Starz, on the heels of its successful scripted Starz series “BMF,” is coming out with an eight-part documentary series on the notorious drug trafficking and money laundering organization.

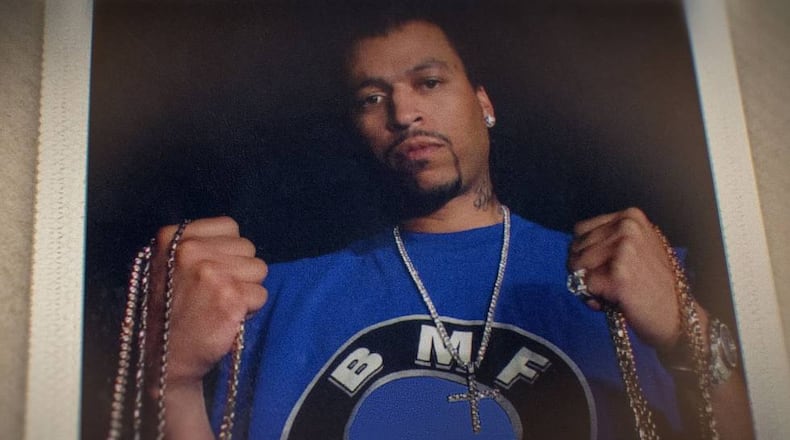

BMF, known as the Black Mafia Family, was started in the late 1980s in Detroit by two ambitious brothers, Demetrius “Big Meech” Flenory and Terry “Southwest T” Flenory, and by 2000 had built a cocaine distribution operation that spanned the nation and operated like a Fortune 500 company. The feds would eventually take them down in 2005 and sentence both brothers to 30 years in prison.

With the scripted version already on air and cooperation from Meech, executive producer 50 Cent decided to create a companion documentary, which is cheekily titled “The BMF Documentary: Blowing Money Fast.”

The documentary focuses on Meech’s time in Atlanta primarily in episodes three, four and five. In the early 2000s, he set up East Coast BMF headquarters in Atlanta and launched an entertainment company to promote rap artists. He and his crew spent gobs of money at dance clubs and lounges, on strippers and champagne, while rubbing shoulders with P. Diddy and Lil Jon.

BMF even put up a billboard in Atlanta (á la So So Def Records) — an arrogant move that annoyed his brother Terry, who ran the West Coast operations — and basically mocked the investigators trying to take him down.

In the fifth episode, Meech declared: “I’m the Black Pablo Escobar,” referring to the infamous Colombian drug lord.

Meech’s heavy partying would eventually catch up to him. At Club Chaos in Buckhead in 2003, Anthony “Wolf” Jones, a former bodyguard of P. Diddy, got rough with an ex-girlfriend hanging with Meech’s crew. Jones got kicked out. Later, when Meech was leaving the club, a massive shoot out happened and two men (including Jones) were dead. Meech was arrested for double homicide. (The doc uses several images of contemporaneous stories from The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.)

Though Meech was eventually acquitted of the charge, the Club Chaos shooting caused a major rift between him and his brother.

Shan Nicholson, who has done documentaries about the Jonestown massacre and 1970s New York City culture, and his other producers were able to convince many former BMF members to speak on the record for the documentary.

“It took a lot of trust building to get them to a comfortable place,” Nicholson said. “Street culture is you don’t speak on camera. You don’t speak period. We had to get over that hump.”

They were also able to get Meech to talk about his experiences via phone, the first time he has spoken to media about his life since he was sent to prison. “To have Meech’s voice in it, to have his own point of view and tell his own stories, this is definitely new ground,” Nicholson said.

Chris Frierson, the director, grew up in Detroit and was well aware of BMF. He said Meech, in the interview, didn’t appear to gloss over his wrongdoings: “He’s at a space in his life that he’s reconciled the good and bad things he had done. He understands his story.”

Nicholson also noted an irony: “As flashy as Meech was, as public as he was, he was the more careful one. Terry was the one caught on the wiretaps, not Meech.”

Terry, Frierson noted, declined to speak to the producers on the record. (He was released in 2020 during the pandemic to home confinement due in part to health issues.)

“He’s never been the camera guy,” he said. “In some poetic sense, you feel his presence in the film but he’s not there” beyond mostly still photos.

>>RELATED: A look at “BMF” the TV series with 50 Cent

And while BMF eventually was dismantled, it operated unhindered for a surprisingly long time, which “is a testament to their business model,” which involved almost no bloodshed.

“They were different than most other criminal organizations,” Frierson said. “We wanted to show their industriousness, their discipline. They made deals with people all over the country and were fair with them... BMF transcended gang colors and affiliations. It transcended race and creed. This organization had people of all walks of life.”

But at the same time, “it’s important to note this empire was built on pain, on drug addiction.”

Frierson also understood why Meech left Detroit in the first place for Atlanta, where Black folks with money were not looked at with as much suspicion as they were in Detroit. “Atlanta was called a Black mecca for a reason,” he said.

But the Club Chaos shooting drew so much attention, he noted, in part because it happened in the wealthy enclave of Buckhead. Frierson, while in town, noted that even two decades later, crime in Buckhead seems to get an inordinate amount of attention from the press and police.

Ultimately, Frierson said this documentary is like a twisted, relatable American Dream story. “BMF was borne out of a lack of opportunity,” he said. “They made choices at first to just feed their families. Then it became much bigger.”

ON TV

“The BMF Documentary: Blowing Money Fast,” 10 p.m. Sundays on Starz starting Oct. 23

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured