Police killings continue to rise two years after George Floyd’s death

A drunk boyfriend arguing loudly with his pregnant girlfriend outside an Airbnb home was a scary scene for Vine City resident Britt Jones-Chukura.

The man pushed the woman, but instead of dialing 911, Jones-Chukura, recalling the early 2021 incident across the street from her house, said she and neighbors talked to him and got him to simmer down.

“We did everything to calm that young man,” Jones-Chukura said. “I’m worried about what would have happened if we did call the police. This young man was in his feelings. But we had that fear of if you call the police, something worse could happen.”

Jones-Chukura, the co-founder of Justice for Georgia, a civil rights organization working to end police brutality which she founded four days after the death of George Floyd in 2020, said she’s learned that other Black residents in Atlanta neighborhoods are reluctant to call 911 due to fears the situation might escalate into a police shooting.

“I worry when my husband has to run errands,” Jones-Chukura said. “I say, ‘Just be careful. Make sure you are driving safe. Anything could happen.’”

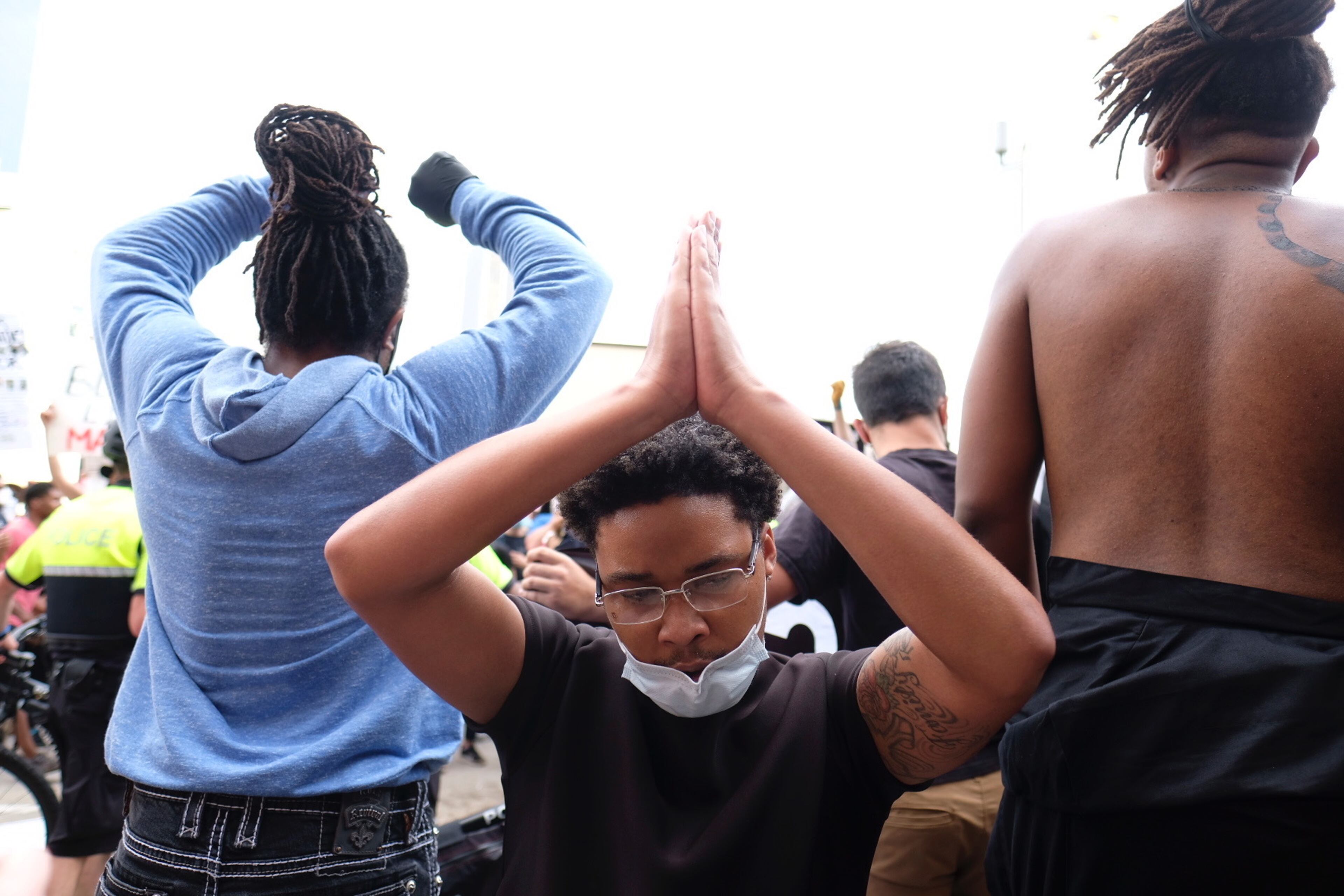

Fear of interactions with law enforcement is not a new phenomenon, but the killing of George Floyd by Minnesota police two years ago was a breaking point for communities across the U.S. long concerned with the inequitable treatment of Black Americans by law enforcement officers and the criminal justice system.

Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporters talked to metro Atlanta leaders about the substantial shifts that have taken place since Floyd’s killing, including increased scrutiny of law enforcement, new laws designed to make mental health care more accessible and the addition of behavioral health clinicians to assist police on calls.

While it is difficult to gauge whether any criminal justice reforms will improve the public’s trust, it’s clear that police budgets are bigger than ever and more people — civilians and law enforcement officers — are dying during violent confrontations.

Floyd’s death on May 25, 2020, while pinned to the ground by then-officer Derek Chauvin, spurred a national outcry for cities to address policing and race. Protesters took to the streets, forcing confrontations. Many cops — including more than 200 in Atlanta — retired or resigned while under increased legal and media scrutiny.

The public’s trust in police took a hit, according to data from Pew Research Center. A December 2021 survey said 31%, almost a third of all respondents, had little to no trust in police.

Minorities have the least faith in police, according to the non-partisan think tank. Only 10% of Blacks in late 2020 said they had a great deal or fair amount of trust in police, followed by 16% of Asians, 18% of Hispanics and 32% of white people.

Kim Parker, Pew’s director of social and economic trends, said that among white respondents, younger adults expressed less confidence in police than middle-aged and older adults.

Police accountability

Georgia NAACP President Gerald Griggs said the organization hasn’t seen significant adjustments in transparency and accountability by police departments.

“Trust (in the police) has not increased,” Griggs said. “There’s still a concern about the number of police involved shootings. There’s a lot of talk of changes and being accountable. I have yet to see that turn into anything actionable.”

Griggs said NAACP leaders talk with Georgia residents weekly and meets with FBI and GBI officials monthly to address concerns and questions about investigations into police shootings.

Griggs criticized the Fulton County District Attorney’s Office, which he says has numerous open cases in the court system involving police shootings dating back to 2016.

“There are 97 open cases that I know of in the Fulton D.A.’s office with no resolution,” Griggs said.

Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in April that her team has resolved nearly 50 police use-of-force cases, choosing to indict in some instances and declining to bring charges in others. Willis did not speak to the AJC for this article, nor did her office provide details of how the use-of-force cases were resolved.

Last week, DA spokesman Jeff DiSantis said the office is moving through the years of such cases inherited from Willis’ predecessor, Paul Howard. DiSantis did not confirm the number of open cases that remain but said the DA’s office is working on incidents that occurred in 2019. He pointed to recent indictments of police officers as signs of progress.

In April, a Fulton County grand jury indicted two East Point officers on charges including aggravated assault in the shooting of Devin Nolley who, in 2018, fled police questioning and was shot in the back twice following a chase on I-285.

Two officers were indicted on felony murder charges last fall in the killing of Jamarion Robinson, who was shot 59 times in his girlfriend’s apartment in East Point by members of a federal task force. A trial date has been set for September.

U.S. Marshals were trying to serve arrest warrants on Robinson when he was killed in August 2016. One was for allegedly pointing a gun at officers in a previous encounter. Another was for attempted arson. Weeks earlier, Robinson poured gas on the floor outside his mother’s bedroom and was seen trying to set it on fire, according to court records.

“If you ask me if I trust or have faith in police, absolutely not,” said Robinson’s mother, Monteria Robinson, adding her son was diagnosed with schizophrenia in 2015. “... The trust (in police) is broken in the African American community.”

Robinson points to the death of Nygil Cullins, 22, who was shot and killed by Atlanta Police last week at Fogo de Chao Brazilian Steakhouse in Buckhead, as evidence police methods have not improved when dealing with those experiencing mental issues.

Police were called to the restaurant by staff concerned about an unruly patron. Officers fired after Collins shot a security guard, Atlanta police said.

Cullins’ mother told the AJC she called 911 hours before he died seeking help in transporting him to a mental health facility. He was at home, his family said, but he became anxious and had left by the time police and paramedics arrived nearly two hours later.

Bigger police budgets, more homicides

Since Floyd’s killing, violent crime and metro Atlanta police budgets have exploded.

Atlanta ranked No. 3 among large U.S. cities for the highest increase in the homicide rate during the pandemic. APD investigated 160 homicides in 2021, up from 99 in 2019. This year, at least 59 Atlanta homicides had been investigated by late April, up from 40 at the same time in 2021.

It wasn’t just Atlanta; gun violence exploded across Georgia, the AJC reported.

Police spending is up too. Since 2019, the budgets of metro Atlanta’s four largest police departments has grown by more than $100 million, an average of 20%.

Metro Atlanta police departments facing a shortage of officers have raised pay to attract new (and former) recruits. Smyrna cops got 28% raises as the city struggled to fill vacancies. Fulton County Sheriff Patrick Labat offered new hires 20% of their annual salary as a bonus — a $9,000 bonus for a $45,000 position, plus $3,000 in moving expenses if coming from out of state. In Brookhaven, where the base pay for a cop with no experience is $48,500, new hires are eligible for a $10,000 bonus.

In DeKalb County, the proposed budget includes $14.1 million to improve retention, recruitment and training for police, fire, and other public safety personnel. Current DeKalb officers will receive a $3,000 retention bonus, new hires were eligible for a $5,000 hiring bonus.

Statewide figures for police salary increases are difficult to come by. No state agency or organization tracks what police are paid, according to officials with the Georgia Peace Officer Standards and Training Council and the Georgia Association of Chiefs of Police.

GACP will start collecting that information next year, said Butch Ayers, the association’s executive director who served as Gwinnett County police chief until his retirement in 2019.

Ayers said police salaries increased most in metro Atlanta.

“It’s a hypercompetitive market,” Ayers said. “It’s the law of supply and demand. Fewer people want to be police officers and that has driven up labor costs.”

Police working today face higher risks, Ayers said.

“Assaults, felonious assaults against officers has increased in recent years. There is a chance of going to work and being killed or sued and losing everything. Officers weigh their options” and some choose another profession, he added.

Seventy-three U.S. law enforcement officers were killed in 2021, more than any year since the Sept. 11 attacks in 2001, according to FBI data. Forty-four of the 73 were killed in the South. In 2020, 46 officers were killed, including 24 from Southern states.

From 2012 to 2021, Georgia was ranked third in felonious killings of police officers with 27 behind only Texas (59) and California (40).

The number of certified police officers in Georgia is dropping. In January, the state had 29,686 certified officers, down by more than 2,000, or 6.8%, from the same month in 2020, according to POST data.

Why the decline?

“It’s a combination of things,” said Terry McCormick, POST’s Certification and Training Division director. “COVID played a little piece of it, some of the negative social media posts turned officers away from it and some found better paying private-sector jobs.”

Many police departments are working with fewer officers than they want. Ayers said 254 law enforcement agencies responding to a 2021 survey indicated they were 17% below full strength, with 16,138 positions filled. Fifty-nine agencies reported they were at 100% strength; 83% of those had 25 or fewer officers.

New police tactics

The increased police funding is being used on new measures such as the hiring of behavioral health clinicians to assist police on calls.

In Gwinnett County, mental health professionals have been going on police calls since July 2021. Officials there say the program provides residents with resources they can use to get help and it can reduce violent incidents with police.

Before clinicians were added, those experiencing a mental health crisis would have to call the Georgia Crisis Access Line, which could sometimes take hours to get a response. Now, residents are able to have a mental health professional and an officer on the scene within minutes, Gwinnett County police Lt. Jordan Griffin said.

The new team has been out on hundreds of calls, Griffin said, including a Greyhound bus incident on I-85 in March. Gwinnett officers and SWAT team members felt the suspect, Jaylin Backman, 23, was having a mental health crisis when he pulled out a gun while arguing with a fellow passenger.

Officers decided to call clinicians from the behavioral health unit to assist. Backman, after hours of negotiations, was taken into custody unharmed and given a mental health evaluation. He’s currently out on bond on one count of aggravated assault, according to jail records.

Pej Mahdavi, director of the intensive outpatient services program for View Point Health, the service that partners with Gwinnett, said clinicians can help police get the best outcome.

“If somebody is going to go fix something ... they’re going to ... need a screwdriver, and a wrench and a hammer and all that kind of stuff,” Mahdavi said. “I think with the police it’s the same thing. You know, you see a situation ... there’s several tools that I may need in this, it may be SWAT, it may be canine, it may be behavioral health unit, it may be anything else. So you go and you get all those tools so you’re ready.”

In Johns Creek, mental health experts have assisted police on more than 200 cases, Police Chief Mark Mitchell said. Clinicians can first engage the person in need when police are called to the scene, or at a later date. A clinician has accompanied officers on about 50 emergency calls, according to the city.

The death of Floyd sparked controversy in the north Fulton city when the former police chief made disparaging comments on social media about the Black Lives Matter Movement in June 2020. Former Police Chief Chris Byers resigned following an investigation into an unrelated issue but his social media comments contributed to the city’s decision to form a citizen panel to help to select Mitchell as the new police chief last year.

The International Association of the Chiefs of Police conducted the search and surveyed residents to determine what qualifications they wanted to see in the new chief. Mitchell and other finalists met with the panel of residents before the final selection was made.

Mitchell said the police department is building relationships with diverse community groups across the city and the agency is building a Community Ambassador Team with representatives from Black, Jewish, Indian, Muslim, Korean, and Indian-Hindu communities. The team’s purpose will include open discussion on policing concerns, what best practices are in law enforcement and more, he said.

In Cobb County, Flynn Broady, a reform-minded district attorney elected after Floyd’s death, created a new policy that allows for the dismissal of criminal charges if participants complete a diversionary program. Cobb County has four accountability courts overseen by Superior Court judges: drug treatment, mental health, veterans and parental accountability. Broady said the programs help participants become productive members of society and has reduced the recidivism rate of participants by 70%.

Less successful in Cobb County was the Council for Justice, Peace and Reconciliation, which was meant to be a citizens advisory board to identify racism and promote social and economic equity. Approved by commissioners in 2020, it never convened, county spokesman Ross Cavitt said. Instead, the county plans to hire a diversity, equity and inclusion director to address such issues.

New mental health laws

Georgia ranks 48th in the U.S. for access to mental health care, resources, and insurance, according to the Mental Health Association of Georgia.

Brookhaven Police Chief Gary Yandura said laws passed this year will make it easier for Georgians to get help.

The Mental Health Parity Act (HB 1013) requires insurance companies in Georgia to cover mental health just as they cover physical health, making treatment more accessible.

The Georgia Behavioral Health and Peace Officer Co-Responder Act (SB 403) makes it possible for police to check those suspected of experiencing mental health issues into a treatment facility without making an arrest. Previously, officers had to get a doctor or certified clinician to sign off on whether a person qualified for a mental health evaluation.

“The jails are too full,” said Yandura, who serves on the board of the Georgia Chapter of the National Alliance of Mental Illness. “Most of the time, people need help more than incarceration.”

Since 2005, state law enforcement agencies have pushed Crisis Intervention Training for officers, which teaches de-escalation techniques and other methods for reducing the arrests of people with mental illness. Yandura said 70% of Brookhaven officers are CIT certified, but the goal is 100%.

Fatal police shootings increase

Any accounting of police violence is incomplete. No state or federal laws require police departments to report when people are injured or killed by police. The FBI’s National Use-of-Force Data Collection program, started in 2019, has released no data on police violence due to the lack of volunteered information.

Georgia police agencies lag the nation in submitting information to the FBI. In 2021, 66 out of 775 Georgia agencies provided use-of-force data, representing 36% of sworn law enforcement officers in the state, the FBI says. Nationally, about 54% of officers were covered by agencies that submitted data last year.

The most complete accounting of fatal police shootings in the U.S. is maintained by a newspaper, not government. The Washington Post reported that in 2021 police shot and killed at least 1,055 people, up from 999 in 2019. Black people are killed at twice the rate of white people, the Post reports.

Former Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, acting on recommendations by an advisory council after the 2020 protests, had a use-of-force dashboard created “to improve transparency, increase trust between the public and APD.” In 2021, APD had been involved in three fatal shootings by August, but the dashboard indicates an APD officer had used a gun only once.

A spokesperson for Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens said the dashboard would be updated: “Thank you for bringing this to our attention. The Q4 data is being processed for upload as we speak, with Q1 of this year to shortly follow. It appears as though a staffing reassignment caused a delay in the transmission of data from APD to (the Atlanta Information Management department). This has been addressed and we anticipate more timely quarterly updates going forward.”

By law, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation must be asked — typically by a city or county police chief — to participate in any investigation, including police shootings. The agency began publicly posting lists of officer-involved shootings it investigates in 2020.

The AJC requested information dating back to 2017. While the number of police shootings per year in Georgia has remained fairly constant, fatalities more than doubled from 2017 to 2021.

In 2017, the GBI said it investigated 97 police shootings and 27 fatalities. In 2021, there were 100 police shootings with 57 people killed. The pace has increased in 2022, with 52 shootings and 25 fatalities recorded by May 23.

Derek Chauvin was convicted in April 2021 of second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter in Floyd’s death.

Monteria Robinson said she sees progress with such programs as Atlanta’s Police Alternatives & Diversion Initiative which now, in addition to its other services, works to reduce the arrest and incarceration of people facing extreme poverty or mental health issues.

But law enforcement still has a long way to go to stop excessive use-of-force, she said, adding that Jamarion’s case will be referenced for years when discussing excessive force by police in Georgia. The 59 bullets that hit him caused 76 wounds, a memory that still haunts her, she said.

“I do have anxiety bad and trouble sleeping each day, but who wouldn’t after their child or loved one was killed in the manner in which Jamarion was killed,” she said. “Police are not the judge, jury and executioner ... Police officers’ jobs are to apprehend, not go into situations with guns blazing ... Empathy goes a long way ... If you aren’t trained to do something, call someone who is well-equipped.”

-- Atlanta Journal-Constitution journalists Wilborn P. Nobles III, Jennifer Peebles, Mandi Albright and George Mathis contributed to this article.