Every Day Is Sunday: As atheism rises, nonbelievers find one another

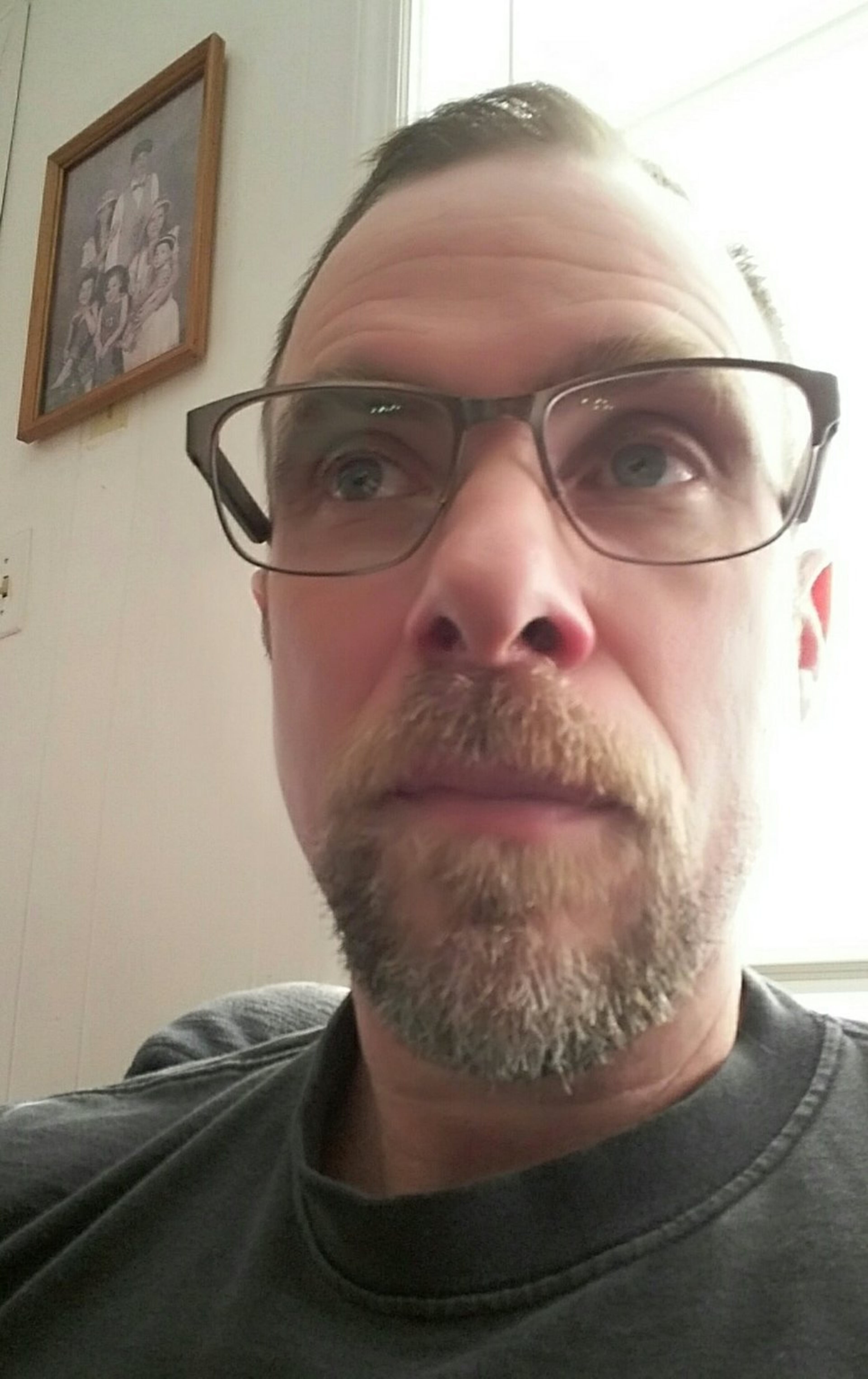

Jeff Newport can cite the Bible chapter and verse.

He went to Christian schools, attended church every Sunday and delivered his first sermon at 13.

In 1996, he was called to pastor a small Baptist church in Jesup with a congregation of about 30 for Sunday morning services.

“Everything revolved around church,” Newport said. “We would not have even thought of missing a service unless we were ill. Family Bible reading and prayer were normal activities — we never had a meal, even in public, for which we didn’t say a blessing.”

Today, though, the 46-year-old Savannah man considers himself a nonbeliever.

He lost faith in faith.

It’s not easy being a nonbeliever or a skeptic in the Bible Belt South.

Move to a new city. Start a new job. Or meet a potential romantic interest.

One of the first things you’re asked is: Where do you go to church?

RELATED: 7 churches, 1 building: A Clarkston church that offers a reflection of Atlanta’s religious diversity

RELATED: Liberal or conservative? Religious outlook can blur the answer

RELATED: Faith in Atlanta photo essay

Religion is big in these parts. It can be the social center of a person’s life. Often friendships are built within the walls of a sanctuary. Families worship together. Faith and where you worship not only give people a sense of believing but belonging.

Still, atheism (or at least the acknowledgment of it) appears to be on the rise — though slightly.

Pew’s 2014 Religious Landscape Study found that 3.1 percent of American adults say they are atheists, up from 1.6 percent in a similarly large survey in 2007. An additional 4 percent of Americans call themselves agnostics, up from 2.4 percent in 2007.

The Washington, D.C.-based Secular Coalition for America, for instance, boasts 29,000 people on its mailing list and more than 130,000 followers on its various social media accounts. Its followers include atheists, agnostics, humanists and other nonbelievers or those who aren't sure of the presence of a higher spirit.

That’s an increase in 2016 of more than 5,000 new subscribers on their email list, more than 7,000 new Twitter followers and more than 10,000 Facebook likes.

Turning away

For Newport, it was a gradual change. For most of his early life, he never doubted the existence of God or the doctrines of Christianity.

The more he attempted to learn and weigh evidence pro and con, the more that faith began to unravel.

He left the Baptist ministry in 1999 and converted to the Eastern Orthodox Church. During his 12 years in this tradition, he gradually laid aside some of the dogmas of Christianity — the reality of a literal hell, the inerrancy of the Bible, the exclusivity of Christianity as the only way to God, among others.

At the same time, he developed a love of science and the reliability of an evidence-based approach to find truth.

In 2012, he took a job that required work on Sundays. It gave him time and space to re-evaluate his faith. “My faith couldn’t stand up to this scrutiny. By the middle of 2014, I had quietly, but firmly, decided I no longer believed in God or the supernatural.”

He has never approached the topic with his parents, who are dyed-in-the-wool Christians.

“I think they would be disappointed, and would certainly worry about my soul if they knew I no longer believed,” Newport said.

Newport is a member of the Clergy Project, which was formed in 2011 to create a safe and secure online community for former and current religious leaders who no longer believed in God. Many of the former pastors and church leaders prefer to remain anonymous, in part because of fear of being ostracized by family and friends. For pastors, stepping away from the pulpit can also mean loss of income.

The organization has more than 750 members in 34 countries.

Initially, all were from Christian backgrounds, but its members now include Muslims and Buddhists.

About a third of its members still serve in religious leadership positions, although they no longer believe in a higher power. “It runs the gamut from more scientific stuff to more theological questions,” said Drew Bekius, president of the Clergy Project. “They see tragedy in the world, yet you see people claiming God just got them a parking space. So God will answer the prayer for a parking space while millions of people are in poverty?”

For others, it’s more personal. Perhaps there was a personal heartbreak or death of a loved one. Perhaps they saw immense suffering and wondered how could God allow people to suffer?

"A large part of it is that people are dissatisfied with the moral teachings of some of the religions they belong to," said Casey Brescia, a spokesman for Secular Coalition for America. "For instance, a lot of people are turned off by their church's position on LGBTQ equality. But also people are beginning to find community elsewhere. Churches don't play the same role in the community they used to. It's just a wide variety of factors."

He sees a growing number of younger Americans who eschew any religions, and that, he said, is a “tectonic shift. That means that people are walking away from church and walking away from institutions that used to play such an important role.”

In what has become an annual holiday tradition, American Atheists launches billboards nationwide urging viewers to celebrate an "atheist Christmas" by skipping church. Several of the locations in Southern states will be up later this year to promote the solar eclipse convention the atheists will host in Charleston, S.C., in August 2017.

“It is important for people to know religion has nothing to do with being a good person, and that being open and honest about what you believe — and don’t believe — is the best gift you can give” during the holiday season, David Silverman, president of American Atheists, said in a release about the holiday billboard campaign.

Doubts and discomfort

It’s hard to say how many atheists there are in the United States. Even the Pew Research Center has trouble giving an exact number. Why?

According to a survey by the Atheist Alliance International, most people who identify as atheists, agnostics, humanists, freethinkers, nonreligious or secularists are male, college-educated and more than a third are between the ages of 25 and 34.

Mandisa Thomas, the founder and president of the Black Nonbelievers, a 3,000-member organization based in Atlanta, grew up in a black nationalist household.

“In this age of information,” she said, “a lot of traditional notions are not holding up anymore. We are beginning to see the world is not right. We’re told to just have faith or pray on it. That’s just not enough for people anymore.”

It’s especially hard for African-Americans, she said.

“Religion is still so ingrained in the black identity that to openly state that one is atheist means that you’re rejecting your race and culture.”

Nonbelievers often talk about how uncomfortable it can be to navigate a world that can be largely faith-based.

“You get a lot of unnecessary attention, and most of it is negative,” said Deric McNealy, 28, a machine operator who lives in Jonesboro. “People always try to come up and save you. They try to speak to you about God all the time or badger you, and that makes work very uncomfortable.”

McNealy grew up in a Christian family that included church leaders.

He began to question things in the Bible at an early age.

As McNealy became older, he “began to apply critical thought to all aspects of my life, and religion just happened to be one of the main things.”

His family wasn’t too happy.

“I think it’s a lot easier today than in the past because of the internet,” he said. “In the past, there was no community, no communications for people who questioned their beliefs. Now we go online and link with like-minded individuals.”

Atlantan Ross Llewallyn, who identifies as atheist, grew up in a Methodist household in Atlanta. “I had a good time going to Sunday school and the service,” said the 28-year-old software engineer. Over time, he began to think more about the presence of God.

“I was always someone of science and reason and tried to be true and accurate in my understanding of the world,” he said.

Take prayer, for instance. He was always told that before going to bed, he should get on his knees by the side of his bed and pray. He prayed for good things to happen to family, friends and himself. Soon he questioned whether he really needed to be on his knees. Why not just in bed? And why did he have to say his prayers aloud? Couldn’t God just hear his thoughts? “I started thinking more critically about things like that,” he said.

EVERY DAY IS SUNDAY

Sunday may be the prominent day of worship in Atlanta, but that's changing as a growing number of other religions establish congregations in our global city. This is an occasional series that examines how religion impacts life in Atlanta. You can read the earlier entries in the series on myajc.com.