62 years later: Emory apologizes to medical school applicant rejected because he was Black

“I am sorry I must write you that we are not authorized to consider for admission a member of the Negro race. I regret that we cannot help you.”

That was nearly the whole response that a young Marion Hood got from Emory University on August 5, 1959, a week after applying to its medical school.

The last of the four sentences was a postscript from admission director L.L. Clegg: “I am returning herewith your $5.00 application fee.”

Hood gathered his $5 and went on to graduate studies before attending medical school at Loyola University in Chicago. Then he returned to Atlanta to establish himself as a respected gynecologist and obstetrician.

But that letter from Emory hangs in a frame in his home as a reminder.

More than six decades later, on Wednesday, as part of its Juneteenth programming, Emory’s School of Medicine apologized for it.

Emory University President Gregory L. Fenves acknowledged during the program that Hood was rejected for “no other reason that the fact that he was Black,” and that the letter, “vividly shows the systematic injustice of that time and the legacy that Emory is still reckoning with.”

“Throughout American history and Emory history, Dr. Hood and so many other talented students, were denied access to achieve their dreams to realize their potential,” Fenves said.

Hood, 83, said he never dwelled on the rejection, but at times Wednesday he got emotional when he talked about his experiences.

“The Emory deal in itself was good…to bring some closure,” Hood said. “Discrimination to me was an everyday part of life.”

Hood recalled an incident early in his career. He was treating a patient in an emergency room who spit in his face. About an hour later, the patient was perplexed that Hood was still taking care of him.

Fighting back tears as he recalled the story, Hood told the patient that as a doctor, he was obligated and wanted to take care of people, even ones he didn’t really like.

“You have to do it. I say to students, you can’t be disrespectful, and if you do that, everything will work its way out,” Hood said. He tied the story back to Emory. “Everything worked its way out. There was no reason to dwell on it. I did not expect to get into Emory.”

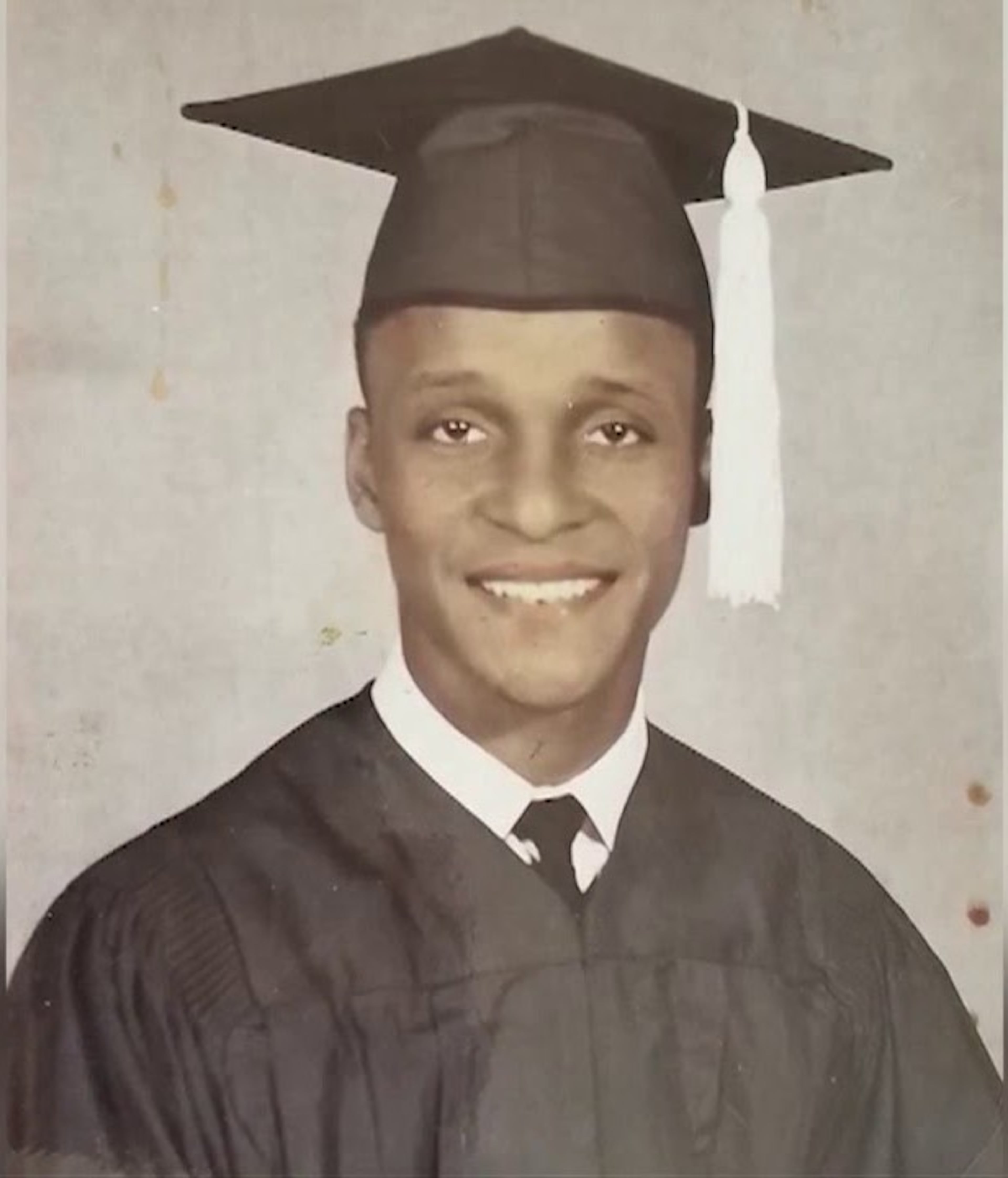

Hood, the son of a practical nurse, was enticed into applying to Emory after graduating from Clark College in 1959 with an eye on medical school. At his graduation, Hood was struck by the fact that Clark gave an Emory University professor an honorary degree.

“I thought, he can come to my school and get an honorary degree and I can’t put my foot on his campus,” Hood said.

He had already applied to Howard University and the Meharry School of Medicine, but immediately sent an application to Emory.

The rejection came less than a week later.

Hood had started a Master of Biochemistry at Howard when he was accepted to Loyola medical school in 1961.

Because he could not attend medical school in Georgia, the state paid part of his tuition.

He earned money on campus cleaning a white fraternity house. The house’s Black cook would save food for him every day.

“Life is full of hurdles, but if there is a hurdle, there must be a way to get around or over it,” Hood said.

Even though he was admitted to medical school, most of his professors never called on him, and when it was time to examine patients, he was always last. That is how he fell into obstetrics.

“The professor in OB-GYN asked me questions,” Hood said. “So I had to be extra prepared.”

Hood graduated in 1966, opened an Atlanta practice in 1974 and delivered more than 7,000 babies before he retired in 2008.

Emory desegregated three years after rejecting Hood, after it won its challenge of state laws which denied tax-exempt status to schools that racially integrated.

In 1963, the university admitted its first Black medical student, Hamilton E. Holmes, who in 1961, along with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, had integrated the University of Georgia.

Today, about 16% of Emory’s medical students are Black, said the school’s dean, Vikas P. Sukhatme.

Wednesday, Hood got another letter from Emory, this one from Sukhatme.

“On behalf of Emory University School of Medicine, I apologize for the letter you received in 1959 in which you were denied consideration for admission, due to your race,” Sukhatme said. “We are deeply sorry this happened and regret that it took Emory more than 60 year to offer you our sincere apologies.”