How do American youth become neo-Nazis?

Facebook discussion: The AJC is moderating a respectful discussion of what should happen next with Confederate monuments in the South: should they be removed, left alone or augmented with text that provides more context about the person depicted in the monument? Like to join? Write to us at race@ajc.com, and we'll extend an invitation.

Shannon Martinez’ hair hangs just below her shoulders these days.

It’s a radically different look from the one she cultivated 25 years ago – when she wandered the country as a teenage skinhead.

“Growing up, I was the black sheep in my family. I never fit in,” said Martinez, now 43. “I hated everybody. To be a part of a hate group, all I had to say was ‘I hate black people, I hate Jews and I hate non-whites.’ That was the price of admission. I was a white-power skinhead.”

» Andy Young: Don't blame uneducated white people

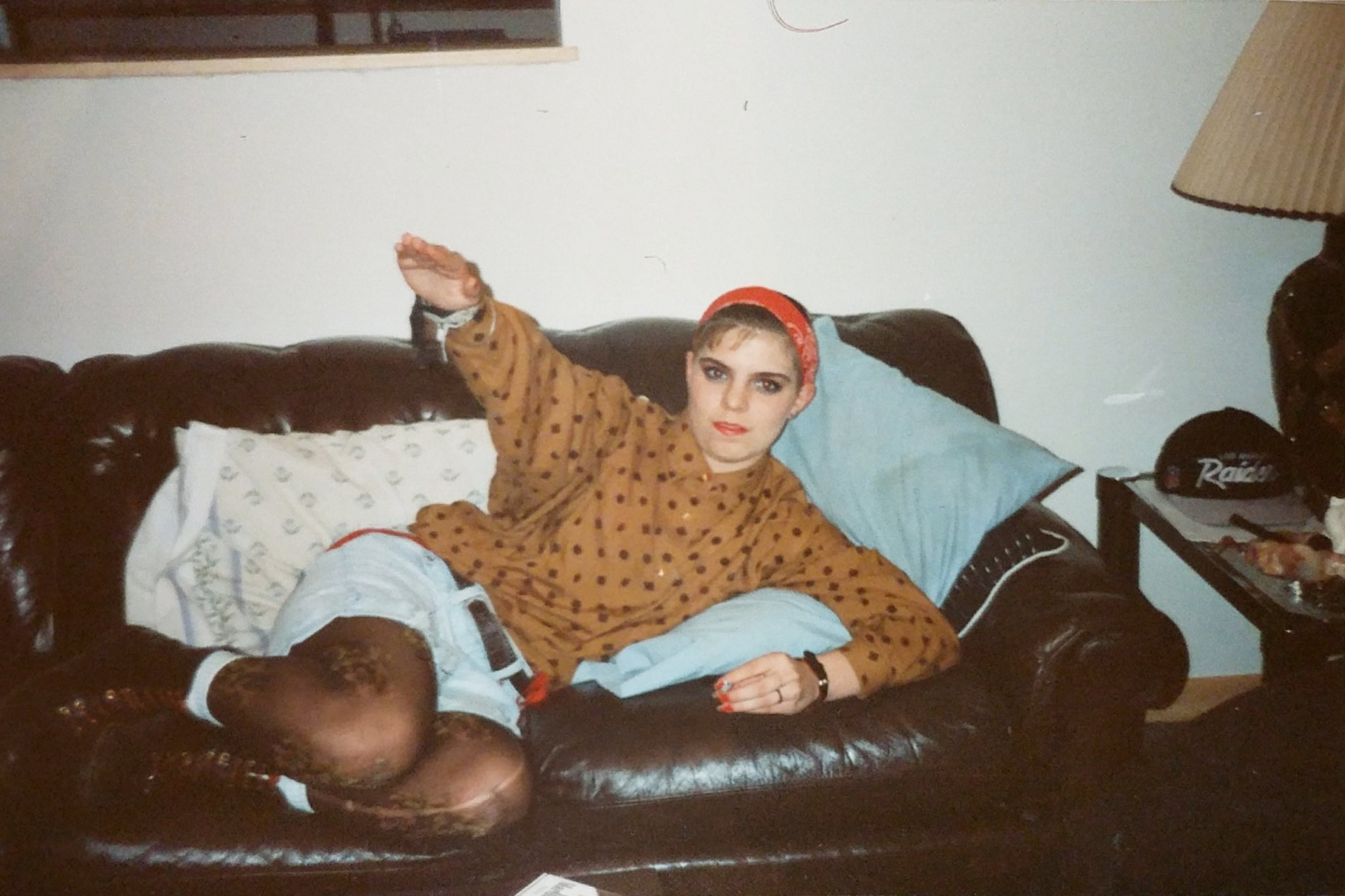

She picks up a photograph of herself taken in 1990 with a friend. She is about 16. Her head is shaved, except for a tuft of bangs in the front. The two are standing in front of a Confederate flag and giving the Nazi salute.

“I look at this and see so much hurt in my eyes,” Martinez said last week. “Almost a blankness. I can see the pain.”

» 2,000 march in downtown Atlanta over the weekend

Experts who study hate groups say that many young people turn to neo-Nazi or Klan factions because they have few other options. Finding young adulthood a big, empty place, they are readily radicalized by hate groups that offer a sense of identity and belonging. Many white supremacists share an ironic bond with American Islamists: They are not indoctrinated by radical far-right parents so much as they are seduced by the Internet.

“Members do seem to be getting younger and while there are a number of reasons people join, it often seems to be filling a void in their lives,” said Paul Becker, a sociology professor at the University of Dayton who has written extensively about hate crimes, white supremacy and anti-government movements. “So these groups provide a place to belong, friends, and give their lives a goal or purpose. Therefore, something like coming from a broken home or experiencing abuse could be a factor in someone joining these types of groups.”

‘There is no new racism’

In that long-ago photo, Martinez is dressed in a blue flannel shirt and black pants, with an iron cross draped around her neck.

On this day, she is wearing a bright white sun dress. It has birds and flowers on it.

The skinhead years were a long time ago. But with the images coming out of Charlottesville last weekend, the threat of more racially inspired protests and violence on the horizon, and the tepid response from the White House, those years don’t seem quite so distant.

With the face of racist extremism seemingly getting younger, Martinez is one of the lucky ones. She got out and now she is trying to pull others out by working with an organization dedicated to helping people repudiate white supremacy.

“There is no new racism. There is no new dark place or uptick in racism,” Martinez said. “But there is a pendulum dynamic. When one end of the political spectrum is given more voice and credence, there is always a backlash. It has become easier for those people to come out in the open because of the climate created since Trump became a viable candidate.”

‘I felt sad, angry, guilty, helpless’

Last Sunday, the pendulum — some say it was set in motion with the election of Donald Trump – swung far to the right. Led by the likes of alt-right lighting rod Richard Spencer, hundreds of white supremacists — neo-Nazis, skinheads, Klansmen — descended on Charlottesville to protest the proposed removal of a Confederate statue.

Counterprotesters also showed up. That is when 20-year-old James Alex Fields Jr., who has been described as a Nazi sympathizer with a “fondness for Adolf Hitler,” rammed his car into a crowd of counterprotesters, killing Heather Heyer, 32, and injuring 20 more.

“I knew what was going to happen because it is exactly what I was actively working to make happen more than two decades ago, when I was involved in the violent far-right,” said Angela King, a co-founder of Life After Hate, a national organization designed to help neo-Nazis and other white nationalists find a path away from hate. “I can’t begin to fathom how it must have felt for Holocaust survivors or other survivors of dehumanization and violent extremism. I felt sad, angry, guilty, and helpless.”

» Photos: Confederate monuments in Atlanta

In responding to the events, Trump blamed both sides for the confrontation and said there were good people among the protesters. The president later tweeted that Confederate statues should not be removed.

Robbie Friedmann, founding director of the Georgia International Law Enforcement Exchange at Georgia State University’s Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, said he is troubled by the notion of “political equivalency” for either side of the argument.

“There is no room for an ideology that preaches hate,” Friedmann said. “If this picks up momentum, there is a real danger of increased violence. That needs to be nipped in the bud, because we are just on the cusp of this. What concerns me about what is happening in Charlottesville is, it is moving from rhetoric to physical violence, which is reminiscent of the 1930s.”

‘They are using Twitter and Instagram’

If the face of hate in America is growing younger, the mechanics of hate have grown more sophisticated.

While some old-school Klan members are content with passing out fliers, and the skinheads might seek recruits by instigating a brawl at a club, younger extremists are seeking members where they hang out – on websites and social media.

They are attracted to crude video games on racist sites; for example, a “Nazi Pac-man” game in which a German soldier gains power by consuming swastikas and then destroys Jewish “monsters” (a Star of David flies off the board when a monster is defeated). And there’s a new tool of recruitment: memes and trolls on sites such as 4chan, 8chan and Reddit, said Marilyn Mayo, senior research fellow at the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism.

This younger group found it easy to trigger shocked reactions with Holocaust memes and bigoted humor, and took delight in doing so. Organizers like Spencer and Andew Anglin, editor of the neo-Nazi online publication Daily Stormer, saw the potential in trolling and began encouraging the young white males to meet in person, Mayo said.

“They are using Twitter and Instagram,” said Andrew Selepak, a University of Florida professor who wrote his dissertation on how the Ku Klux Klan uses the internet to spread its message and recruit new members. “So you don’t have people involved in that who are showing up and paying dues. They are just participating in something.”

Martinez agrees that one of the attractions to these groups, like traditional street gangs, is the sense of family and acceptance. But she disagrees that members and followers are getting younger.

“They might be getting more educated. If you look around the globe and the extreme wings, you always find a very large percentage of young adults. More them are in college and of college age,” Martinez said. “The thinking was, rather than shaving your head and getting tattoos, the best way to mobilize was to go to college, join the police force, go into the military and look like everyone else to infiltrate society and be more effective as an agent for change. Instead of looking like a street thug. You look at these young men and they don’t look scary.”

‘They are sharp and intelligent’

One man who was not impressed by these self-styled Nazis was Byron “Delay” De La Beckwith Jr., the son of the notorious Mississippi Klansman convicted of assassinating the NAACP’s field secretary Medgar Evers in 1963.

An unapologetic member of the KKK himself, the younger De La Beckwith was the subject of a 2012 documentary, “The Last White Knight,” a movie that premiered at Atlanta Jewish Film Festival.

The young men recruited for the march in Charlottesville are the dim-witted victims of propaganda from such men as New Orleans Klansman David Duke, said De La Beckwith. "You take 100 of them, they can't tell you who the first president of the United States of America was. I bet they can't tell you anything about John F. Kennedy."

“The ones that are organizing this and putting it together, they are sharp and intelligent and are manipulating the truth to their advantage.”

That is what attracted Martinez in 1989, who could never live up to her parents exacting standards and began to subtly drift.

‘The anger and rage began’

An athlete growing up, her family moved to Michigan in 1985. It was right on the border of Ohio, and Martinez went to a private school in Toledo. State rules prevented her from playing sports.

With no sports, she gravitated to the skateboarding crowd. Then to the punk rockers, whose culture overlapped with skinhead groups. When she was 15, two men raped her at a party.

“That would really seal the deal about where I was going,” she said. “The anger and rage began to eat away at me. There was a sense of not feeling like I belonged. A self-loathing.”

Skinheads gave her an angry sense of hope.

“These people had my back and they liked to fight,” Martinez said. “I could have gone anywhere in the country and because I knew the lingo, wore the clothes and had the tattoos, I was identified as someone who belonged.”

In 1992, she was taken in by the mother of a skinhead boyfriend in Houston.

“She knew I was a skinhead, because I looked the part,” said Martinez, adding that her then-boyfriend was away in the Army. “But she took me in and accepted me.”

The woman dragged Martinez to Cub Scout meetings and had her babysit and read to her children. She joined in on camping and fishing trips.

“She would talk to me about my future. She encouraged me to get a GED and go to college,” Martinez said. “It was not sudden, but here is this person pouring out underserved love and compassion to me. I began to see value and participate in the future. I ended up back home and in college.”

By the time she was 19, Martinez had abandoned life as a white supremacist.

‘Imagine what we could accomplish’

Recently, she started working with Life after Hate, which was founded by her old friend Christian Picciolini — the same friend who appeared in the Nazi-salute photo with Martinez more than a quarter-century ago. The organization was promised a nearly a half-million dollars in grants from the Obama administration, but in June, the Trump administration slashed funds from organizations dedicated to fighting right-wing violence, including Life After Hate.

“We operated for more than four years on the hundreds of volunteer hours our team put in and whatever resources we could scrape out of own pockets,” said Angela King, the organization’s deputy director and former skinhead who spent three years in prison for robbing a Jewish-owned store. “Imagine what we could accomplish with funding.”

In her Athens home, where she homeschools her seven children, Martinez is not too worried about her children following her early footsteps, which they know all about.

“They are being raised to be philosopher-kings and empresses,” she said. “We are all very close-knit and have good strong relationships. We engage purposely in conversations. We are committed to talk about everything.”