Antonio Bryant has lived through 15 years of chronic homelessness, which occurred in periodic episodes beginning in 1987 after he returned home from the Army. A drug habit, fueled by PTSD and mental illness, landed him in and out of jail, on and off drugs and with and without housing.

Bryant, a native of southwest Atlanta, had left home to escape an environment of alcoholism and poverty, but throughout his life, the very influences he was running from kept pulling him back.

“I was living in the streets … doing whatever I needed to do to make sure I ate and was able to get my drugs,” said Bryant, 58. “I didn’t know what was wrong with me … all I know is I had problems.”

Last fall, Atlanta police officers picked him up for possession of drug paraphernalia, but they turned him over to the Policing Alternatives and Diversion Initiative (PAD).

Bryant currently resides in a sober living house and has become a peer mentor for PAD but has yet to find permanent housing.

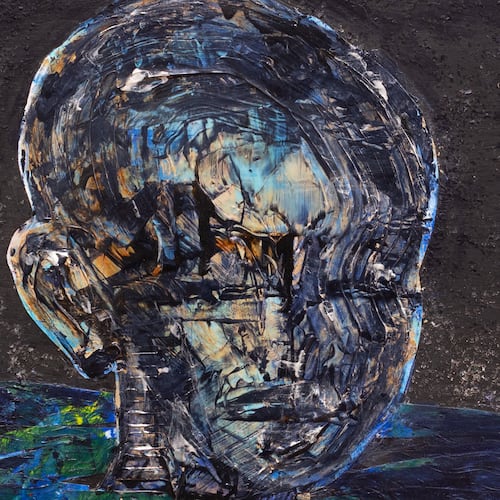

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

“Getting permanent housing is a wait. You have to cross your I’s and dot your T’s,” he said, referring to documentation that has taken several months to acquire. But one of the biggest challenges of being homeless for Bryant was accepting that he needs the help. “I was always independent, self-sufficient. I took care of myself one way or another,” he said. “When I got arrested in December ... I made up my mind to let them help me.”

Now, Bryant is on a mission to help others who are unhoused accept the help they need and to give other people a better understanding of homelessness in Atlanta. “The biggest thing people don’t understand about homelessness is why,” he said. “Getting situated and getting my own housing means getting back to a normal life.”

There are an estimated 3,200 sheltered and unsheltered people experiencing homelessness in Atlanta, including people living on the street, in emergency shelters, transitional shelters, and in the non-congregate shelter hotel leased as part of the city of Atlanta’s COVID-19 response.

Many more people in Atlanta, like in most cities in the United States, are at risk of homelessness because of an extreme shortage of affordable housing, limited opportunities for living-wage jobs or other stable basic income, and an inadequate social safety net.

Addressing the problem first requires understanding the problem, so I asked local experts from the PAD initiative and Partners for HOME, the lead agency for a local collaborative that coordinates assistance for homeless families and individuals and works to end homelessness in Atlanta, to answer a few questions about a population that so many of us know so little about.

Q: What is the definition of homeless or unhoused?

A: According to the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), people who are homeless or unhoused are people who are living in a place not meant for human habitation, in emergency shelter, in transitional housing, or exiting an institution where they temporarily resided; people who are losing their primary nighttime residence (which may include a motel, hotel, or living with family, friends, or other non-relatives) within 14 days and lack resources or support networks to remain in housing; families with children or unaccompanied youth who are unstably housed and likely to continue living in that state or people who are fleeing or attempting to flee domestic violence, have no other residence, and lack the resources or support networks to obtain other permanent housing.

Q: How many beds/housing options are there for the unhoused population in Atlanta? Is that enough?

A: There are hundreds of private and publicly funded emergency shelters serving the city of Atlanta, which provide a total of 2,756 beds. Transitional housing programs provide temporary living spaces for six to 24 months and other supportive services. There are 1,022 transitional housing beds available in Atlanta. Emergency shelter provides short-term housing, and there are 1,734 emergency shelter beds in Atlanta. Both emergency and transitional sheltered beds are often not filled to capacity for a variety of reasons. Access to permanent housing is the most effective solution to homelessness and is what reduces a return to homelessness.

Q: Why do some unhoused individuals not want to go to shelters?

A: Living unsheltered isn’t easy, but it does allow people some control over their own lives. In shelters, people may face strict rules and curfews, with additional restrictions for those with addiction or mental health challenges. If you work a night shift that keeps you out past curfew, or have a beloved pet that is not allowed, these types of rules can be prohibitive. Additionally, like anyone else, many unhoused people don’t want to live alongside people they don’t know, trust, and may even fear. They may also have strong ties to the neighborhoods they’re currently residing in, with connections to friends, family, jobs, schools, or places of worship. All of these concerns are intensified during a pandemic, when sleeping in close proximity to others presents significant health risks and people are worried about contracting COVID-19 staying inside.

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Q: What is the appropriate response to homeless encampments?

A: Some community members express concerns about people who are living together outside in tents or other semipermanent structures. However, shutting down homeless encampments often just pushes people from one location to another, and in the process, disrupts the connections and resources they may have. Clearing encampments also intensifies the distrust unhoused individuals may feel toward social service providers, making it harder, not easier, to connect them to services. A better approach includes consistent, dedicated and skilled outreach teams to engage individuals living in encampments with the goal of connecting people into permanent housing solutions. This process can take three to six months of active engagement to build trust and rapport with someone living outside before they are willing to consider housing options.

Q: What should I do if I need assistance responding to a person who appears in need of immediate support related to homelessness, mental health or substance use?

A: If you need assistance addressing a concern related to extreme poverty, unmet mental health needs, or substance use, you can make a referral to the city of Atlanta’s nonemergency 311 line (if in the city limits) or 404-546-0311 (beyond city limits). The ATL311 team may refer you to a harm reduction team with the Policing Alternatives and Diversion Initiative (PAD), who will conduct outreach with the referred individual and offer immediate support and connection to other resources. If a person appears to be in need of immediate medical assistance, call 911.

Q: Should I give money to people experiencing homelessness?

A: More important than any one person’s decision to give is how people respond to requests for help, and that whether the answer is yes or no, it’s communicated with respect and decency. Consider what it means to any of us to be looked in the eye and treated like a human being, not ignored as if we don’t exist. This neighborliness and grace is an important part of together addressing the challenges of homelessness.

Read more on the Real Life blog (www.ajc.com/opinion/real-life-blog/) and find Nedra on Facebook (www.facebook.com/AJCRealLifeColumn) and Twitter (@nrhoneajc) or email her at nedra.rhone@ajc.com

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured