This Life with Gracie: Let’s consider how labels can hurt

In a small fifth-floor office downtown, a 19-year-old talks about how being labeled a criminal just because he is black makes him feel and it isn’t good.

“It’s dehumanizing,” he said.

Some people will read that and automatically think this is just one more attempt to victimize African-Americans. Quavontaye Scott hopes you’ll resist the urge to make snap judgments, and listen to him. Listen to Foluke Nunn. Listen to every black and brown kid who has ever had to traverse the world with a label attached to them.

At-risk. Delinquent. Underprivileged. Underserved.

We create labels to make sense out of complex pieces of data. Labels can be particularly useful to qualify people for services and programs. And they can make us feel empowered to take action.

RELATED: Liberal or conservative? Religious outlook can blur the answer

But labels, the words we use to describe what we see, aren’t just pointless placeholders. They shape our perception of people, color what we see.

That fact has weighed heavily on Nunn and Scott for quite some time now because it isn’t something they just heard. As African-Americans, they experience it every day.

Nunn is a 24-year-old youth organizer in Atlanta with the American Friends Service Committee. AFSC was founded by Quakers during World War I to give young conscientious objectors ways to serve without joining the military. They drove ambulances, ministered to the wounded, and stayed on in Europe after the armistice to rebuild war-ravaged communities.

The organization, based in Philadelphia, would soon turn its focus to social justice, supporting among other things, the civil rights movement and the desegregation of public schools.

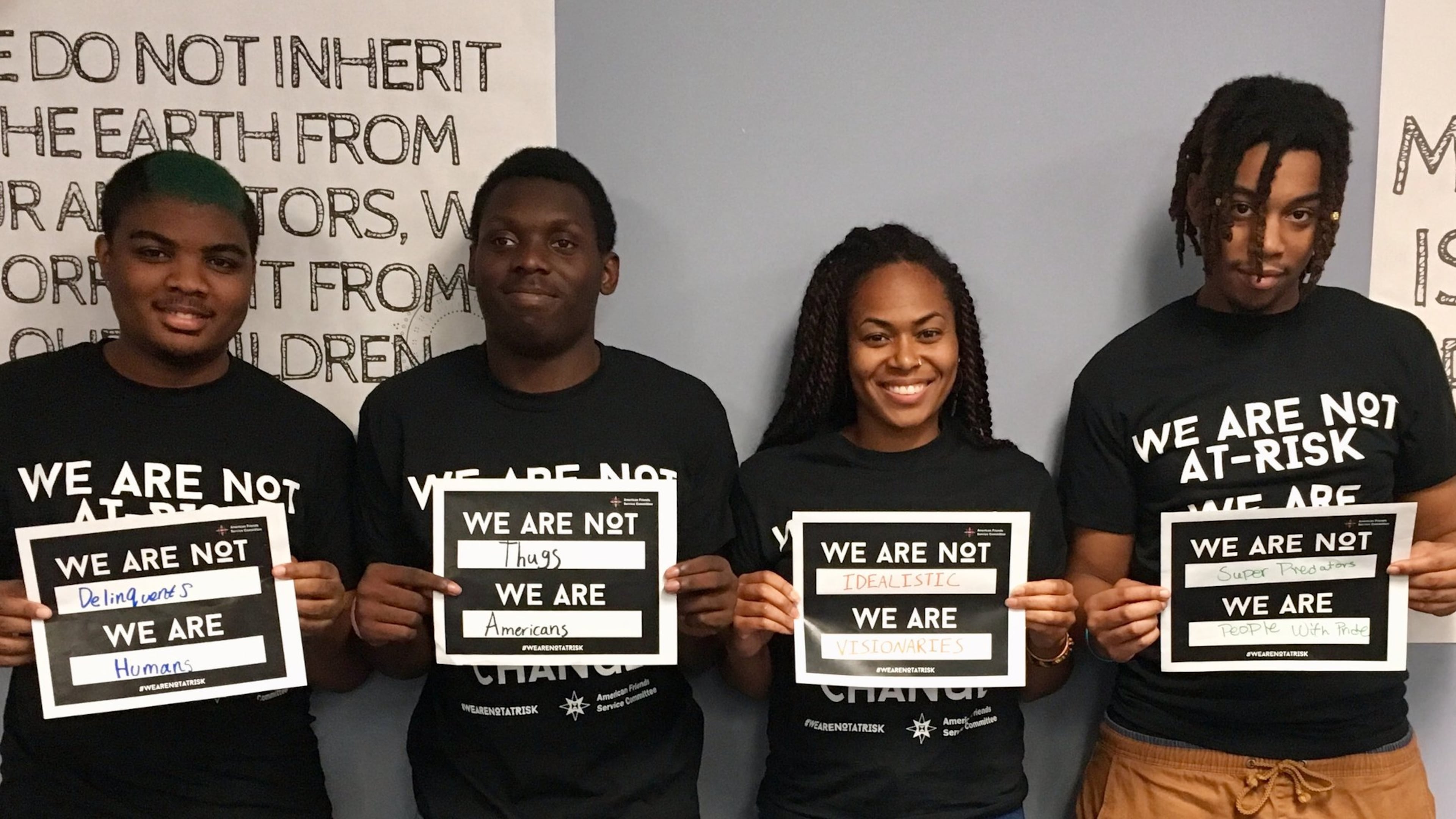

Nunn and Scott are both a part of the Atlanta Youth Organizing Project — a new AFSC initiative that helps youths ages 17-25 build organizing skills and become changemakers in their communities.

Last year, AFSC youth leaders from across the globe — the U.S., Kenya, Guatemala, Somalia, Indonesia — gathered in Nairobi, Kenya, for its second Youth in Action summit to discuss how systems of oppression impact their respective communities, and how they can work together to strengthen them. The conversation soon turned to how youths are spoken about and how that impacts how they see themselves and how they are able to move through the world.

By the time the summit ended a week later, they’d vowed to continue those conversations and launch a campaign to raise awareness about the power of words and end the use of “coded, racist and colonialist” language often used to describe black and brown young people.

RELATED: Are black girls worse than white girls?

This effort came to be called "We Are Not At-Risk", a 14-day social media campaign that culminated Nov. 14 with an international day of action and a pledge to not use harmful language to describe minority youths.

“So often when people talk about young black people who come from low-income communities, their words come from a perspective of lack: thug, delinquent, words that paint young people as criminal,” Nunn said. “They describe them as at-risk, underserved or vulnerable. Both sets of words highlight people’s deficits and can turn into a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Even when those labels come from well-meaning places likes nonprofits, she said, they can be harmful.

“It’s important to realize that when words like at-risk become the dominant narrative in someone’s life, it’s hard to not internalize them and so it strips you of your potential,” she said. “These words also put the focus on the individual, and take responsibility away from the larger systems and factors that can impact a young person’s decisions and experiences. Labeling makes it easy to turn a blind eye to the influence of racism or poverty.”

Labeling kids makes it difficult to show them empathy because it makes it harder to realize they are much more than their actions. Labeling makes it harder to correct behavior. It makes kids feel terrible about themselves.

Quavontaye Scott said that when he hears people refer to African-American males like him as thugs and criminals, it makes him feel “like an animal thirsting for a kill.”

“I want to be seen just as a regular person,” he said. “I’m actually pretty smart and it would never occur to me to do anything criminal. It pains me to think people see that when they look at me.”

Listen to him.

Find Gracie on Facebook (www.facebook.com/graciestaplesajc/) and Twitter (@GStaples_AJC) or email her at gstaples@ajc.com.