As a German firm exits the city, downtown Atlanta ponders its future

A German firm caught Atlanta’s real estate world off guard seven years ago when it began buying dozens of empty and boarded-up downtown buildings with a plan to revive them with new restaurants, shops, offices and residences.

Stocked with what was described as patient investor funds, Newport RE set about building a community it dubbed South Downtown, aiming to restore what disinvestment and neglect had taken from one of the oldest parts of the city.

If Newport’s emergence as a downtown power player was unexpected, its sudden exit was downright shocking. Last month, the company said it was selling its entire Atlanta portfolio straddling blocks of Peachtree, Mitchell and Broad streets to Atlanta developer Braden Fellman Group. Economic pressure from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the pandemic’s upending of commercial real estate and difficult financial markets forced its hand, Newport said.

Since COVID-19 hit, some of downtown’s marquee projects have faced significant challenges.

Underground Atlanta’s planned redevelopment was rebooted under a new owner. Newport is almost out the door. The developer steering Centennial Yards, the transformation of what was known as the Gulch, is plowing ahead but also rethinking the need for so many offices as corporations cut costs. And the uncertainty of what comes next for downtown has left longtime residents wondering whether their dreams for a bustling city center will ever become a reality.

“Some of us are surrounded by surface parking lots and empty promises of developments past,” said Kyle Kessler, an architect and downtown resident.

Andrew Braden, principal of Braden Fellman, said he hopes to continue to collaborate with the Newport team and aims to bring the vision of a bustling South Downtown to life.

“Our work in Atlanta over the past four decades has been highly focused on creating residential opportunities in some of Atlanta’s oldest neighborhoods,” he said in an email. “This is no different — and the neighborhood needs more people living in it.”

Atlanta boosters still express confidence in downtown’s rebound, while also acknowledging the wrenches thrown into best-laid plans.

Michael B. Russell, the CEO of H.J. Russell & Co. which worked on landmarks including Mercedes-Benz Stadium and the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, said the sale will delay South Downtown’s timeline.

“I think that area will eventually do well, but this is no doubt a setback,” he said.

Atlanta’s historic district

Downtown is the beating heart of conventions, pro sports and the city’s tourism industry. It’s also home to local, state and federal agencies and Georgia State University. But its office buildings are older and many corporations over the years have left, lured by newer towers in Midtown, Buckhead and along the Beltline.

Downtown also has lagged in residential growth. Nearly 1,000 apartment units are in the construction pipeline downtown, but that pales in comparison to Midtown and east Atlanta, according to real estate consulting firm Haddow & Company.

Over the years, Georgia State has stitched together a modern urban campus from a hodge-podge of old buildings. While that’s brought some stability, downtown needs more than the cycle of college semesters and transient students. It needs permanent residents.

Egbert Perry, the CEO of longtime Atlanta developer Integral Group, said downtown has suffered from years of disinvestment, and putting housing in the city center “was a totally foreign concept” for decades due to concerns about crime. In 1989, Atlanta’s violent crime rate was double that of New York City, though violent crime rates are much lower today.

Perry said there’s hope, pointing to Midtown’s evolution from a derelict district decades ago into what’s now one of the most expensive places to live in Atlanta.

“Some very thoughtful businesses and civic people were saying that we need to make some investment in Midtown to turn the tide,” he said.

Getting people living and working again in South Downtown was the cornerstone of Newport’s plan. The firm has a reputation for buying, renovating and holding urban streetscapes, funding itself with the retirement savings of well-heeled families. That kind of patient investment capital, experts say, is a pre-requisite for tackling a challenge like this South Downtown.

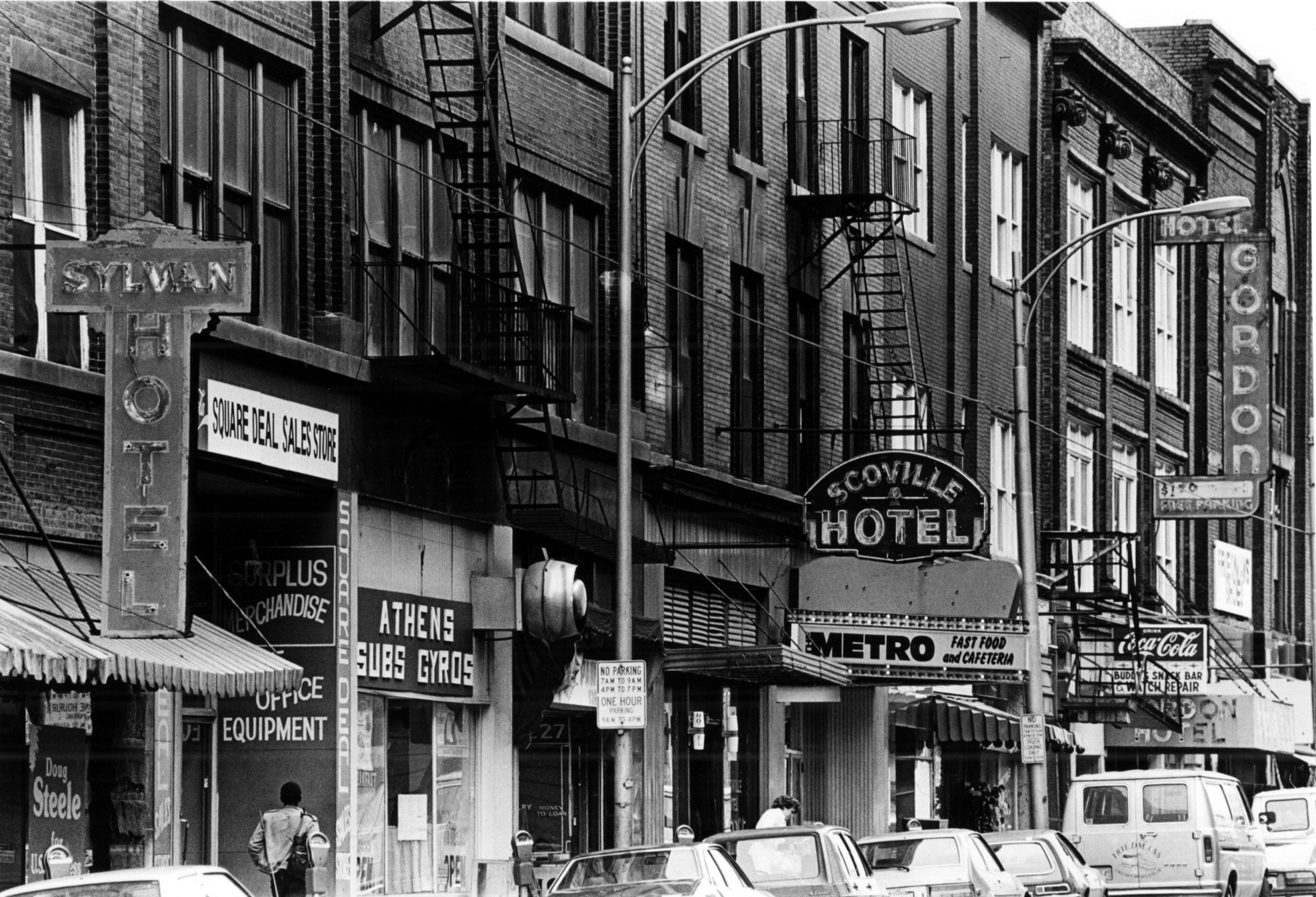

The Five Points area was once the city’s financial district. Decades ago, it was home to two intercity rail terminals — Atlanta Union Station and Terminal Station. Before both were razed, Kessler said the stretch along Mitchell, Broad and Forsyth streets supported a variety of haberdasheries, department stores and hotels, while the upper floors housed lawyers and doctors.

Over the decades as metro Atlanta spread out, downtown’s population slumped. Corporations moved, and many storefronts of South Downtown emptied.

Jake Nawrocki, who opened Newport’s U.S. office, said he saw potential in the neglected buildings and an opportunity to create a district with unparalleled character. Rather than raze and pave, he aimed to convert the inert.

“You’d be the historic district of Atlanta,” said Nawrocki, who left Newport in 2019 to form his own firm, Anvil RE.

South Downtown’s centerpiece emerged on Mitchell Street. There, Historic Hotel Row, a block of early 20th century buildings would become restaurants and shops. And 222 Mitchell, a mid-rise former bank headquarters, would become refurbished offices and a rooftop lounge.

Downtown has roughly 18 million square feet of office space, most of which was built between the 1960s and 1980s during the region’s heyday. When Nawrocki was helming Newport’s project, downtown office demand was increasing as metro Atlanta’s economy boomed, and the firm banked on 222 Mitchell as a safe bet.

“Downtown was the release valve for Midtown,” he said. “They were looking to escape the high office rents of Midtown.”

Pandemic cracks

But when the pandemic shut down offices and led to a rise in remote and hybrid work schedules, urban business districts like downtown were the hardest hit.

In the past three years, many employers slashed office space. The Federal Reserve, meanwhile, has hiked interest rates to tame inflation, making it more costly to borrow and leading companies to shelve expansions. Banks also are pumping the brakes on real estate loans, amid a gloomier picture for commercial landlords.

Office vacancy soared. Nearly 27% of downtown office space is either vacant or on the sublease market, according to real estate services giant CBRE. Midtown and Buckhead also have about 30% office availability, but both submarkets feature newer buildings with more amenities that experts expect will refill more quickly.

Despite economic headwinds, Newport continued to expand its holdings as recently as last year, adding four new buildings and a surface lot along Broad and Mitchell streets. The firm stuck with its office plans for 222 Mitchell, but the project stalled this year.

Hotel Row saw its first restaurant, TydeTate Kitchen, open in April, but other tenants are in limbo or have canceled their plans.

Pins Mechanical Co., a game bar and dining concept, terminated its lease after several delays, a representative said. Both a pizzeria and a rooftop restaurant and cocktail lounge from Slater Hospitality, the team behind Ponce City Market’s Skyline Park and 9 Mile Station, “are still in flux,” according to the company’s co-founder and chief creative officer Mandy Slater.

Newport wasn’t alone in facing challenges downtown.

Underground’s new owners have added the Masquerade and other nighttime hot spots, and its First Friday events have proven popular. But vertical development remains elusive.

Underground terminated the lease of a previously announced Atlanta Brewing Co. taproom last month, citing stalled construction. Developer Shaneel Lalani said a proposed residential tower was also delayed and won’t begin work until interest rates decrease.

CIM Group, the Centennial Yards developer, last year finished the transformation of the former Norfolk Southern headquarters on Ted Turner Drive into 162 apartments that CIM says are more than 93% leased.

CIM opted against launching a new office tower last year, pivoting instead to a 300-unit apartment tower, citing market forces.

It’s also clear that Newport’s problems were not solely about conditions in Atlanta. Newport CEO Olaf Kunkat said global factors including the pandemic, war and interest rate hikes led Newport and its investors to “reprioritize capital investments.”

April Stammel, Newport’s senior vice president, said the bulk sale helped avert a potential worst-case scenario.

“This could have gone into multiple foreclosures and landed at the courthouse steps under auction,” she said in a video on South Downtown’s Instagram page. “None of us here felt like that was the right thing for the neighborhood.”

‘Dedication to a craft’

Braden Fellman, while smaller than giants like Newport and CIM Group, has earned a reputation for converting challenging and historic properties into homes.

The firm, which expects to complete the purchase by year’s end, was among 30 to show interest in Newport’s portfolio, but it stood out among the crowd for dozens of adaptive reuse projects since its founding in 1981. One change Braden Fellman plans is to turn 222 Mitchell into housing.

Aziz Palas owns Sunrise Fragrance, a shop at 191 Mitchell Street. He was optimistic about Newport’s plan and hopes Braden Fellman keeps South Downtown on track.

“The vision Newport had, I’d like to see them continue it,” he said.

David Mitchell, executive director of the Atlanta Preservation Center, said Braden Fellman has converted several factories and warehouses into roughly 2,500 residences across the city. Mitchell added that the firm managed to get two projects on historic registries in recent months.

“That’s a pretty good track record, particularly in this day and age,” he said. “That’s post-COVID and post-all-of-our-problems, staring into the abyss of the problems of the future. Yet, here is stark evidence of a dedication to a craft.”

Russell of H.J. Russell said developers of long-term megaprojects must have patient investors, since it can take several years before developments in up-and-coming areas turn a profit.

“This is not a build it and flip it kind of mentality,” he said. “You have to have some staying power and some vested interest in the area.”

The restart to South Downtown comes as downtown boosters look for ways to convert other older towers into residential. Brian McGowan, head of Centennial Yards, said Newport deserves “a lot of credit” for seeing downtown’s potential.

“No one should see this as a signal that there’s something wrong with downtown,” McGowan said. “It remains a great place to invest, and it’s definitely where the economic center of gravity is shifting in Atlanta.”

Editor’s note: This story has been update to clarify the termination of lease for a planned taproom at Underground Atlanta.