Why there’s now a sixth stage of grief: Finding meaning

For a year after he helped write the landmark “On Grief and Grieving,” David Kessler contemplated the role meaning plays when grieving the loss of a loved one. If finding meaning is important in our lives, he asked himself, was it also important when coping with the loss of a loved one?

More importantly, did it demand adding a sixth stage to the five stages of grief that had already been put forward by his late co-author Elisabeth Kübler-Ross — denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance?

In 2014, Kessler began writing on meaning but soon put it aside to do a lecture tour of Australia.

A few years later, while lecturing on the East Coast, he got a call that his younger son David had died of a drug overdose.

“I canceled all my lectures, and a couple of months later in my office in enormous pain, I ran across those chapters I’d written on meaning,” he said. “I started reading. It didn’t take the pain away, but it gave me a cushion.”

In that moment, Kessler knew he was on to something.

He realized, he said, a couple of things.

RELATED | 2 strangers come together to find the good in suffering

First, the stages he and Kübler-Ross introduced had been misused and misinterpreted over the years.

“People began to think of those stages as five neat steps, and that was never our intention because you can go through all the stages in one day,” he said. “They are not linear. They have been very organic and so I wanted a chance to clear up some of those misperceptions, especially around the stage of acceptance.”

For the record, acceptance took on a finality that neither of them ever intended. It didn’t mean being OK with the loss or that the grief was over. Simply put, it meant having acknowledged the reality.

Second, he wanted people to know that after acceptance, there’s meaning. Sometimes that means starting a charity or foundation. Other times, it can be finding meaningful moments.

“When we think about them, people will sometimes say are you asking us to find meaning in their death?” Kessler said. “No, but to look at whether there was meaning in their lives, have you been changed because of them? People will often say, ‘A part of me died with my loved one.’ That’s true but a part of your loved one lives in you. And that part is meaning.”

Ultimately, Kessler decided that not only did he need to add a stage to the grieving process, there was a book to write.

“Finding Meaning,” now in bookstores across the country, details stories of losses of parents, siblings, spouses and other family, including the death of his son and how it led to him, with permission from the Kübler-Ross Family Foundation, adding the sixth stage of grief, where he believes hope and healing can be found. Kessler also explores the science behind grief and how our minds “can be Velcro for the bad memories and Teflon for the good ones,” and offers tips for remembering those who have died and moving forward in a way that honors their loved ones.

“Meaning comes through finding a way to sustain your love for the person after their death while you’re moving forward with your life,” he said. “That doesn’t mean you’ll stop missing the one you loved, but it does mean that you can experience a heightened awareness of how precious life is.”

RELATED | Can you really die of a broken heart?

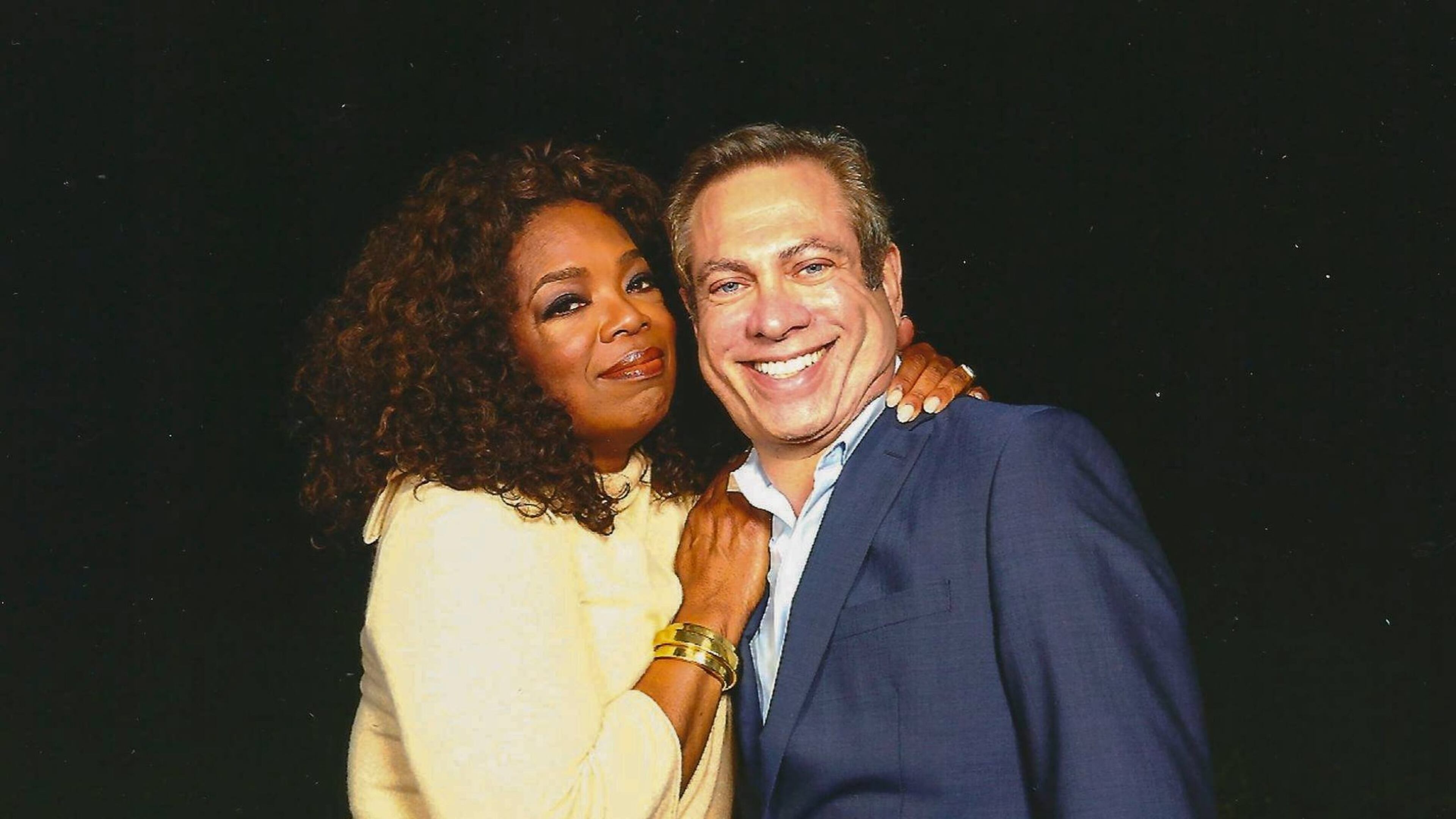

During a break from a book tour through Georgia late last month, Kessler shared some of the details of his journey with me.

With the holidays fast approaching, I asked him about the grief that often revisits us because we find ourselves for the first time with an empty chair at Christmas dinner or some other holiday meal when a loved one’s absence rings so loud.

“It is especially hard because the message of the holidays is togetherness and you’re not with the ones you want to be with,” Kessler said. “We forget someone is gone this year who was here last year.”

So we try to avoid thinking about them, try to push away the sadness and put on a happy face or worse, friends and family tell us to move on and get over it.

Truth is grief isn’t something to get over because we don’t. We simply learn to live with it.

The question is how?

Kessler suggested finding a way to incorporate your loss into the holiday. That could mean lighting a candle in their honor, mentioning them in the prayer, making their favorite dish, or inviting everyone to tell a favorite story of their life.

Kessler remembered interviewing a woman whose father was a diabetic who loved sneaking M&M’s. After he died, they always had a bowl of the candies out in his honor.

While we grieve the dead who loved us, Kessler said we also grieve people who were simply absent from our lives for one reason or another, or who were there but might have treated us poorly.

“We have to remember that grief isn’t just about death and dying,” he said. “We grieve for the people who just aren’t in our lives, the spouse who left us, the father who’s not there, the relatives who aren’t talking to each other anymore. All those are real losses, too.”

Interestingly, Kessler told me that the questions he gets asked the most are “is there life after death for my loved one and do I believe in an afterlife.”

“My answer is yes,” he said. “I believe in an afterlife and then I tell them, I have another question for them. Is there life after death for the living, do we get to live again? I meet so many people whose life has been shut down and I want to help people grieve fully but also live fully and live a life that honors their loved one who has died.”

Kessler’s son had considered pursuing a career in medicine or in some helping profession. In kindergarten, he was voted the most likely to grow up to become a helper.

“Today he’s helping a lot of people,” Kessler said finally. “This book has given his life meaning.”