Atlanta air quality improved, but still gets an F in annual survey

Metro Atlanta’s air quality has improved significantly over the past two decades, but the area still received a failing grade this year from the American Lung Association for harmful smog.

And experts warn climate change threatens to derail hard-earned progress.

Atlanta ranked as the 51st most polluted city for smog and 37th for year-round soot in the association’s State of the Air report. Atlanta improved 16 places for smog and six places for year-round soot compared to a year ago.

The ALA and state officials attribute the Atlanta area’s improvement to long-term trends related to the federal Clean Air Act, which, among other things, sets standards for air quality and emissions from vehicles and industry.

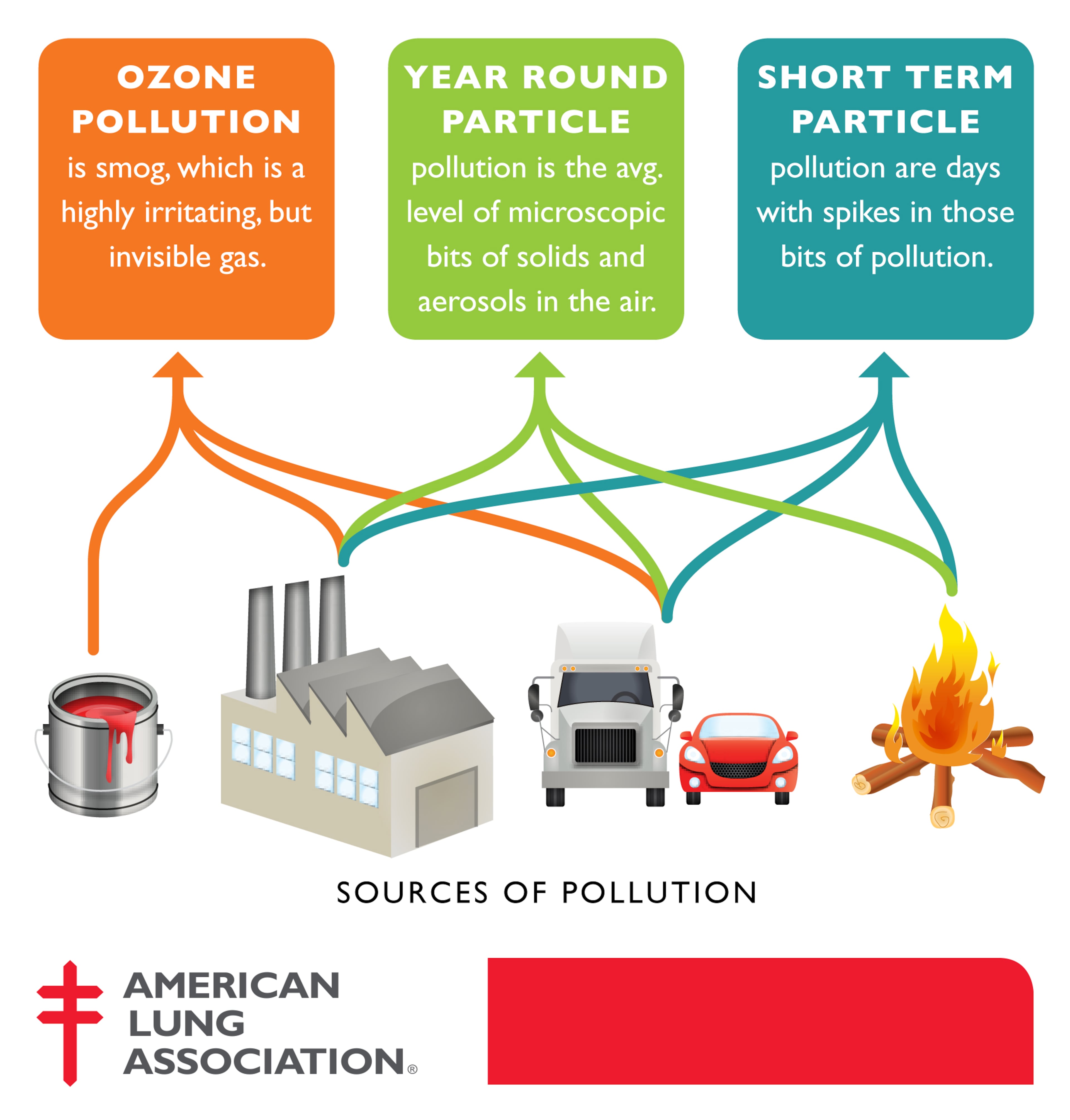

The association’s State of the Air report has been released annually for 23 years and uses data collected by the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It measures two kinds of air pollution: ground-level ozone pollution, otherwise known as smog, and particle pollution, or soot.

Ashley Lyerly, the association’s senior director of advocacy for Georgia, said the data was encouraging but cautioned against complacency.

“The air quality is better, which is great, but it’s still not great,” she said, adding that Atlanta has the fourth poorest quality air in the Southeast.

Karen Hays, the air protection branch chief for the state Environmental Protection Division (EPD), wrote in a statement that that air quality in Georgia has improved dramatically over the years and all areas of the state are meeting the federal standards.

Many sources contribute to air pollution, including emissions from burning fossil fuels in vehicles and power plants. These emissions also contribute to climate change, which exacerbates air pollution by creating conditions that make and trap ozone at ground level. Climate change has also increased the risk of wildfires that spew dangerous soot that can travel hundreds of miles and triggered earlier spring blooms with longer, more intense pollen seasons.

This week, the American Medical Association declared climate change a public health crisis.

According to the ALA, three-out-of-eight Americans — or more than 137 million people — live in parts of the country with failing grades for smog or particle pollution.

Dr. Rabih Bechara, a pulmonologist and professor of medicine at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, said air pollution is especially hazardous for children, pregnant women and people who suffer from lung or heart problems.

“It’s not good for healthy people and it’s definitely not good for people who already have lung disease,” he said. “We see more individuals who have lung cancer these days. We are seeing more children who have asthma these days. ... The presence of these pollutants could potentially be also causing some of these consequences.”

Bechara said that while data was still being collected on the coronavirus pandemic, those who suffer from long COVID are likely to be more vulnerable to air pollution.

Dr. Stanley Fineman, an allergist with Atlanta Allergy and Asthma, also said he has noticed a troubling trend in lung disease over his 40 years practicing medicine in Marietta.

“It’s definitely worsening in terms of we’re seeing more of it,” Fineman said. “We’re seeing a trend for increasing temperatures and the detrimental effects it has on our patients, especially in terms of respiratory health.”

While Atlanta’s air quality improved, Augusta’s worsened, pushing Georgia’s third-largest the city into the top 25 worst cities for year-round particle pollution. Hays, the state EPD official, attributed the decline to fires in the Augusta area, as well as fireworks that were set off near an air quality monitor and newer, more sensitive equipment.

Nationally, wildfires are driving a widening disparity in air quality between the Western and Eastern halves of the country, the ALA found.

Overall, the ALA report found that Americans experienced the most days of “very unhealthy” or “hazardous” air quality since the report began tracking it. The three years covered by the report ranked among the seven hottest years on record globally, it added.

In addition to regional, geographic disparities in air quality, the report also found racial disparities. People of color were 61% more likely than white people to live in a county with a failing grade for at least one air pollutant, and more than three times as likely to live in a county that failed for all the pollutants measured by the report.

Georgia publishes daily pollution readings at airgeorgia.org and vulnerable people can reduce exposure by staying inside on days with poor air quality. The National Weather Service also publishes a daily air quality forecast.

But individuals can only do so much, especially as Georgia’s cities grow in population and the number of cars on the road, Bechara said.

A note of disclosure

This coverage is supported by a partnership with 1Earth Fund, the Kendeda Fund and Journalism Funding Partners. You can learn more and support our climate reporting by donating at ajc.com/donate/climate/