Signs of exposure

Scovronick said their research uncovered only a handful of studies had been conducted on pollution exposure in Brunswick, with little examination of the general population.

The researchers enrolled 100 participants, with a mean age of 60 and an average time spent living in Glynn County of 47 years. About a third were male and almost half were Black.

In September, the researchers released preliminary findings that showed blood levels of certain toxic metals in the study group were comparable to the general population. But a significant number of participants showed higher-than-normal levels of three rare PCBs used at the LCP Chemicals site and for toxaphene, the Hercules-produced pesticide.

About four-in-10 participants had blood concentrations of a rare PCB that were higher than 95% of the U.S. population. About one-quarter also had toxaphene levels above those seen in nearly all of Canada’s population, which was used to compare because U.S. data is scarce.

At a public meeting in January, Scovronick’s team shared new results showing levels of some of the PCBs were more than twice as high in participants aged 60 and older, compared to younger ones. Older participants’ toxaphene levels were also slightly higher.

There also could be racial disparities. Higher levels of some PCBs were found in Black participants compared to white ones. For one of two types of toxaphene, Black participants also showed higher levels of exposure, but Scovronick said a larger sample size is needed to draw age and race conclusions.

Their results have not been peer-reviewed, but the researchers plan to soon submit their findings to an academic journal.

Exactly how chemicals ended up in peoples’ bodies is something researchers say needs further investigation, but they have some hypotheses. Employees of the Hercules and LCP Chemicals factories could have been exposed at work or brought the toxins home to their families.

Local seafood is also a potential source.

Anita Collins grew up near Hercules and heads a citizen-led planning group. She said fish and crabs plucked from the ocean and marshes were a “backdoor source of meals” for many.

“I remember going off to college and folks asked me, ‘What seafood restaurant do you patronize?’,” Collins said. “I said, ‘My mom’s kitchen table.’”

Fish consumption advisories exist for many of the estuaries and creeks around Brunswick, according to Georgia Environmental Protection Division guidelines. For many species, the latest edition recommends eating no more than one fish a week or month from certain areas, with clam, mussel and oyster harvesting prohibited. Around the drainage ditch used by Hercules, even less consumption is advised.

Locals say “no fishing” signs and city warnings about the safety of seafood from these areas are often missed or ignored.

Cleanups and next steps

While Emory’s initial findings come to light, cleanup is progressing in Brunswick.

With the EPA’s supervision, Hercules’ contractors are building a new, concrete-lined ditch and backfilling the existing one, which is expected to be complete this summer. After that, the EPA said it will begin an investigation into creek contamination and areas where dredge spoils were piled.

The multinational conglomerate Honeywell purchased the LCP Chemicals property in 1998 after LCP went bankrupt. In 2016, Honeywell, and Georgia Power, which once had a power station on the site, agreed to pay $29 million to remediate portions of 760 acres of polluted marsh along the Turtle River. That work was completed last year, but an EPA spokesman said the agency is still weighing options for cleaning up mercury contamination remaining beneath part of the site.

Emory’s study has gotten the attention of those involved.

The EPA met with the Emory researchers last fall and an agency spokesperson called their initial results “concerning.” But because the study did not delve into when, where or how exposures happened, the spokesperson said the findings “may be of limited value in our evaluation of the Superfund sites.”

Honeywell spokeswoman Victoria Streitfeld said in a statement the company is committed to returning the property “to uses consistent with public planning and health and safety protections.” On the Emory study, Georgia Power spokesman Jacob Hawkins said the company supports “efforts to understand and improve public health across Georgia.”

Timothy Hassett, Hercules’ remediation manager, said the company is aware of the research, but added that “it has not been published, shared with Hercules, or peer-reviewed.”

Hercules sold the Brunswick factory site to Pinova Inc., which produced resins there starting in 2010. Last April, a massive chemical fire destroyed much of the Pinova plant. Two months later, the company announced it would not reopen and soon the industrial relic that has loomed over the neighborhood for generations soon could be gone.

Pinova and its parent company, DRT, did not immediately respond to a request for comment, but a website for the factory says the decommissioning will last through 2024. After that, the website says the company “will consider and prepare the way for productive re-use of the site.”

Emory scientists, meanwhile, are planning next steps. The group is seeking National Institutes of Health funding to expand the research and depending on the study’s design, enroll an additional 400 participants. If successful, they want to explore links between certain diseases and known local pollutants, and how toxins entered residents’ bodies.

Brown, who has lived near the Hercules site for most of her life, said she is eager for more information.

“I’m a curious person,” Brown said. “I’m 74 now, but I’d like to know if I need to be aware of something that might get me later in life.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct references to Honeywell’s ownership of the former LCP Chemicals site.