40 years ago, higher education’s face altered

This story was originally published on Jan. 7, 2001, marking the 40th anniversary of the integration of the University of Georgia.

Though the University of Georgia was supported in part by the taxes of the state's black population, in 1960 it had no African-American students, teachers or athletes on its campus.

But on Jan. 6, 1961, U.S. District Judge William Bootle ordered the university to admit Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter, making them the first two African-American students ever to attend the school and changing the face of higher education in Georgia.

Both outstanding graduates of Atlanta's all-black Turner High School, Holmes and Hunter came to UGA as transfer students from Morehouse College and Wayne State, respectively, where they went after being denied admission to UGA as freshmen. They had first applied to the all-white institution in 1959, encouraged by the Atlanta Committee for Cooperative Action, a group of black professionals that had previously been involved in a failed attempt to desegregate the Georgia State college of business administration.

When news of Bootle's order reached Athens, 200 angry white UGA students staged a protest that night at the Arch, the historic entrance to North Campus, where they hanged an effigy of Holmes, sang "Dixie" and chanted epithets. Later that night, campus officials prevented them from burning a cross in front of UGA President O.C. Aderhold's house on Prince Avenue.

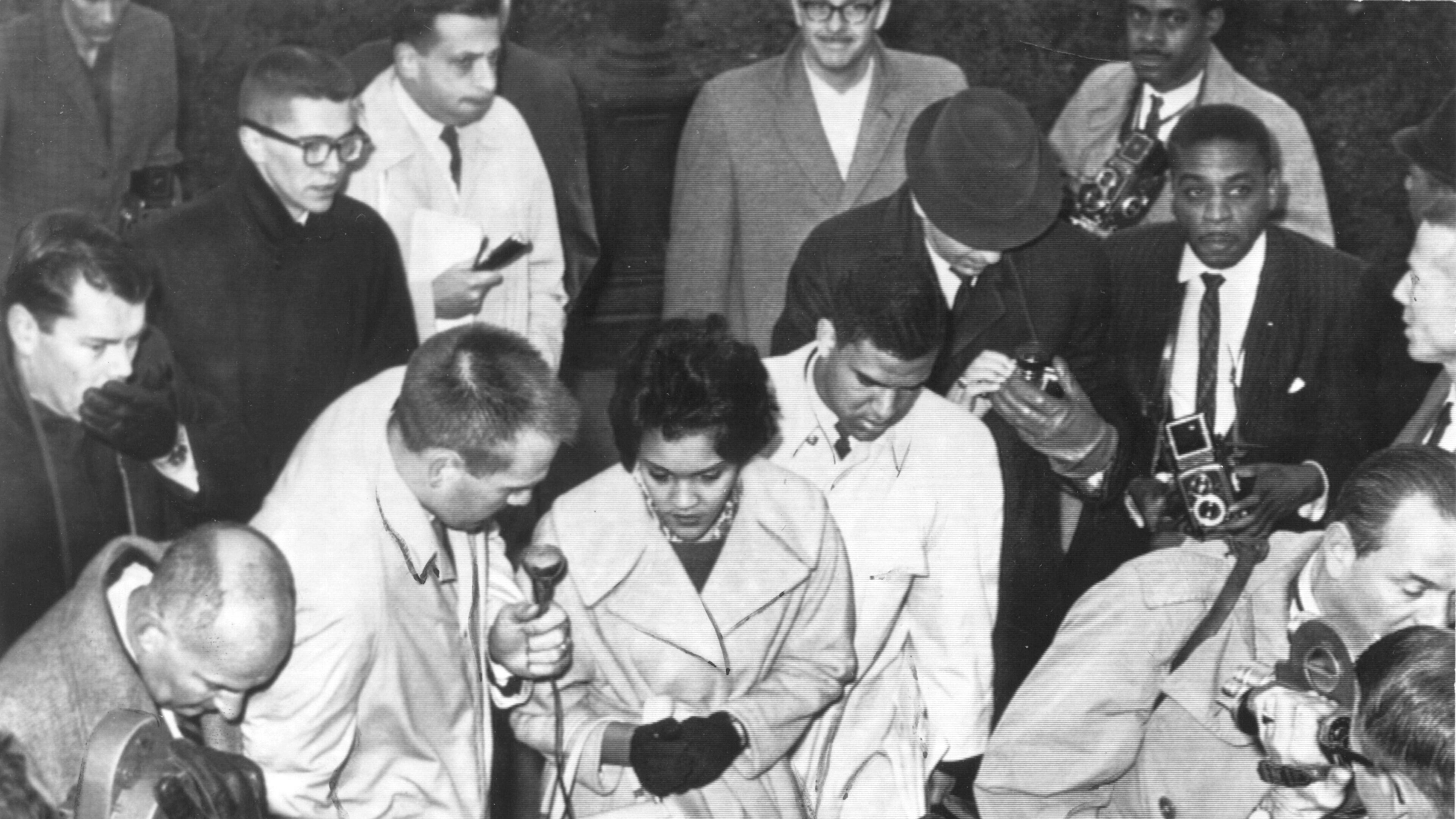

On Jan. 9 -- 40 years ago Tuesday -- Holmes and Hunter registered for classes, joining the 7,000 or so other undergraduates in Athens as the first black students since the university’s founding in 1785.

In her memoirs, "In My Place, " Hunter, now Hunter-Gault, recalls going to sleep that first night in Myers Hall, a women's dormitory, while people outside chanted.

The two students attended their first classes that Wednesday, with Holmes taking science courses needed for medical school and Hunter heading into journalism. As she recounts in her memoirs, her second class of the day was journalism ethics, taught by Dean John Drewry.

Then-student Joan Zitzelman remembers being about to take her seat in the class when she noticed a racial epithet scrawled across the blackboard. Zitzelman says she couldn't imagine the dean, or Hunter, reading such hateful words.

While 50 or so other students watched, Zitzelman stepped to the blackboard and erased the message, “wondering at the time if any of my classmates would have the audacity to write it again, and if I’d be able to erase it. Luckily, the Dean and Charlayne came in shortly afterward and class began.”

Though Hunter-Gault writes that she felt upbeat about the reception she had received in class and at her dorm, the evening of Jan. 11 revealed an ugly side of UGA. Rumors had circulated throughout Athens that a riot would occur Wednesday night -- both students and residents knew it.

Like many others in town, Archibald Killian, whose family was housing Holmes, received word that the Klan was coming to Athens that night, “and I sent word back, that if they came, we’d kill them,” he said. “They figured if they could scare us, Hamp wouldn’t have a place to stay, and they’d be back to zero. But we didn’t scare easy, and they didn’t come.”

After a basketball game between UGA and Georgia Tech --- which Tech won in overtime ---protesters gathered across Lumpkin Street from Hunter's dorm under a banner bearing a racial slur. One account estimated the crowd at 2,000.

For more than two hours, they shouted and cursed, hurled bricks and bottles at dorm windows, set fires in the adjacent woods, scuffled with police and threw rocks and firecrackers at reporters, according to newspaper reports.

"It was a giant, unruly mob, the first I'd ever seen, " said Athens resident Pete McCommons, who, as a UGA student, was watching in the Myers quandrangle like many others. "It was terrifying."

In her memoirs, Hunter notes she later learned that the other Myers residents had turned off their lights, as the riot planners requested, making her well-lit room an easy target. Though Hunter wasn't injured, another young woman was hit by a brick while she looked out her window.

It took the Athens police more than an hour to break up the crowd, using tear gas and fire hoses. Numerous people, including six Klansmen, were arrested. Holmes and Hunter were suspended from UGA "for their own protection, " Hunter was told, and were taken from Athens by the Georgia State Patrol, which arrived around midnight to transport them to Atlanta.

Though journalists and Athens residents had asked Gov. Ernest Vandiver to send in the State Patrol, which had offices in Athens, the governor didn't, and no State Patrol officers came during the riot, according to UGA historian Robert Pratt, who is writing a book on UGA's desegregation.

The next day, UGA math professor Thomas Brahana spotted six armed Klansmen across Lumpkin Street from Myers Hall. He said he contacted the FBI, who arrested the men on charges of carrying concealed weapons when they deposited their rifles in a car trunk.

"There's some mythology that the riot was spontaneous, but it was common knowledge that it was going to happen, " said Pratt. He believes those who organized the riot hoped to force the two black students from UGA "permanently, the way that Autherine Lucy --- the first black student at the University of Alabama --- had been forced to leave."

Pratt's extensive research has shown that an FBI investigation revealed "conspiracy and collusion" between state legislators and the UGA students who planned the event. Lt. Gov. Peter Zack Geer publicly praised the students after the riot "for demonstrating and fulfilling their constitutional right of protest."

During the riot, "students were overheard boasting that lawmakers were supporting them and had promised them immunity, " Pratt said. "It was a conspiracy." None of those arrested was charged with breaking any laws.

What those leading the riot didn't count on, said Pratt, was the reaction of the UGA faculty. The morning after the riot, Brahana, who was president of the campus chapter of the American Association of University Professors, called for a meeting of the faculty, which took place in the Chapel that evening, Jan. 12. There was fear among faculty that Aderhold or the governor might move to close the university.

"We knew the university would be integrated, even if the federal government had to send in the Army to do it, " said Brahana. "And if they did send in outside forces, the effect would have been terrible. Individual opinions became a secondary thing to the potential damage to the university."

Of some 600 faculty members, 406 signed a resolution thanking Aderhold and administrators for carrying out the law, condemning the riot and those involved in it, calling for the immediate reinstatement of Holmes and Hunter and asking "that all measures necessary to the protection of students and faculty and to the preservation of orderly education be taken by appropriate state authorities."

"The riot offended us, said retired English professor George Marshall. "It galvanized people who had been on the sidelines and got them active."

At the same time, about 1,000 Athens residents signed a petition voicing their confidence in Aderhold, Dean of Men William Tate, Athens Police Chief E.E. Hardy and Mayor Ralph Snow.

The next few days saw attempts by some members of the state General Assembly to censure Aderhold and an effort by segregationist Roy Harris, a member of the state Board of Regents, to fire the UGA president and all the faculty members who signed the petition --- all of which failed. Harris had accused the president and others at the university of attempting to "conduct an experiment in race mixing."

The day after the riot, Judge Bootle overturned a Georgia law, passed in the 1950s, that would withdraw state funds from any higher education institution with black students. The next day, on Jan. 14, he ordered UGA to reinstate Hunter and Holmes by Monday morning.

After the two returned, the Legislature passed a resolution encouraging the university to readmit those 20 or so students who had been suspended for participating in the riot. Over the protests of many on campus, the offending students were allowed to come back.

For a while after they returned to Athens, Hunter and Holmes were escorted to classes by federal agents, but gradually, the security measures relaxed, the crowds thinned and the national media interest seemed to wane. A little more than two years after they entered UGA, Hunter and Holmes graduated. Elected to Phi Beta Kappa at Georgia, Holmes became the first black student to graduate from Emory University Medical School, eventually becoming an orthopedic surgeon. He eventually forgave UGA and even came to love the school, becoming the first African-American to serve on the UGA Board of Trustees. He helped establish the Holmes-Hunter Scholarship for black students. When his son, Chip, chose to attend UGA in 1986, Holmes said he was pleased, because "UGA is a great school and he'll get a good education." Holmes died in 1995 at age 54.

The dream that Charlayne Hunter-Gault had cherished since childhood of working in journalism came true. She worked for the New Yorker, the New York Times and PBS, and is currently the South Africa bureau chief for CNN. In 1988, she was the first African-American to deliver the undergraduate commencement address at the University of Georgia.

“We had our victory, " Hunter-Gault said. “It wasn’t about the institution --- there were many decent people there, and those who weren’t have moved on. But it’s important to keep alive the memory.”