Here’s why diseases caused by insects are becoming more prevalent

Diseases caused by insects are booming.

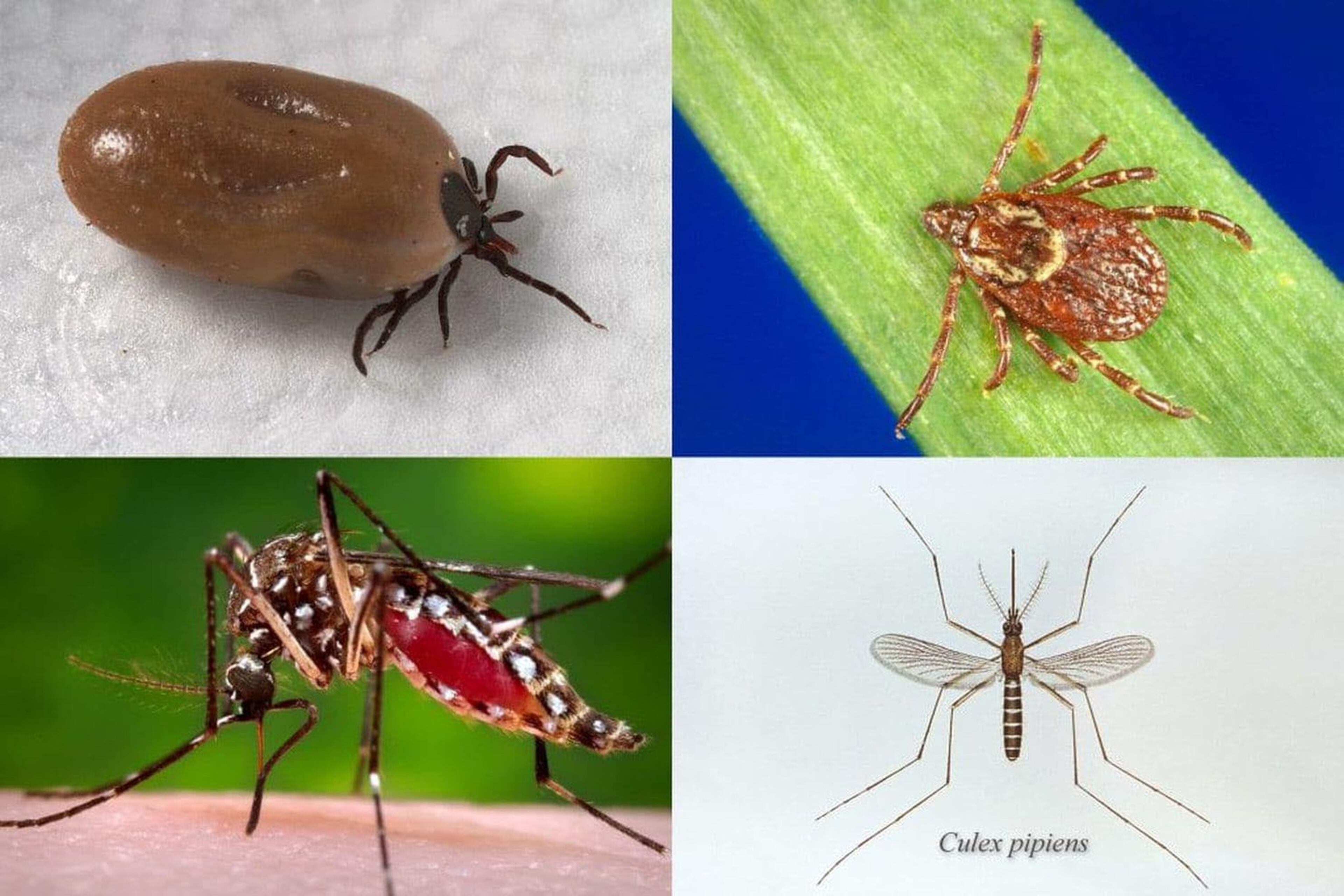

Earlier this month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that illness spread by ticks, mosquitoes and fleas had tripled since 2004.

Between 2004 and 2016, there were more than 640,000 reported cases of insect-borne diseases, according to the agency, and the numbers are growing.

So why are insects making us sick more often?

In an interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Dr. Lyle Petersen, director of the CDC's Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, explained the separate trends that are combining to promote the spread of these illnesses.

The first of these trends is the expansion of global trade and global travel.

In the 1950s, said Petersen, each year about 50 million people crossed an international border. Today more than a billion people cross an international border every year.

Crossing with them are new diseases that are then propagated in new territories. "We've increased international travel by 20 times, so it's no surprise that we're seeing this onslaught of imported mosquito-borne diseases," said Petersen. Among the new mosquito-borne diseases that have entered the U.S. are West Nile, which arrived in 1999, chikungunya (from 2014) and Zika (from 2015).

One of the most significant of these is still the West Nile virus. Each year, between 700 and 3,000 Americans who contract the virus develop severe neurological symptoms. "Most of those people do not recover fully, and about 10 percent will die," said Petersen.

“It doesn’t make the news so much — people have gotten used to it,” he said, “but it’s still a very deadly disease and the fact is, you could die from one mosquito bite. So it’s still important to take precautions.”

Far more widespread than the neurological disease is a milder version called West Nile fever, which affects 30 to 50 times as many people as its neurological cousin. These victims do not suffer paralysis or meningitis or encephalitis, but they will develop a body-wracking fever that lasts for weeks.

“While it won’t kill you, it will definitely ruin your summer,” said Petersen, “and I know that from personal experience.”

Petersen lives in Fort Collins, Colo., and he was one of the first people in that town infected by the disease. “It took me about three months to fully recover,” he said. The experience, during the summer of 2003, was unpleasant in the extreme. “It was the last time I ever called West Nile fever a mild disease.”

Another trend is pushing up the incidence of tick-borne disease. Deer ticks are moving into new territory due in part to warming temperatures, an expansion that is steadily raising the incidence of Lyme disease.

Petersen said up to 350,000 a year contract Lyme disease. “It doesn’t kill many people, but if left untreated, they can develop heart problems, they can develop neurological problems, they can develop severe arthritis.”

Another trend is making the matter worse: Fewer predators and bigger suburban forests have led to a boom in the deer population. "There are more deer, and more deer ticks, and the diseases they spread."

Could we solve this problem by eliminating the deer, or by reducing their numbers drastically? Deer lovers might not approve. “A lot of people like the deer,” said Petersen, “so it’s a very controversial subject.”

In Georgia, there are also tick-borne diseases that many haven’t heard of, but can wreak havoc. One of these is ehrlichiosis, which can lead to fever and multi-organ failure. Caused by the bite of a lone star tick, the disease can progress rapidly. “Within a matter of days, it can go from mild to severe illness and even death,” said Petersen. “Left untreated, it gets severe very fast.”

Dealing with these diseases is complex. There are 1,900 separate "vector control" organizations, including public health departments, mosquito-control districts and other local agencies.

Coordinating the efforts of all these groups is difficult, said Petersen. Control organizations need to do better surveillance of mosquito and tick populations and collect better data on the effectiveness of insecticides. Backyard fogging companies may have success in preventing nuisance mosquitoes, but there's no data on whether they are actually reducing disease, he said. They also may be aggravating our problems by producing more mosquitoes that are resistant to insecticide.

In the meantime, said Petersen, we can all help prevent disease by using insect repellent, wearing long sleeves and long pants, using clothes and gear (like backpacks and tents) impregnated with permethrin, and keeping ticks off our household pets.

And, taking a page from Brad Paisley, Petersen also recommends checking for ticks as soon as you come inside. To develop Lyme disease, for example, requires a few days' contact with a tick. If you get it off quickly, it won't have time to infect you, said Petersen.