White parents, it’s time to talk about race

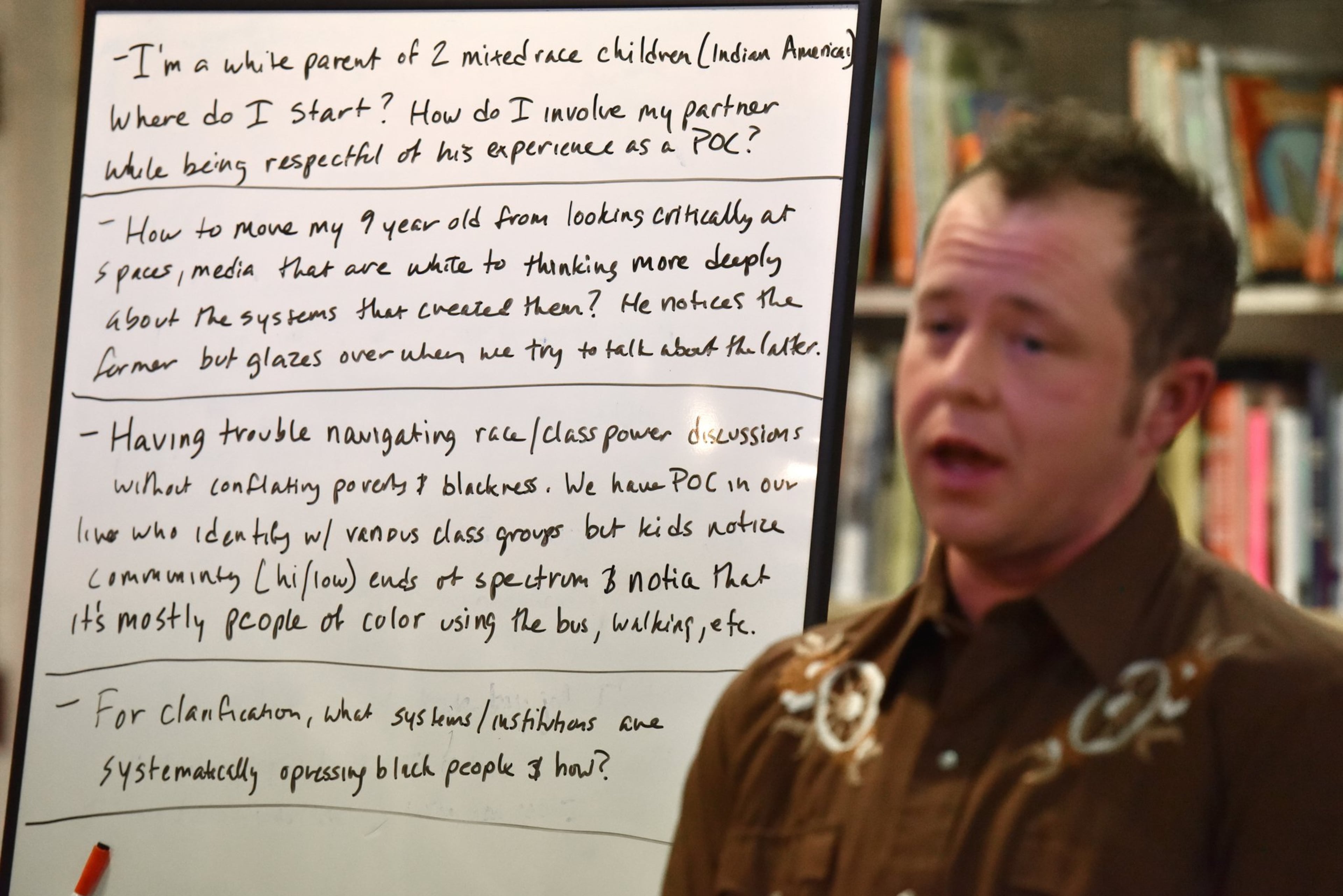

More than a dozen white parents sit in a circle at Charis Books and More in Little Five Points.

Many of their children are barely beyond the age of reading “Goodnight Moon.” A few are parents of preteens and teenagers.

Reading, though, is not the topic of conversation.

Instead, they’ve gathered to discuss the thornier issues of race and privilege.

How do you talk to very young kids about race?

My brown son does not want to be brown in our white family.

My brother-in-law is a police officer. How do we talk about our son when police are accused of doing bad things?

How do I talk about white privilege?

The parents, who meet once a month, are part of the Race-Conscious Parenting Collective, which launched a year and a half ago in response to the 2016 police shooting death of Philando Castile in Minnesota. Other such groups exist locally and around the nation.

“We heard from the people of color in our community that one of the ways that white people could be helpful and useful was to work on our internal white supremacy in our families and our communities,” said co-facilitator E.R. Anderson, executive director of Charis Circle, the nonprofit programming arm of Charis Books and More. Anderson is white.

Related: Every American has been touched by Linda Brown

In other words, white people needed to put in the work, too.

Conversations about race are commonplace among families of color. Many black parents even have a name for it — the talk.

- What should you do if you're stopped by police?

- What if you are the only black student in class?

- You have to be twice as good as whites to get half of what they have.

“We think white people need to catch up,” said Anderson, whose partner has a teenage daughter. “White people still talk about race like it’s a taboo subject like sex. Parents of color talk about it as a pragmatic issue.”

Those conversations have become even more important given the racial divisiveness in the nation today.

After the 2016 presidential election, for example, the bookstore was packed with more than 100 parents attending the collective meeting. The meetings usually draw 20-40 people. It’s largely white, although once in a while, a parent of color will attend.

“Young children notice differences and ask questions, and often it is the parent who is uncomfortable responding,” said Beverly Daniel Tatum, president emerita of Spelman College and author of “Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? And Other Conversations About Race.”

Tatum tells the story of her then-3-year-old son who once told her that Tommy, a white classmate, said his skin was brown because he drank a lot of chocolate milk. (Her son is now an adult.)

Related: Let's talk about privilege

Related: H&M apologizes for posting black child model in "coolest monkey" hoodie

She explained to her son that his skin was brown because he had more melanin than his classmate.

When she asked the teacher how she was handling the question and who was “setting Tommy straight,” she responded that the issue hadn’t come up.

“It was coming up, but not in her hearing,” said Tatum. “It was coming up in the sandbox and the snack table. The fact is that adults become so anxious about these conversations that they try to hush the child instead of giving them an explanation they can understand. White privilege is not easily explained to your child, but every child understands fairness and what’s unfair.”

During the meetings, people discuss questions their children might be asking about race. Several are white parents who have adopted black children or whose children are biracial.

One woman said her son wanted to know why he didn’t look like his white father. Another wanted to know how to help her child deal with family members who are not as accepting of racial differences.

It’s important to address the issue in an age appropriate way. The group hopes to give them to tools to do so.

Don’t ignore race.

Shannon Gaggero, author of the blog “A Striving Parent,” had always considered herself an ally and advocate for racial justice. She was outraged at the shooting deaths of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown.

She could point to many examples of the myth of a post-racial society, “yet my life continued on as normal, wholly unaffected. I felt sadness, yes, some frustration at the state of our country, but to be honest, the thought never even crossed my mind that I was part of the problem or that I could be part of the solution.”

She lived in a predominantly white neighborhood. Her family was white.

Gaggero approached Anderson, a longtime friend, about starting a parenting group at Charis.

Similar groups existed online, but they both thought it would be a good idea for parents to meet face to face.

The mother of two knew she was on the right track when she was reading to her then-3-year-old son and was pointing out the difference in skin tone of the characters. A look of relief spread across her son’s face.

It was as if he wanted to thank her for raising the topic because he had a lot of questions about people in their lives who were of different races.

“He was already noticing race, but he didn’t have any context or framework to understand,” she said.

Donna Troka, who is white, and her partner have a 3-year-old son.

In the months leading up to the 2016 presidential election, Troka, who lives in Decatur, became more uncomfortable with what she saw going on.

“I started thinking about what it means for me to be raising a white male and all that goes with privilege and the ease in which he will move through the world,” said Troka, associate director of the Center for Faculty Development and Excellence and an adjunct professor at Emory University. “We wanted him to use it for good.”

They’ve already started discussing race with him. “I want him to know that it’s not taboo to talk about difference in any way whether that difference is on race, or gender, or sexuality or ability.”

Jonah McDonald, a resident of Kirkwood, has a 3 1/2-year-old daughter and is an administrative director for Peacebuilders Camp, a summer camp for middle school students that teaches them about human rights.

He grew up in an integrated Memphis, Tenn., neighborhood and wanted the same for his daughter in Atlanta.

“I want to learn how to talk about race with my child,” he said. “We can’t change the whole system, but we can change our families.”

And that radiates outward, he believes.

“I actually feel like I’m doing something good for the world.”