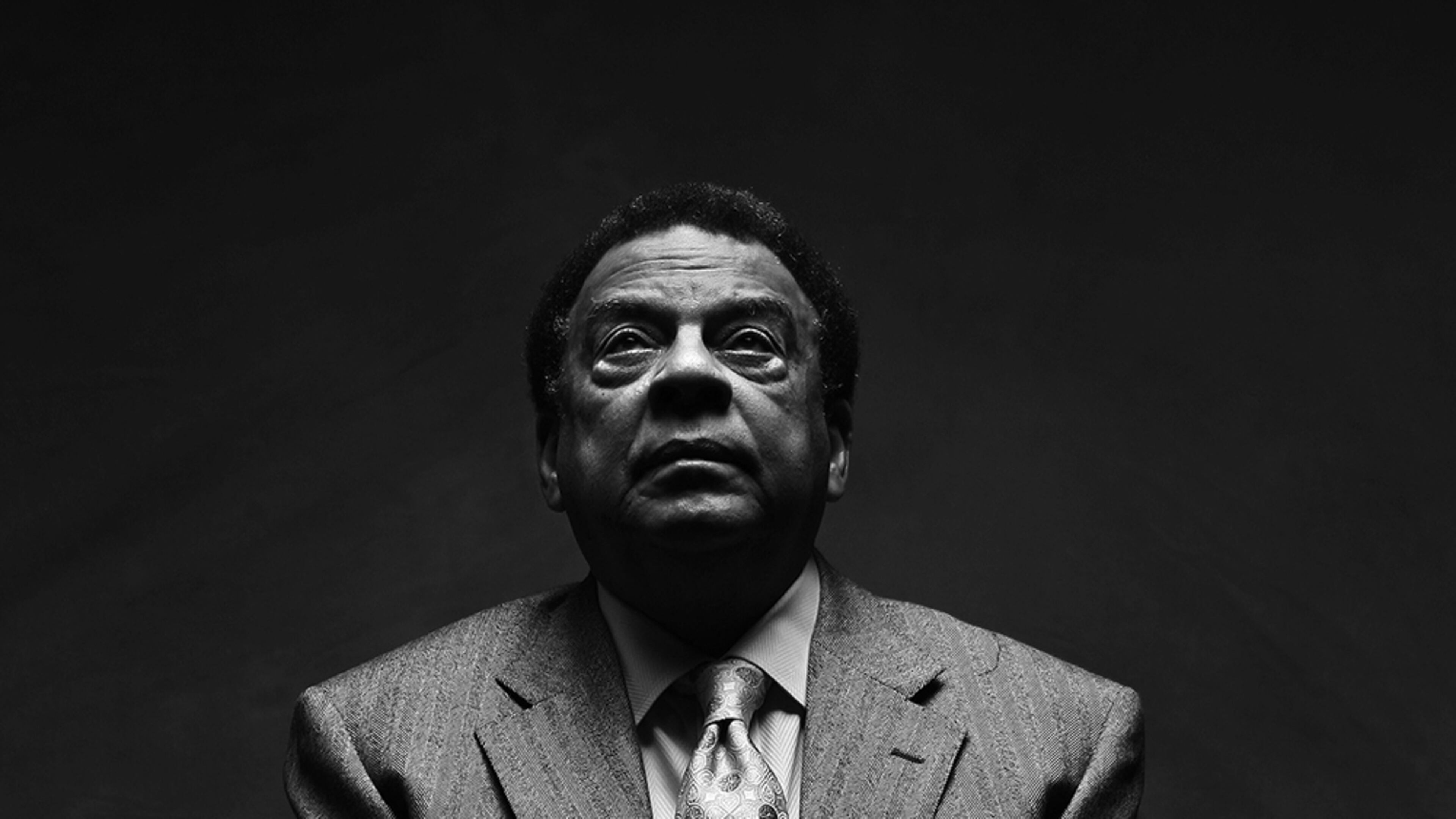

90 years of wisdom from Andrew Young

Andrew Young, who turns 90 years old this weekend, has a resumé Iike few others — pastor, civil rights hero, refugee resettler, congressman, mayor, United Nations ambassador, human rights champion, businessman and Olympic Games recruiter.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has followed his life since the 1960s. Below are a collection of some of his public comments over the years. Watch for the AJC’s coverage of Young’s birthday with exclusive interviews, photos, video and stories about him and his impact on this city and the world.

His childhood set his course: “My childhood was wonderful. It was segregated, but it wasn’t. I grew up in a (New Orleans) neighborhood that was completely diverse. There was an Irish grocery on one corner. An Italian bar on the other. The German-American Bund, heiling Hitler, was 50 yards from where I was born.

“By the time I was 2 or 3, my parents were having to explain white supremacy to me. There was no air conditioning; they would keep the windows open. I can see people ... heiling Hitler and singing “Deutschland Uber Alles.” My daddy did it by taking me to the Olympics movie to see Jesse Owens. He said white supremacy is a sickness. You don’t get angry at sick people, you help sick people. You prove to them that they are wrong. ... That shaped my childhood.”

In one of his books, Young says he told his grandmother about some white boys from outside his neighborhood calling him and his brother names. “Gran sat up straight in the bed. ‘If they call you (racial epithet), she said sternly, ‘you got to fight ‘em. If you don’t fight ‘em when they call you (racial epithet), I’m gonna whip you myself if I find out about it.’ "

His father imparted tough life lessons: “My daddy used to tell me all the time, don’t get mad, get smart. If you lose your temper in a fight, you lose. Even when I broke my arm and they had to set it with no anesthesia, he told me not to cry.

“I cry now, but I cry mostly for joy. I don’t cry when I am in trouble. I don’t cry in frustration. I cry over precious memories. It is almost like my cup runs over.”

Andrew Young at 90

The Atlanta Journal-Constituion is celebrating Andrew Young’s 90th birthday with these articles old and new:

Plans for Andy Young’s 90th birthday

Andrew Young looks back at 90 years and smiles, mostly

Timeline: Andy Young’s remarkable life

New book excerpt: The Many Lives of Andrew Young

Essay: Andrew Young: congressman, ambassaor, mayor, brother

Andy Young marches during 90th birthday celebration

Quotes: 90 years of wisdom from Andrew Young

Photos: Andrew Young through the years

On his early work in Europe, which many people know little about: “Jean and I, just before we married, went to Europe and worked in a work camp with refugees who were coming out of Eastern Europe. My work with the Council of Churches involved me with the churches from Africa, Asia, Latin America and Europe. That is where I began my international travels. I had been to Europe. I had been to Latin America. I had been to the Middle East. I hadn’t been to Africa yet, but I knew Africa well. One of the reasons I was able to do stuff with Martin (Luther King Jr.) was because I came into the movement with a different perspective, a more national and global perspective than, say, most of the people who came up just in the South.

On friends of his parents reacting to his early years as a civil rights worker: “All their friends were calling them from Montgomery and Tuskegee saying, ‘Why did you let your son get involved with those trifling preachers? They ain’t never gonna amount to anything.’

“.. Looking back on it now, what better opportunity in life than to be an assistant or flunky for Martin Luther King?”

He also recalled how he tried to manage tension in the movement’s leadership: “There were a lot of strong egos and a lot of people who wanted to be Martin Luther King, a lot of people who worked around him, in the other organizations and in ours, who resented him. My unique contribution was, not only did I not resent, I appreciated him. I did not want to be him. I simply wanted to help him. I didn’t care who got the credit.”

He likened his role to getting a sports team to play together: ”I played a little basketball with the strong egos around — James Bevel; C.T. Vivian, he did not have one of the strong egos but he was a very powerful man; Ralph (Abernathy); Joe Lowery; Hosea (Williams) — all of them were big shots. I saw my role as like a point guard. I made sure everybody got to touch the ball.

Young remembered being arrested in the city where he would later serve as mayor: “The first and only time that I was arrested in Atlanta, I was demonstrating for a salary increase for our sanitation workers. When the police came to arrest us, I said, ‘Excuse me, officer, may I say one thing before we’re arrested?’And he stopped. And I said, ‘Please remember we are on the same side. And, if the sanitation workers get a raise, you will too. And your children will get new shoes and clothing too.’ It brought a smile to his face as he snatched me up and put me in the wagon.”

He says he appreciates history: “... Because the more you understand it, the more you make sense of what’s going on now. History has been messy, just like it’s messy today. There are things we remember from the past that anchor us to deal with the future.”

He also says the most important part of his education didn’t come in a classroom: “I think the most valuable part of my education was in the nitty gritty dealing with poor people. If you put yourself in situations where you isolate yourself from poverty, you are not getting an education. What you study in books is irrelevant. What your test scores are are irrelevant. Your success factor is how you relate to people.”

Around the world, his importance is recognized: George Papandreou, the Greek minister heading his country’s efforts to land the Olympic Games over Atlanta in 1996, gave an assessment of Young. “He is widely respected. ... In Greece, he is not only a prominent but a well-liked person. And he is perhaps better known than his city, particularly in the Third World.”

What he would say to Martin Luther King Jr. if they meet again. “In one of the last meetings we had before his death, Dr. King said the future of America depends on whether we could get the energy, vitality and vision of the civil rights movement off the streets and into politics. If we do meet again in heaven, I might tell him that’s what I really tried to do.”

On the election of Barack Obama as president: “I often say that, marching from Selma to Montgomery, if I had said to Martin Luther King that I wanted to be a congressman, mayor of Atlanta, ambassador to the U.N., he would’ve thought I was crazy. I don’t think we were ever thinking of a Black president.”

On Democrats’ culpability in the election of Donald Trump: “We focus on human rights for gay marriage, for handicapped people, minorities, immigrants — and, all of that, I agree with. But the fundamental human right is a job. We forgot that in the Democratic Party. And that’s why we lost. It was not the Russians.”

Reflecting on his career and accomplishments on his 75th birthday: “Like I always say, life really begins at 40. And 40 to 50 is spring training. I was elected to Congress at 40. By the time I was 50, I was mayor. Then, I knew what I was doing, and I didn’t care who didn’t agree with me. ... So for the next 25 years, I have decided that I was gonna try to share the lessons we learned in Atlanta with the rest of the world. I also decided to work to strengthen the institutions in Atlanta that are responsible for Atlanta’s growth and development. I want to try to invest in the institutions that have invested in me.”