Atlanta’s Black Streaks reached top of early 20th century motorcycle racing

Bill “Hard Luck” Jones sat near the track at the Atlanta Motordrome, reading his Bible, one Sunday morning in late October 1913.

Jones, one of the best Black motorcycle racers in the South, was mentally preparing to compete in the first event featuring Black riders at the Atlanta Motordrome, a race track made of rough-cut lumber on which motorcycle riders could reach speeds of more than 100 mph.

He was among at least 40 Black motorcycle riders across the country who had elbowed their way into a sport that wanted nothing to do with them.

Board track racing has been relegated to the annals of history. But, a century ago, spectators flocked to Motordromes to watch daredevil feats.

The quarter-mile Atlanta Motordrome had been built in May 1913 by John (Jack) Shillington Prince, a champion cyclist from England. The Atlanta track was one of many such tracks that Prince quickly erected in cities nationwide to accommodate growing interest in a sport that attracted crowds of up 10,000 viewers. White riders for the major manufacturers, such as Indian, Harley-Davidson or Excelsior, could earn more than $20,000 a year, according to Cycle News.

In Atlanta, a group of Black motorcyclists would come to be known as the “Black Streaks,” a reference to the headline of a 1919 article in Motorcycling and Bicycling Magazine. From 1913 to 1924, the Black Streaks were some of the most well-known racers in the nation. The riders had standout nicknames: Hall “Demon Wade” Ware, Horace “Midnight” Blanton, “Bones the Outlaw.”

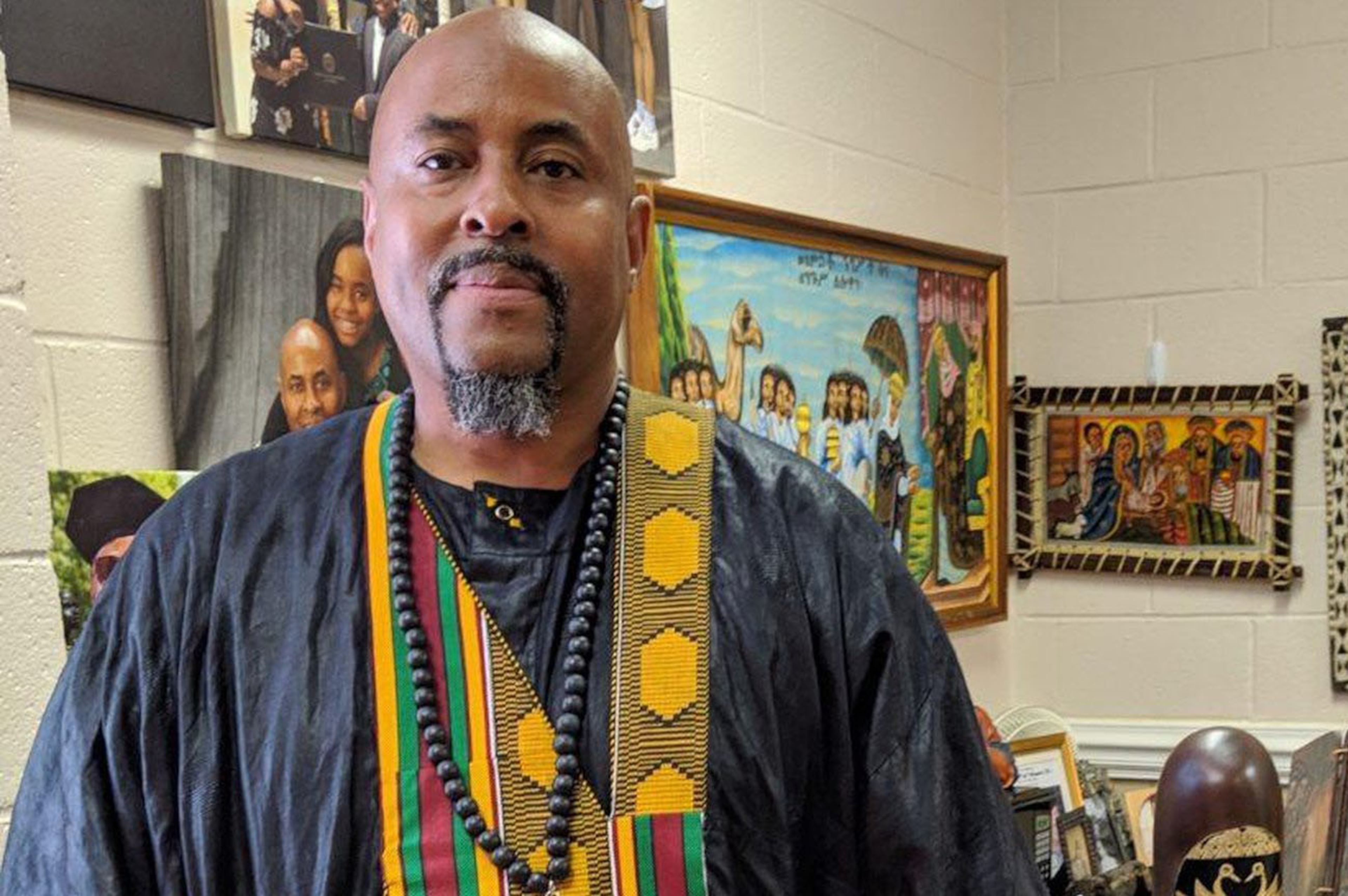

“Not only did they race and make a name for themselves, it is also how they got lost to history,” said vintage motorcycle collector and racer Randy “Detroit” Hayward, who created a traveling Black history museum that includes Black motorcycle riders. Because of those nicknames, “there are people walking around now who don’t know they had a family member who broke barriers,” he said.

Black riders’ challenged social norms but their presence also hastened the demise of motordromes. Racing insiders thought Black participation sullied the sport. In addition, there were inherent dangers that prompted some local governments to close locations.

Successfully navigating the wooden board tracks was often a matter of life or death. Even some spectators were killed when riders lost control. Newspapers began referring to motordromes as “murderdromes.”

David Morrill, a racing historian and racer based in Ocala, Florida, was surprised when he learned more than 10 years ago about the Black Streaks. With assistance from the late Stephen Wright of Morro Bay, California, Morrill used old cycling magazines, photos and stories from The Atlanta Constitution to piece together the history of the trailblazing riders.

The first mention of them came in August 1913, when Jones competed against fellow Black racers at the Atlanta Speedway in a fundraiser for Big Bethel Church, according to reports from The Atlanta Constitution. The Speedway, built by Coca-Cola founder Asa Candler, had been hosting races for white motorcyclists since 1909.

That same month, word spread that the Motordrome was planning a race for Black riders. Motorcycle dealers swiftly condemned the race in the September 5 issue of Motorcycling magazine. “It’s like everything else. The negro tries to copy the white man, like a monkey, and makes a fizzle of it,” said J.D. Aiken, manager of the Southern Motorcycle Co.

Industry dealers had never liked motordrome racing, Morrill said. And the sanctioning body of the sport, the Federation of American Motorcyclists (FAM), reportedly had this as its No. 1 rule: All riders must be white.

Black riders had no choice but to compete against each other and make their own bikes. Dealers wouldn’t sell to them. So they cobbled together bikes using discarded parts that white riders had deemed unsafe and obsolete.

In the September article, a representative of FAM said the Atlanta Motordrome would be outlawed if it held the race for Black riders.

The race was postponed twice due to rain. But, on October 28, Jones competed against Lloyd Brown of Atlanta, the Wilson brothers from New Orleans and Ben Griggs and Willie McCabe of Chattanooga.

Though the race had caused such a ruckus before it took place, no media covered the actual event. The winner is unknown.

Less than a month later, the Motordrome filed for bankruptcy.

“What caused the Atlanta track to go into bankruptcy was they lost their sanction because of the race they held with the Black riders,” Morrill said. The Motordrome would later reopen with new owners.

Before long, motorcycle racing shifted to the one-mile dirt track at Lakewood Speedway, which opened in 1917. The owners revived the races for Black riders as the “Grand Colored Motorcycle Championship Race.”

“Regardless of what FAM said, if someone who owned a track knew it would be empty on Sunday or Thursday ... they were not going to let that money go by the wayside,” Hayward said.

Motordrome racing, said Morrill, had proven to be a bit of a fad. When the novelty wore off in the mid 1920s, Black riders moved on, as well.

Bones the Outlaw had switched to auto racing. Demon Wade had sold his bike and moved North.

In 1924, during what appears to be the final race of the famous Black motorcyclists, Blanton easily beat the less experienced riders.

And the Atlanta Black Streaks faded to black.