Warming waters, disease threaten Georgia shrimp

Wassaw Sound Estuary, GA.—The fall of 2013 should have been a blessing for Georgia shrimpers.

A bacterial infection had wiped out the Asian shrimp farms that drove many Americans out of business. Early sampling at the time indicated a bumper crop of white shrimp on the way. Many poured money into fixing up their boats in preparation for long, rewarding days on the water.

But the nets came up empty.

“They were gone,” recalled Dr. Marc Frischer, a microbiologist at the University of Georgia’s Skidaway Institute of Oceanography near Savannah. “There were no shrimp.”

Wildlife officials and shrimpers clashed over the cause of the sudden die-off. What followed was years of research by a team of scientists across the South. The results of those efforts show how changes in the climate are likely impacting Georgia’s coastal ecosystems, and those who depend on them to make a living.

“I’m 100 percent a believer,” said Richard Puterbaugh, president of the Georgia Shrimp Association. “I had a front row seat for 45 years. I’ve seen the change.”

Shrimping has, historically, been vital to the food, culture and economy of the Georgia coast. Today, it makes up a tiny fraction of state’s gross domestic product. Still, this shrinking industry supports hundreds of jobs and brings in millions of dollars.

As shrimpers follow their crop north into colder waters, and a new shrimp parasite reaches epidemic proportions, scientists are investigating how changes in climate could influence the future of shrimp and shrimping in the Southeast.

“Temperature, current, rainflow — all of those are related to climate and all of those play very critical roles in the complicated biology and ecology of the system,” said Frischer. “Not just for shrimp, for everything.”

After the shrimp disappeared in 2013, the government declared a fishery disaster. Officials cited extreme rainfall that likely prevented shrimp larvae, hatched offshore in the ocean, from returning to the estuaries where they grow to maturity.

But shrimpers were unconvinced. They blamed black gill, a mysterious affliction that was becoming increasingly prevalent in shrimp harvested off the Georgia coast. Named for the immune response that darkens the crustacean’s gills, black gill is harmless to humans who eat the shrimp and does not affect taste. But it weakens the animal, making it more vulnerable to predators and less likely to survive.

A reporter for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution recently joined Frischer and his colleagues aboard the Research Vessel Savannah to study black gill in the Wassaw Sound Estuary. The intention of the annual stakeholder cruise is to bring together shrimpers, academics and wildlife officials to share research and observations.

Black gill remains a source of tension — particularly between shrimpers, who say it is devastating their crop, and wildlife managers, who say they have no evidence of that.

Mike Younce of Brunswick was a commercial shrimper for two decades. He said he first started noticing black gill, and its effect on shrimp, in the late nineties.

“The shrimp that didn’t have the black gill, they would be lively,” Younce said. “They would be jumping when they hit the deck.”

The shrimp with darkened gills, however, were small and sickly, their shells soft.

“They were outta gumption,” said Younce. “Like they were wore out.”

Solving the mystery of black gill

Scientists knew black gill was caused by an immune response in the shrimp’s body, but to what? Where did it come from, and why was it spreading?

Frustration over the failed 2013 harvest pushed the Georgia Sea Grant, part of a federal program based at colleges and universities, to prioritize funding for black gill research.

Since then, scientists have established that the black gill seen in Georgia shrimp is caused by a ciliate — a single-celled organism that attaches itself to the animal’s gills. Ciliates are fairly common hitchhikers on shrimp, but they had never been known to cause problems.

“There aren’t actually that many experts in the world that work on ciliate parasites of crustaceans,” Frischer said. “We showed [our research] to all of them, around the world, and nobody had seen anything like that before.”

It took years of collecting, dissecting and studying shrimp, but, in 2019, scientists were finally able to put a name to the scourge: A brand new species of ciliate they called Hyalophysa lynni after a well-known marine biologist, Denis Lynn, who died in 2018.

Much work remains to be done in order to determine how, exactly, the parasite feeds and spreads. In the meantime, it has reached epidemic proportions off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina, and appears to be moving into the Gulf of Mexico and as far north as the Chesapeake Bay.

Dr. Stephen Landers, the protozoologist at Troy University in Alabama who identified Hyalophysa lynni, said the species "broke the mold" of how this type of ciliate was expected to behave.

“Parasite species don’t just evolve in 50 years,” Landers said. “This is something that’s been on the planet for millions of years. Now, at this time, in this part of the world, for whatever reason, it’s thriving.”

Experts say there appears to be a strong correlation between black gill and climate conditions. While correlation does not equal causation, this theory is supported by experiments in the lab on the shrimp themselves.

In one study, changing water temperature by just two degrees had a huge impact on mortality rates for shrimp exposed to the parasite—a difference of up to 70 percent.

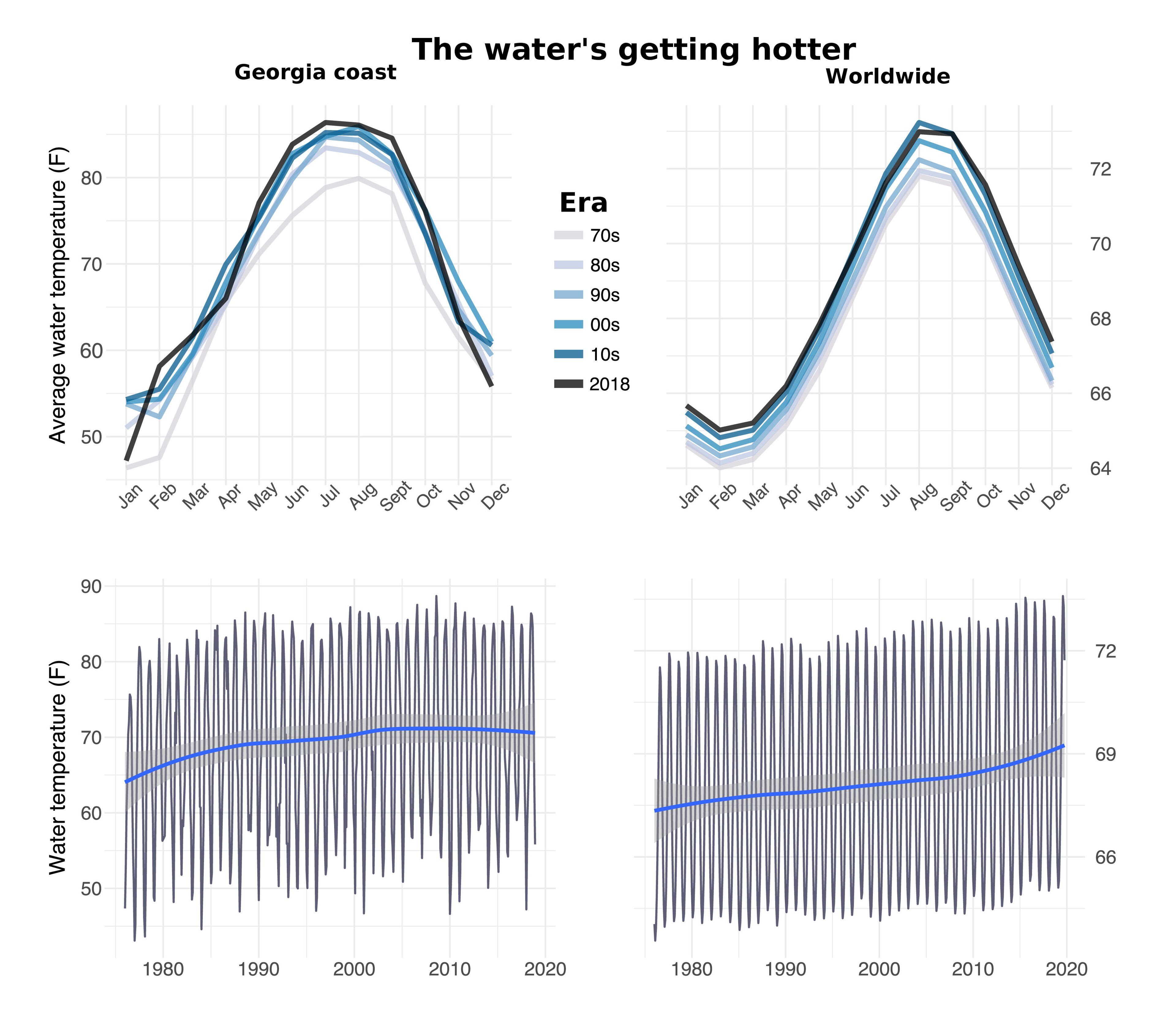

Coastal water temperatures in Georgia have increased by nearly five degrees over the past four decades, according to data collected by the state. Even with seasonal variation, the increasing trend is clear. Using a commonly employed statistical test developed by U.S. government scientists, the AJC concluded that such a consistent and steady increase is unlikely to arise randomly.

“Most infectious disease in aquatic animals is worse with rising temperatures,” said Eddie Leonard, a marine biologist with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. “I don’t think it’s unlikely that there is some relationship between global temperature and infection rates, including for black gill.”

Warming waters, warming planet

In order to understand what’s happening to Georgia’s coast, it’s important to understand why global temperatures are — on average — rising.

Earth’s atmosphere is so thin, compared to the planet’s size, that it has been compared to the parchment skin of an onion. Most of the ultra-thin layer that supports life is made up of nitrogen (78 percent), oxygen (20.9 percent) and argon (.9 percent).

Less than .05 percent of the atmosphere is made up of greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide and methane. These gases absorb and then re-emit heat from the sun to keep the planet at a livable temperature. Because these gases make up such a small proportion of the atmosphere but play such a large role in regulating Earth’s surface temperature, human activity like burning fossil fuels can and does have a global impact.

Before the industrial revolution, carbon dioxide levels were about 280 parts per million. Today, they have surpassed 400 ppm — the highest in at least 800,000 years.

And just as a two-degree temperature shift can mean life or death for a shrimp, changes to global temperature that appear slight can have far-reaching consequences.

Earlier this year, scientists at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies announced global temperatures in 2018 were 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than the "baseline" period of 1951 to 1980. The past five years are, collectively, the warmest in the modern record, they said.

“2018 is yet again an extremely warm year on top of a long-term global warming trend,” GISS Director Gavin Schmidt said in a statement at the time. “The impacts of long-term global warming are already being felt — in coastal flooding, heat waves, intense precipitation and ecosystem change.”

Most excess heat and greenhouse gases are absorbed by the world’s oceans, which are growing warmer and more acidic as a result. Ice sheets are melting and sea levels are rising. Major currents, like the Gulf Stream, which brings warm water up from the tropics past Georgia on its way to the North Atlantic, are slowing and possibly shifting course.

These and other changes are affecting climate and weather systems around the globe. On Georgia’s coast, that includes changes in water temperature, salinity and oxygen levels in the estuaries that are home to countless species, including shrimp.

“For me, climate change is not about polar bears or the year 2080 — it is about issues affecting the daily lives of all of us right now,” said Dr. Marshall Shepherd, director of the Atmospheric Sciences Program at UGA. “This is one of them. We eat shrimp, and hard-working people rely on them for their livelihood.”

A disappearing way of life

Georgia’s shoreline once teemed with shrimp boats, mostly small, family-owned wooden trawlers.

“It looked like a city out there,” said Puterbaugh of the Georgia Shrimp Association. “Now, if you see ten boats it’s crowded. That’s how much it’s changed.”

In 1979, there were 1,471 licensed shrimp boats. Last year, the state issued permits to just 258. Some of the same families remain in the business, but most of the small crafts have been replaced by larger, more expensive boats and about a third of licenses were given to non-Georgia residents.

The decline of the local shrimp industry is largely due to economic factors. The cost of maintaining and fueling a boat is high, and dock prices for wild caught shrimp are comparatively low. Consumers have grown accustomed to paying bargain prices for cheap farmed shrimp, mostly imported from Asia.

But some say the shrimp crop has also become more unreliable because of black gill.

“This is not a minor problem,” said Mike Sullivan, who has been shrimping off the Georgia coast for 52 years, since he was 14. “This problem is killing millions of pounds of harvestable shrimp.”

Georgia wildlife officials are cautious in their assessment of black gill’s impact on the industry.

“I don’t think it’s good, but I’m not terribly concerned it’s going to collapse the fishery,” said Leonard, the DNR biologist.

Some of the shrimpers who spoke to The AJC were wary of the proposed connection between climate change and black gill in Georgia. They speculated the prevalence of the parasite could be caused by chemical runoff, contamination from farmed shrimp or changes to the ecology of the sounds since they were barred from trawling there in the late seventies.

But they also say they have seen changes that seem to fit a broader pattern.

“I’ve noticed, over the past ten years, that it seems like the best shrimp production is occurring further and further north,” said Bill Harris, who owns two 75-foot trawlers and manages a dock in Townsend. “Our falls have been faltering and the black gill settling in, while further north that traditionally had no white shrimp season at all are just logging these phenomenal landings.”

Pat Mathews, a third generation shrimper, said when he first started seeing black gill, it would only appear in white shrimp in late summer. Then it began showing up in brown shrimp in June. This year, he found it in roe shrimp as early as May.

“It definitely flourishes when the water temperature peaks,” said Mathews. “If this black gill goes away, we’re liable to all be doing good. Back like it used to be.”

But to Frischer, the microbiologist, black gill is more likely a harbinger of things to come.

“It’s a canary in the coal mine, and it’s not the first,” he said. “There are many emerging diseases, all over the planet, in both marine and terrestrial organisms, that are clearly being affected by climate change.”

Data specialist Nick Thieme contributed reporting to this story

Our reporting: For this story, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution spent time aboard the Research Vessel Savannah with scientists studying black gill, which has reached epidemic proportions in shrimp off the coast of Georgia. We also spoke to wildlife officials and shrimpers who have struggled to find common ground when it comes to black gill and its impact on fisheries.