As Atlanta grows, its trademark tree canopy suffers

At the back of a narrow dirt lot in Reynoldstown where a small bungalow once sat, three trees stood behind an orange plastic safety fence.

The trees — two water oaks and a pecan — have shaded the neighborhood for between 45 and 70 years, said Greg Levine, the co-executive director of the nonprofit Trees Atlanta. An investor bought the property in 2020 and on a recent Thursday, an orange “X” spray painted across each of their trunks indicated the trees likely would not stand much longer.

In popular neighborhoods like Reynoldstown, Levine said, investors can score big pay days with zoning that allows older homes to be replaced with new, larger ones. Often, that redevelopment comes at the expense of the city’s famed trees.

Atlanta’s canopy remains among the most intact of any major U.S. city, emblematic of its “city in the forest” moniker. But analyses commissioned by the city and new data show Atlanta’s trademark canopy is in decline.

A 2018 survey conducted by Georgia Tech researchers found the city’s canopy had declined by roughly 1.5 percentage points from where it stood in 2008, with close to half an acre of trees lost each day over that time.

Scientists say tree cover is vital to public health. Climate change-fueled heat waves and floods are increasing in intensity and frequency, and trees are among the best ways to build resilience in urban environments.

But data from the city’s arborist division analyzed by The Atlanta Journal Constitution shows tree removals — both legal and illegal — along with those classified as dead, dying or hazardous, have exceeded the number of trees replaced each year since mid-2013, coinciding with a post-Great Recession development boom.

The pace of canopy decline has surged the last two years. The period from July 2021 to June 2022 saw nearly 24,000 trees cut down or tabbed for removal and almost 19,000 in the year prior. Those years are the top two for removals in the last nine years.

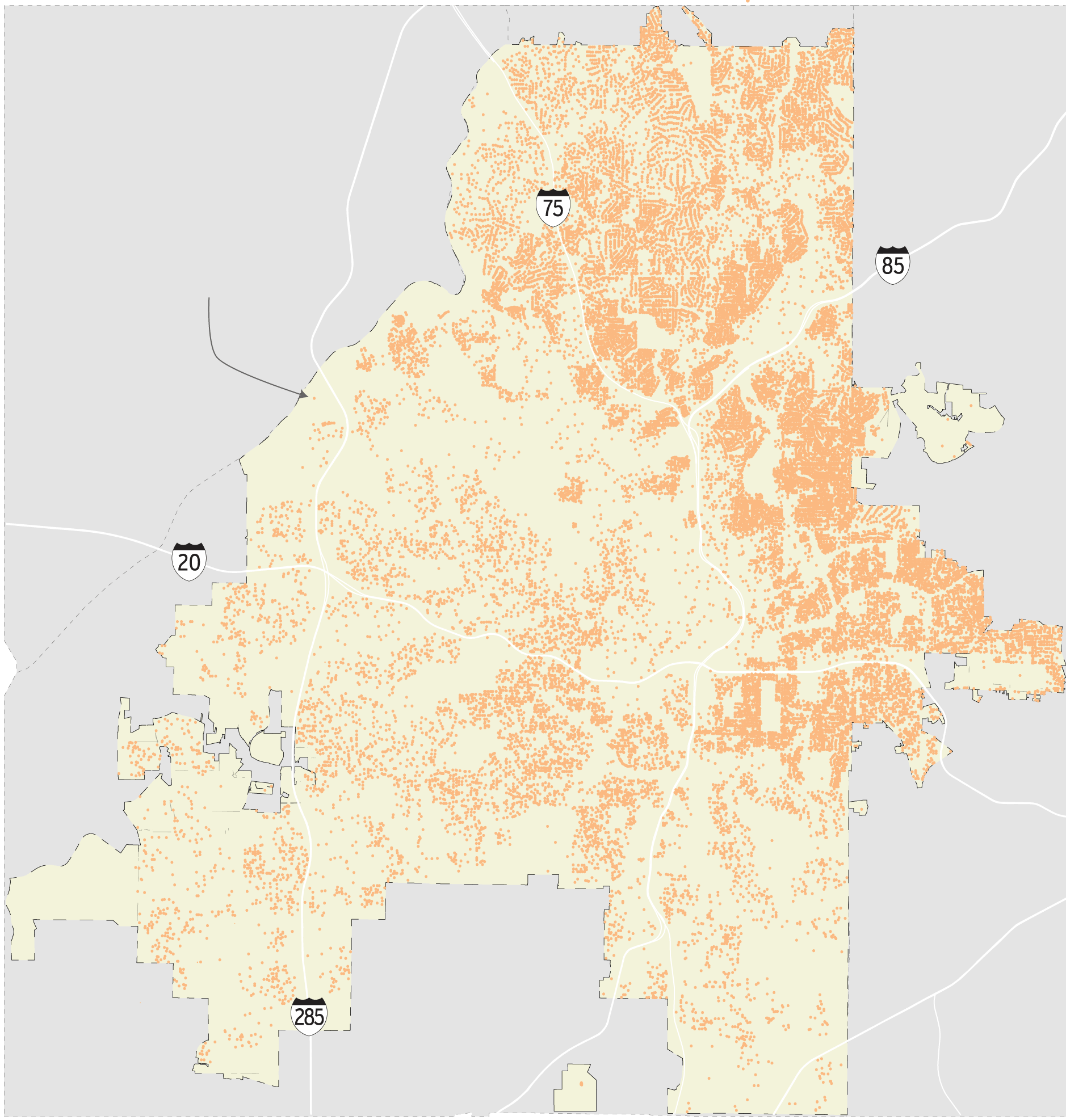

Since 2009, city data shows permitted tree removals in Atlanta have been concentrated to the north and east of downtown.

One dot indicates

a tree approved for

removal.

Source: City of Atlanta

The city imposes a $500 fine for illegal cuttings, which escalates to $1,000 for each additional violation. Still, illegal removals hit a new high of more than 1,200 last year, almost double the previous record. The city says it’s difficult to pinpoint a reason for the increase, but attributed it, in part, to the explosion in building and new tree companies, some of which aren’t well-versed in the rules.

Those illegal removals are likely an undercount.

“I was really concerned 10 or 15 years ago,” Levine said. “Now, I think we’re beyond the critical time.”

Meanwhile, Atlanta’s tree ordinance — the complex rules and regulations that govern tree removal and replacement — has been left mostly unchanged for more than two decades.

Efforts to update the ordinance have stretched across three different mayoral administrations, but have largely failed. Last month, City Council succeeded in passing modest changes, including new rules for tree plantings in parking lots and on streets.

More significant and controversial matters — like the cost to remove a tree and how much of Atlanta’s canopy should be kept intact — were not addressed.

City Councilman Jason Dozier, who represents parts of downtown and neighborhoods south and west of the city center, is leading the current push to revise the ordinance. He said he hopes to introduce legislation that tackles those issues and more early this year. But if history is any guide, balancing the demands of conservationists and developers will be difficult.

“We’ll get something done,” Dozier said. “It’s absolutely critical that happens.”

Ordinance rewrites fizzle

Along with Atlanta’s Piedmont Park, Westside Park and other green spaces, the city has purchased hundreds of acres of forest southeast and southwest of downtown to preserve its canopy.

Still, the vast majority of Atlanta’s tree cover is on private, residential property. The 2018 assessment by Georgia Tech researchers found that around 84% of the city’s canopy is on land zoned for single or multi-family residences, making it vulnerable to development.

The tree ordinance isn’t the only way to protect trees, but it is “a critical piece of legal infrastructure,” said Brian Stone, a professor of environmental planning at Georgia Tech.

Atlanta’s current ordinance has been in place since 2001. Before updates were passed in December by City Council, the last changes came around the time of the Great Recession. A subsequent housing boom and a youth-driven influx of residents back to intown neighborhoods have occurred in the years since.

Decatur and Brookhaven both updated their ordinances in the last two years, but Atlanta’s efforts have lagged, with a pair of rewriting efforts stymied since 2014.

Few elected officials have been involved in the tree ordinance saga longer than Councilwoman Mary Norwood, now in her third stint and representing Buckhead’s District 8. Norwood said in the past, the divergent views of tree advocates, developers and other groups have been insurmountable.

“When you have competing interests, it’s very hard to make something understandable enough that the council will say, ‘We are drawing the line in the sand and we’re going to pass this because it’s the right thing to do,’” Norwood said.

One of the thorniest parts of the ordinance is recompense: In short, how much it costs to cut down a tree.

The city currently places a price tag of $100 on each tree, with $30 added on for each diameter inch of trunk. Fees can be capped in certain cases, depending on the zoning and type of development.

Tree advocates and City Hall staff say penalties are too puny to discourage clear cutting or fund tree replacement and forest acquisition.

In a statement, the Department of City Planning said they support raising recompense to match the “market rate” that would allow the city to plant replacement trees.

Developers, however, say a steeper fee will have consequences, such as increasing housing costs.

“When you talk about affordability ... increasing recompense or any type of fee is just going to be adding to the cost of construction and the cost of doing business,” said Joseph Santoro, the director of policy and government affairs with the Council for Quality Growth, a development industry trade group.

Kathryn Kolb, a conservationist who leads one of several groups pushing to modernize the ordinance, says those concerns are overblown, and that the city can protect trees and keep the cost of living down if it focuses on density.

“If you tear down a small house and put up a much larger house and clear that whole lot, we haven’t gained any density,” Kolb said. “We’ve eliminated half-an-acre of trees, but we are not housing any more citizens.”

As trees fall, Atlanta gets hotter

Atlanta’s trees are part of the city’s identity, but experts say there are other reasons for preserving its canopy.

Like many other urban areas, Atlanta is getting hotter due to human-caused climate change. Annual average temperatures in the city have risen about 3 degrees since 1930, according to National Weather Service data.

Heat waves — a stretch of two or more days with abnormally warm temperatures — are also becoming more frequent and intense. Federal data shows Atlanta experiences around six more heat waves each year today than it did in the 1960s. Extreme heat is not just uncomfortable — it can also be lethal. Heat waves are among the world’s deadliest natural disasters.

In Atlanta, heat-absorbing buildings and roadways can create urban heat islands that are much warmer than surrounding areas.

“Tree canopy is really the principal variable that governs how rapidly the city is heating up,” Georgia Tech’s Stone said.

Vegetated areas also provide a measure of defense against flooding, another extreme weather event made more common and destructive by climate change.

“Trees enable urban soils ... to absorb more water,” reducing runoff that can overload streams and trigger flooding, Stone said.

Can Phase 2 succeed?

After past efforts at a full revamp of the ordinance sputtered, City Council is using a phased approach this time. But the Phase 1 updates passed in December were largely changes on which tree advocates and developers agreed.

Now comes the hard part.

In addition to recompense, tree advocates say the Phase 2 overhaul must set a goal for how much remaining canopy the city wants to save.

The 2018 canopy survey found the city’s coverage had declined to 46.5%. Experts say it has likely shrunk since then.

Any target must be achievable, said deLille Anthony, a community advocate who co-founded the grassroots organization The Tree Next Door.

“My feeling is let’s be real,” Anthony said. “Don’t set these goals that you have no way of meeting.”

The tree ordinance won’t fix all that ails Atlanta’s canopy.

Zoning regulations set the maximum percentage on residential lots that can be covered by impermeable surfaces. But there are no restrictions on how much of a lot can be dug up to build a house.

Advocates say entire lots are often graded, damaging trees and leading to unnecessary removals. With most of Atlanta’s canopy on residential property, they say rules to limit lot disturbance are critical.

Such regulations don’t seem palatable to developers.

Asked whether the city supports zoning changes, the planning department said in a statement it could help preserve trees, but that there have been “significant concerns expressed about that sort of restriction.”

Kolb and other conservationists say the clock is ticking for the city to act.

“If we take away our canopy, Atlanta is going to be a very hot, uncomfortable place to live,” Kolb said.

A note of disclosure

This coverage is supported by a partnership with 1Earth Fund, the Kendeda Fund and Journalism Funding Partners. You can learn more and support our climate reporting by donating at ajc.com/donate/climate/