Promised changes to Confederate imagery at Stone Mountain slow coming

The Confederate flags are still there. All four of them.

They still fly a few hundred paces up Stone Mountain, high atop their poles in a stone plaza, where the hundreds or thousands of people who summit the granite outcropping each day can’t help but plod past.

Some 15 months ago, the state authority that manages Stone Mountain vowed that the flags would be moved to a less visited part of the park: a relatively simple undertaking as the Stone Mountain Memorial Association made baby steps toward offering a “21st-century perspective” at the home of the world’s largest Confederate monument.

Documents obtained through the Open Records Act show a contract for the relocation work was actually signed almost a year ago.

But the flags are still there.

“We just kind of put it on the back burner and left it there,” memorial association CEO Bill Stephens admitted in a recent interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Stone Mountain’s longtime private management partner pulled out at the end of July, citing “protests and division” among its reasons. Stephens said the transition to a new manager for the park’s attractions, hotels and conference centers has “taken the oxygen out of the room for anything else.”

The memorial association has a small staff, he said. Its board of directors meets once a month, if that.

Board chair Rev. Abraham Mosley echoed Stephens statements.

“I don’t think we are moving fast enough” on promised changed like the flag relocation, he said. “But because of the transition and those things that took place, we can’t move any faster.”

The Stone Mountain Action Coalition, a grassroots organization that has pushed for a sweeping reformation at the park, said that’s not a good excuse.

In an emailed statement, the group said that recent years have seen U.S. military bases named for Confederate leaders rebranded. Confederate monuments in local communities and across the country have come down.

But Stone Mountain leaders, the activists said, have “yet to rename a single Ku Klux Klan or Confederate street or feature [or] remove Confederate flags from hiking trails, and actually permitted a large Confederate event that they knew was being promoted by neo-Nazis and white nationalists.

“The public deserves to know why there has been no progress at Stone Mountain Park,” the statement says.

‘Months, not years’

Stone Mountain was the birthplace of the second Ku Klux Klan. The creation of the enormous carving of Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee that graces the mountain’s northern face spanned decades, and the effort has ties to both the Jim Crow era and government resistance to desegregation.

A century after the end of the Civil War, the park was created to serve, by state law, as a monument to the Confederacy.

Protests there are nothing new.

Such efforts, though, found new energy during 2020′s nationwide protests over police killings of Black Americans and institutional racism. The Stone Mountain Action Coalition coalesced that year and joined forces with local NAACP branches and other longtime activist groups to put pressure on Stone Mountain leaders.

By November 2020, a memorial association official was vowing that a new, more inclusive perspective would come to the park. The work, he said, would take “months, not years.” The decision was based in no small part on economic struggles at the park.

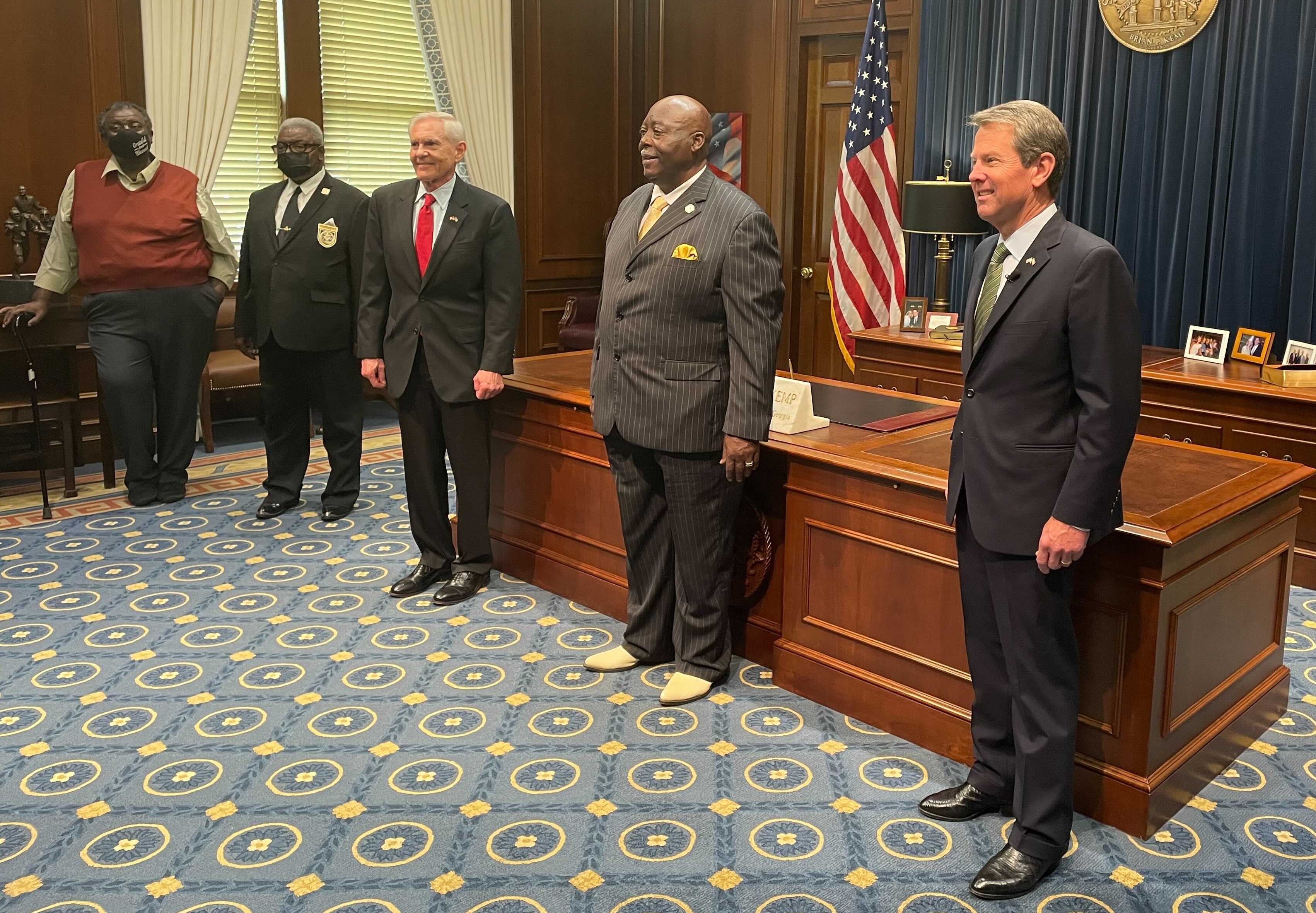

Gov. Brian Kemp appointed Mosley as the SMMA board’s first-ever Black chairman in April 2021. A few weeks later, the board approved a series of changes.

Relocating the walk-up trail’s flags to an existing pocket of Confederate tributes at the foot of the park’s main lawn was among the approved moves. So was the creation of a new museum exhibit that Stephens, the SMMA CEO, said would “tell the truth” about the ugly history of the park and its carving.

Progress has been made on that end, albeit slowly.

The memorial association issued a request for proposals for companies interested in building the exhibit last October. The submission period ended in April.

Stephens said the board could name a winner later this month.

“They’re major companies” that submitted bids, Stephens said, “and we feel like they can tell a complete and whole story.”

Once a company is selected, work on the exhibit — which will be housed at the park’s existing Memorial Hall — is likely to take many, many months. If not years.

A stalled ‘start’

To be clear, the approved-but-still-to-come changes at Stone Mountain Park don’t fully satisfy anyone.

Groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans, of course, want nothing changed. They’ve even suggested leaning further into the park’s ties to the Civil War South.

Activists from groups like SMAC and the Atlanta NAACP want the memorial association to go much further. The park is filled with streets named for Confederate leaders, including the men on the mountain, Admiral Raphael Semmes and John B. Gordon, a former governor and senator who is generally acknowledged to have been the leader of the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia.

A lake at the park is named for Samuel Venable, who owned and operated Stone Mountain as a granite quarry when the idea of a Confederate carving was first dreamed up in the 1910s — and who helped bring the Klan back to life.

“The [currently proposed] changes still maintain a monument to white supremacy,” said Atlanta NAACP president Richard Rose, who has protested the park since at least 2015. “So nothing they can do short of removing those carvings and changing those names would make a difference.”

Mosley has previously expressed support for some name changes, and said he expects the idea to “resurface” as a point of discussion.

But they’re not currently on the table.

Some activists, meanwhile, saw the relocation of the Confederate flag plaza as a partial win. Memorial association leaders have maintained that state law prevents the flags from being removed altogether, but at least folks trying to walk the mountain for entertainment or exercise wouldn’t have to see them if they didn’t want to.

Stephens said the memorial association remains “committed to doing what the board has already approved.” But he didn’t know when the existing flag plaza contract with local engineering firm Pond & Co. would be picked back up.

“That would have at least been a start,” Rose said. “Not a great start. But a start.”

STORY SO FAR

In May 2021, the state authority that controls Stone Mountain Park agreed to make a handful of changes to Confederate imagery at the popular attraction. They included moving Confederate flags from the base of the mountain’s walk-up trail and creating a “truth-telling” exhibit at the park’s on-site museum.

Some 15 months later, a vendor for the museum exhibit could be chosen soon. But the flags remain where they’ve flown since the 1960s.

-

Nov. 2020

Stone Mountain Memorial Association chair Ray Smith says a "21st-century perspective" will come to the park in "months, not years"

-

April 2021

Gov. Kemp appoints Rev. Abraham Mosley at the first Black chair of the memorial association board

-

May 2021

The relocation of Confederate flags on the mountain's walk-up trail and the creation of a 'truth-telling' exhibit are approved

-

Aug. 2021

The memorial association removes the Confederate carving from its logo

-

Sept. 2021

The memorial association contracts with an engineering firm for the Confederate flag relocation; the flags, though, remain in place

-

Oct. 2021

The memorial association issues an RFP for the 'truth-telling' museum exhibit at Memorial Hall

-

May 2022

Thrive Attractions is chosen as the new private management company for the park's revenue-generating attractions

-

Aug. 2022

Thrive formally takes over for longtime management partner Herschend Family Entertainment

-

Sept. 2022

The memorial association could select a company to create the 'truth-telling' exhibit; the walk-up trail flags remain in place