Black communities burdened by air pollution may finally get answers

Editor’s Note: This story is one in a series of Black History Month stories that explores the role of resistance to oppression in the Black community.

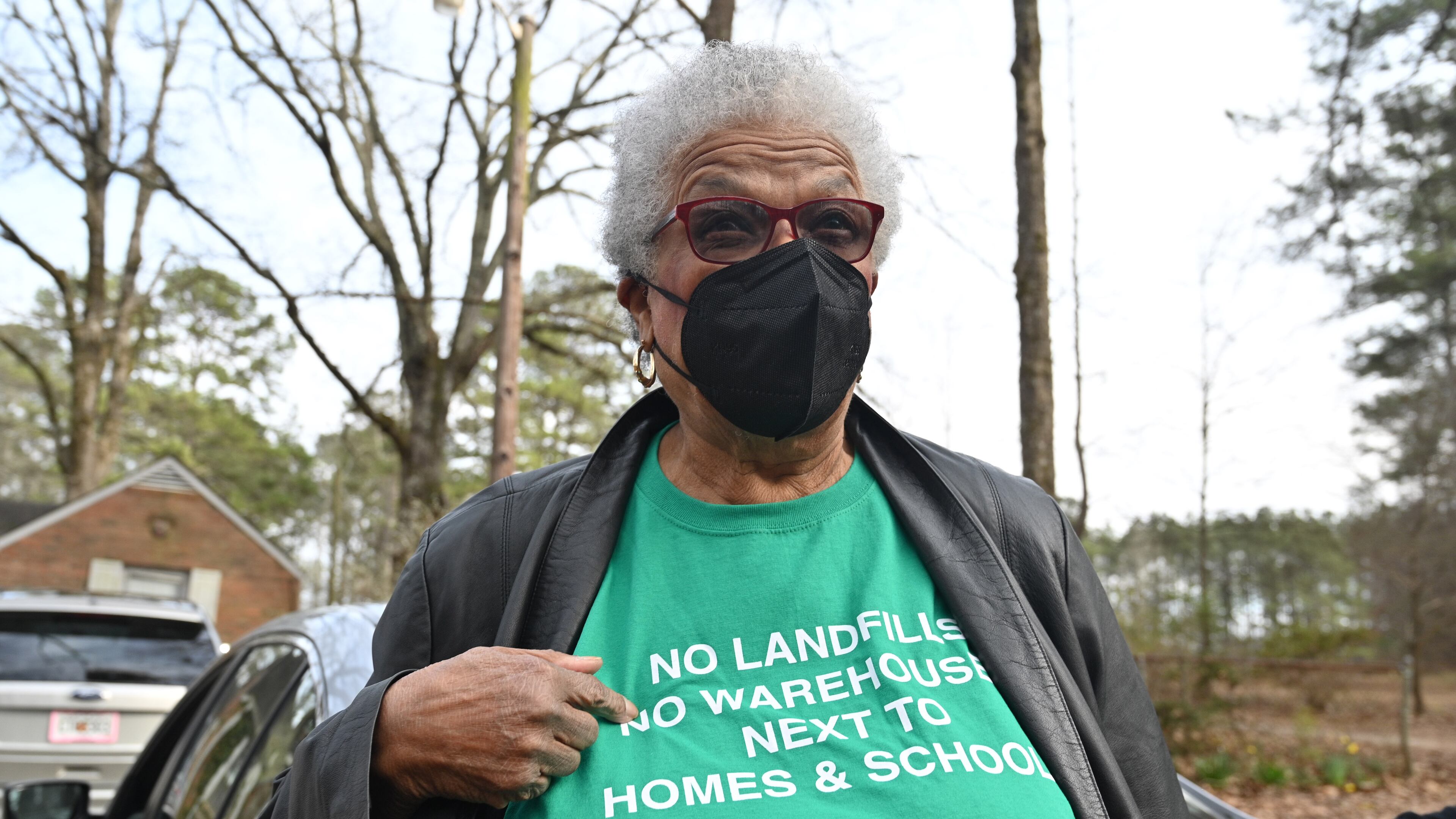

For Naeema Gilyard and other residents of cities in south Fulton County — a mostly Black area west of Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport — the air they breathe has been a worry for years.

Since 2018, an illegal landfill located near homes, churches and two schools has repeatedly caught fire, spewing thick black smoke into the air. Despite investigations by state and federal environmental regulators and multiple judges’ orders to clean up the dump, it remains a nuisance. As recently as last November, smoke was again observed rising from the smoldering heaps of trash.

Then there is fresh anxiety about the distribution warehouses and a major rail terminal that now straddle South Fulton Parkway, and the steady stream of diesel big rigs they’ve brought to the area. Even with modern engines burning cleaner fuel, diesel exhaust is known to contain a dangerous cocktail of air pollutants.

Numerous studies have found Black communities are often disproportionately exposed to air pollution. And while asthma affects many Georgians, the condition is most prevalent among Black residents — especially children. Pollution from roadways and other sources are among the main culprits known to contribute to the disease.

But with only a handful of monitoring sites scattered across the vast Metro Atlanta region, consistent hyperlocal data is often unavailable for those at risk.

It’s a reality that has frustrated Gilyard and others.

“I want the data,” said Gilyard, a former city of South Fulton councilwoman. “I want to know every little piece of what’s going on because it’s been a long time and we’ve been through too much.”

Now, a series of new campaigns and studies aim to provide the data they’ve craved.

In November, the federal Environmental Protection Agency announced it would distribute more than $53 million to support 132 air monitoring projects in underserved communities around the country, including two in the Atlanta area. The money comes from President Joe Biden’s signature climate and health law passed this year and the 2021 pandemic stimulus bill known as the American Rescue Plan.

One of those projects — led by the local nonprofit Environmental Community Action, Inc. (ECO-Action), with support from Emory University and other groups — plans to install new air monitors in at least five communities around the city with longstanding pollution concerns. The area around the city of South Fulton is likely to receive new monitors from the program, said Lynne Young, a program developer at ECO-Action.

Air pollution has been recognized as a serious health threat for years. One of the most dangerous types is PM2.5, a class of microscopic air particles 30 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair. The particles are produced by a host of sources, including fires, construction and vehicle traffic.

Their microscopic size allows them to enter the lungs or even the bloodstream, contributing to tens of thousands of premature deaths in the U.S. each year. The federal Environmental Protection Agency is currently weighing tighter standards, which the agency says are needed to protect public health.

ECO-Action’s monitoring will track PM2.5, but will also gather around-the-clock data on a range of other hazardous pollutants, including ozone and man-made chemicals known as volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

A separate EPA-funded study plans to install monitors at 11 public schools south of I-20 located near interstate highways, one of Atlanta’s main sources of air pollution.

The ECO-Action project is still working to determine final locations for its monitors, but Young hopes data collection will begin this spring. With underserved communities’ pollution concerns not always taken seriously, Young said this information is critical to their environmental justice fights.

“We’re trying to collect data so they can demonstrate that there is a problem,” Young said.

As these new campaigns get off the ground, another study on a potential air pollution solution in Atlanta is nearing the finish line.

For the last two years, Christina Fuller, now an associate professor at the University of Georgia, has explored whether bushes and other roadside vegetation can meaningfully filter the air in neighborhoods near major roadways.

Her team took measurements along the Downtown Connector, I-285 and GA 400 in areas with vegetation, and then compared those levels to measurements taken from roadsides without a shrub or tree barriers. Fuller’s findings are currently under review by a scientific journal.

Fuller said creating vegetative barriers will not bring an end to Atlanta’s air pollution disparities. But she is hopeful her results will offer vulnerable communities evidence to push for solutions.

“Neighborhoods that we know are communities of color next to a highway or a busy road ... the road is there, it’s not going anywhere,” Fuller said. “But if you’re able to plant trees and they can mature over a couple of years, we want to know what kind of protection that would be able to provide for those communities.”

ABOUT THIS SERIES

This year, the AJC’s Black History Month series will focus on the role of resistance to forms of oppression in the Black community. In addition to the traditional stories that we do on African American pioneers, these pieces will run in our Living and A sections every day this month. You can also go to ajc.com/black-history-month for more subscriber exclusives on the African American people, places and organizations that have changed the world.