OPINION: Does reading banned books negatively impact young readers?

Last spring, Noelle Kahaian stood before the Georgia Legislature and read a passage describing a rape scene from “The Handmaid’s Tale.” The 1985 novel by Margaret Atwood set in a fictitious, hyper-patriarchal New England state that has overthrown the U.S. government had been assigned reading at a local high school, and Kahaian, director of Protect Student Health Georgia, was using it to make a point — school districts should not be offering up obscenity to minors.

“These obscene materials trigger abusive memories in traumatized children and teenagers. Exposing them to more harmful materials causes irreparable damage,” said Kahaian in a letter to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution after one of my colleagues wrote about the legislative hearings where Kahaian spoke in support of anti-obscenity legislation. Books like “The Handmaid’s Tale” “glorify sexual assault, rape culture and violence against girls, children and women,” Kahaian stated.

Anti-obscenity legislation, poised to become a priority when the legislative session resumes in January, is the latest page turner in the culture wars of the past decade. But we can’t legislate our way out of coping with personal traumas or discussing concerns related to sex, race, gender identity, violence, politics, religion and other social issues that many challenged books address.

Book banning has been around since the 1600s when the Puritans got peeved at Thomas Morton for his tell-all on their New World practices. The arguments for and against modern-day book bans don’t change much. Supporters — largely composed of organized groups and parents — say they want to protect minors. Detractors — mostly librarians and parents — say they want to protect First Amendment freedoms of all Americans.

If you’re a student of history and if you were an adult in the 1990s, then you’re probably feeling a little bit of déjà vu. “Unfortunately, to my mind, it does feel like the same old thing,” said Wendy Cornelisen, president of the Georgia Library Association. “(The 1990s) also felt like a time with lots of anxiety and change happening in the world. While we may not be anxious about the same things ... we are still living in times of anxious change.”

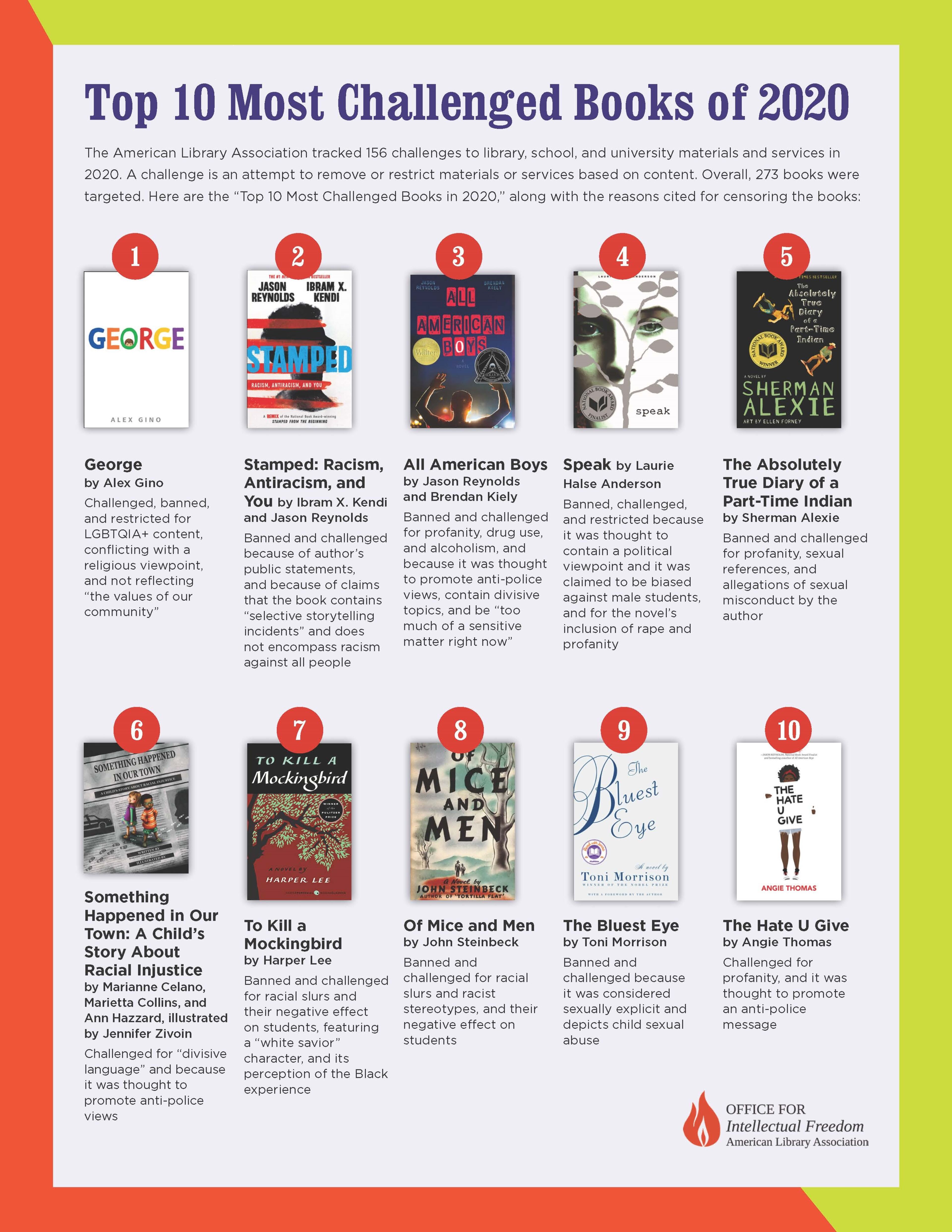

There has been at least one small shift in the world of book banning in recent years. In 2019, 45% of book challenges were initiated by library patrons, and most challenges (66%) focused on books in public libraries compared to only 31% in schools or school libraries. A year later in 2020, when the pandemic forced children across the country to learn from home, the majority of book challenges (50%) were coming from parents. This time, more than 53% of all challenges were focused on books in schools or school libraries compared to only 43% in public libraries, according to data from the American Library Association.

But for all of these book challenges, there is surprisingly little research on exactly what impact reading a banned book might have on a young person. “People panic and think if you are exposed to this thing, whether you are a child or an adult, and you read this book ... suddenly this will have a dramatic impact on a person that reads it,” said Christopher Ferguson, a professor at Stetson University in DeLand, Florida, whose research on banned books appeared in a 2014 publication of the American Psychological Association.

Most research on the impact of media on young people has focused on television shows and video games rather than books. One of the reasons for the limited research on the impact of books is that it’s harder to measure than other media formats since books are read over time. Interest in the impact of books on psychological well-being also waned in the 1950s as the field of psychology became more focused on observation and experimentation than theory, Ferguson said.

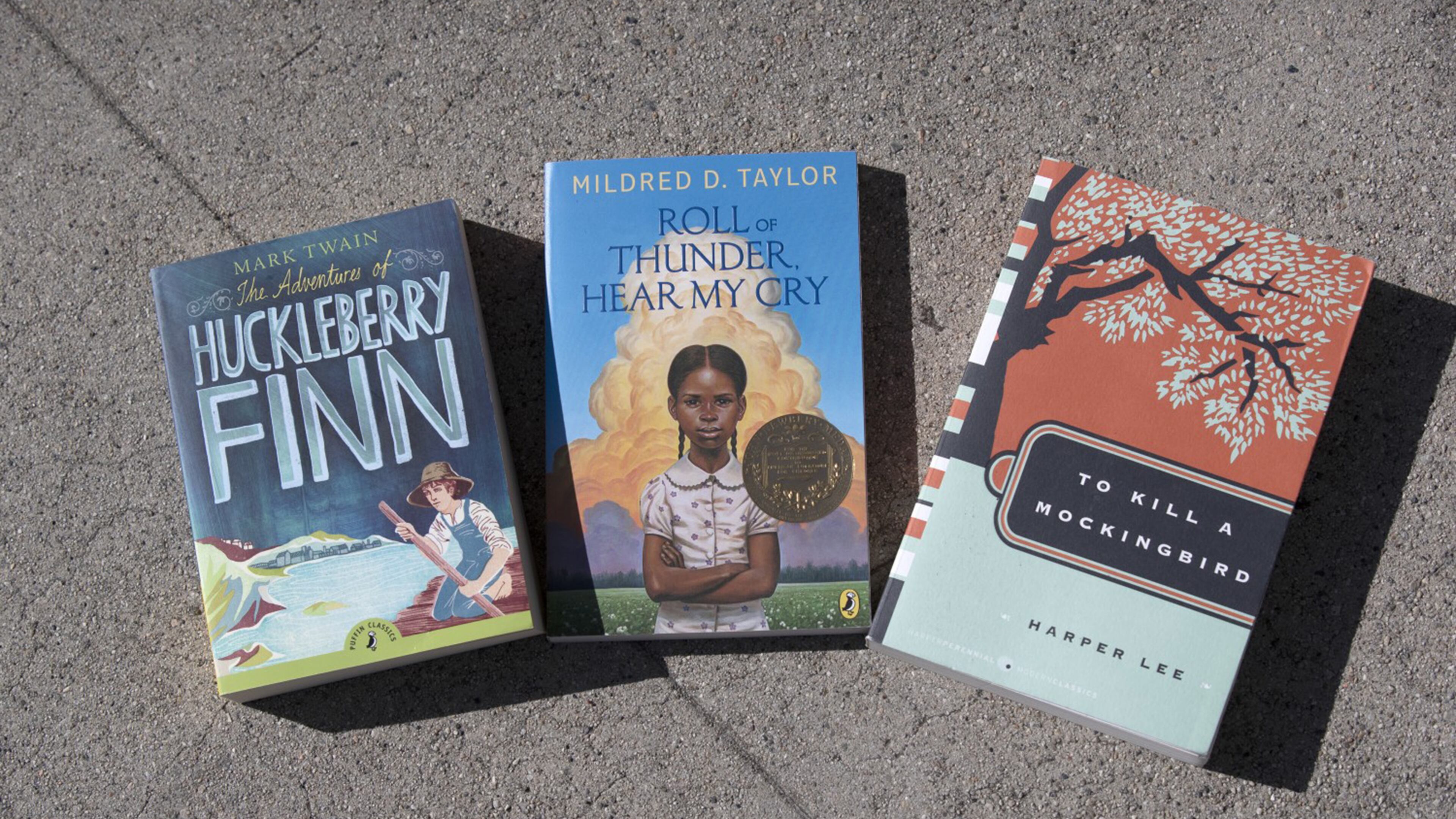

In the correlation study conducted among 282 students ages 12 to 18, Ferguson looked at commonly challenged books ranging from “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” to the “Harry Potter” series to determine if kids who read them were any worse off. “I was trying to see if there was evidence for the belief that reading a banned book was going to have a detrimental impact,” he said.

Ferguson found that reading banned books did not correlate with committing violent or nonviolent crimes. By contrast, reading banned books correlated positively to civic behavior — students were more interested in politics and elections and more involved in charitable causes. Student GPA correlated positively to hours spent reading for personal pleasure (though not specifically reading banned books). A small group of girls who were voracious readers of banned books also had high levels of mental health problems, Ferguson said, but it was unclear whether they were attracted to the books because of the state of their mental health, if their mental health changed because they read the books or if there was a positive or negative impact on their mental health from reading banned books.

More extensive research on the topic might offer greater insight into the statements made by Kahaian and others suggesting that obscene materials in books could trigger girls who have experienced trauma. As Ferguson posits, what if a child’s motivation for reading banned books is more critical than the content of the books themselves?

He is aware that almost any research on the topic will be questioned. “If you say there is no evidence that things are harmful, they will say you have no evidence that it is not,” Ferguson said.

That back and forth was illustrated last month when Virginia’s Spotsylvania County schools overturned a ban on all “sexually explicit” books from its libraries just a week after passing the ban.

But as one local librarian said at the time, “If you have a worldview that can be undone by a novel, let me suggest that the problem is not the novel.”

We are in the midst of what could be a meaningful moment of cultural and social change. Arguments over books will only serve to distract us from substantive action.

“Somehow, we need a huge national reset,” Ferguson said.

Read more on the Real Life blog (www.ajc.com/opinion/real-life-blog/) and find Nedra on Facebook (www.facebook.com/AJCRealLifeColumn) and Twitter (@nrhoneajc) or email her at nedra.rhone@ajc.com.