A look back at how Watergate scandal began

Forty-nine years ago Thursday, five burglars were arrested inside the offices of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate office complex in Washington. The arrests would set off a chain of events that would dominate the news for the next two years and lead to the first resignation of a U.S. president. Here’s a look back at June 17, 1972.

The location

The Watergate Office Building was part of a six-building complex constructed along the Potomac River from 1963 to 1971 that included offices, a hotel and apartments. The DNC’s offices were located on the sixth floor.

The break-in

The first story in The Washington Post began this way:

“Five men, one of whom said he is a former employee of the Central Intelligence Agency, were arrested at 2:30 a.m. yesterday in what authorities described as an elaborate plot to bug the offices of the Democratic National Committee here.”

The plot had been devised by G. Gordon Liddy, a leader of the White House “plumbers” unit set up to plug information leaks and a strategist for President Richard Nixon’s reelection campaign.

Liddy, a former FBI agent, and E. Howard Hunt, a former CIA agent, engineered two break-ins at the Democratic National Committee offices in the Watergate in 1972. On May 28, as Liddy and Hunt stood by, six Cuban expatriates and James W. McCord Jr., a Nixon campaign security official, went in, planted bugs, photographed documents and got away cleanly.

A few weeks later, on June 17, four Cubans and McCord, wearing surgical gloves and carrying walkie-talkies, were arrested when they returned to the scene to fix problematic bugs from their first visit.

Liddy and Hunt, running the operation from a Watergate hotel room, fled but were soon arrested and indicted on charges of burglary, wiretapping and conspiracy.

In the context of 1972, with Nixon’s triumphal visit to China and a popular presidential campaign that soon crushed Democrat Sen. George S. McGovern, the Watergate case looked inconsequential at first. Nixon’s press secretary, Ron Ziegler, dismissed it as a “third-rate burglary.”

The guard

The burglary was discovered when Frank Wills, a 24-year-old security guard at the Watergate offices who was working the midnight shift, discovered tape over a lock on a basement door. Thinking some worker had left it to make it easier to get in and out, he removed it. On another inspection round, he found the lock taped over again, and called the police, who eventually found five suspects. Wills quit his job soon after the burglary was discovered, believing that he did not get the raise he deserved. He later played himself in the 1976 movie version of “All the President’s Men.” Wills died in 2000 at the age of 52.

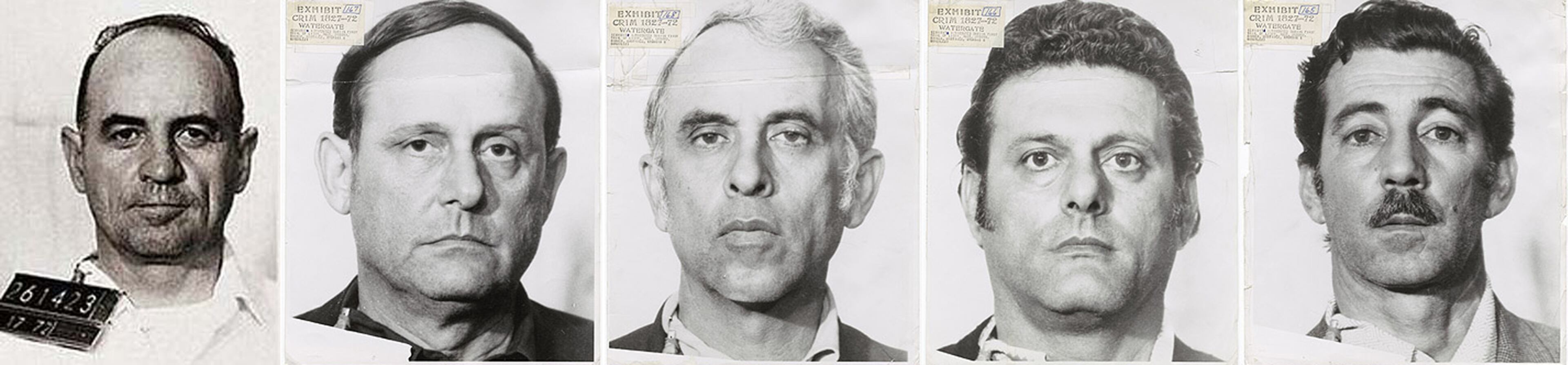

The suspects

McCord, chief of security for the Nixon reelection campaign and a leader of the “plumbers” unit, led the band of burglars. Later, McCord became the first to break the silence surrounding the break-in when he revealed at an arraignment that he had once worked for the CIA. He died in 2017 at the age of 93.

Bernard L. Barker, a Cuban-born American, was recruited for undercover operations during the Nixon administration by E. Howard Hunt Jr. The ties between the two went back to Hunt’s days in the CIA and the planning of the 1961 invasion of the Bay of Pigs in Cuba. He died in 2009 at the age of 92.

Eugenio Martínez, who was said to have infiltrated Cuba hundreds of times on CIA missions to plant anti-Castro agents there or extract vulnerable Cubans, was the only figure in the scandal besides Richard Nixon to be granted a presidential pardon. “I wanted to topple Castro, and unfortunately I toppled the president who was helping us, Richard Nixon,” Martínez said in a 2009 interview. He died earlier this year at the age of 98.

Frank A. Sturgis, a staunch anti-Communist, said Hunt had recruited him for the burglary by saying it was a mission essential to the nation’s security. He died in 1993 at the age of 63.

Virgilio R. Gonzales, a locksmith from Miami, was a refugee from Cuba who left following Fidel Castro’s takeover. He died in 2014 at the age of 88.

The first article

Although Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein became famous for their coverage of the scandal, the byline on the newspaper’s first article about the break-in, which appeared on the front page on Sunday, June 18, was that of veteran police reporter Alfred E. Lewis. Because of his contacts with police, he was the only reporter admitted to the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate on the day of the break-in. Years later, Woodward said Lewis was able to get the kind of details concerning the burglary and the burglars that convinced Post reporters and editors that this was no minor crime. “His work laid the foundation for what the paper was able to do in reporting the story,” Woodward said.

The aftermath

For months, White House aides tried to fend off reports suggesting ties between the president’s men and the burglars. But in January 1973, Hunt and the burglars pleaded guilty, and McCord and Liddy were convicted in a federal trial, all seven on charges of burglary, wiretapping and conspiracy. Disclosures by investigators and conspirators of a White House taping system that had recorded incriminating conversations between the president and his aides led to the brink of impeachment and Nixon’s resignation on Aug. 9, 1974. Dozens of conspirators went to prison, but Nixon was pardoned by his successor, President Gerald R. Ford, and died in 1994.

Sources: The New York Times, The Washington Post