The Christmas story revolves around arduous travel and makeshift housing in improvised surroundings. On top of all that, there are threats of death from those in power.

It’s an unfamiliar story to Anand Sawlani and Kiran Nawani, husband and wife from Karachi, Pakistan, who grew up Hindu in a majority Muslim city.

But there are echoes of the old narrative in their lives. Threatened in Karachi, robbed and forced from their livelihoods, they traveled to the U.S., only to be separated immediately upon their arrival in the United States. Nawani found herself shivering all night outside the Los Angeles airport, while her husband was held in detention.

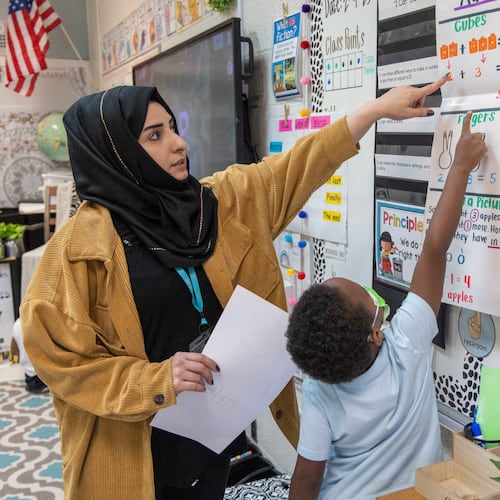

And they’ve struggled to find a place in this new world. Today, as they study ESL classes and wait for their work permit applications to gain approval, they are housed temporarily in a retrofitted Sunday school classroom at Columbia Presbyterian Church in Decatur.

Credit: Ben Gray

Credit: Ben Gray

Pastor Tom Hagood and wife Susan Hagood and many volunteers have helped the couple get to classes, to medical care and job counseling.

“They are parents to us,” said Sawlani, 44, one recent afternoon, sitting in the sunny room he shares with Nawani, their clothes hung on a portable rack, their dishes laid out near a hot plate and a new refrigerator. “They support us when we were in a bad situation.”

The small church, still recovering from the COVID-19-era postponement of in-person services, actually hosts five asylum-seekers, including immigrants from Venezuela, Jamaica and Cuba, with one from Nigeria waiting for an open room.

The visitors are tucked into spaces that were once used for a nursery, an associate pastor’s headquarters, an office manager’s cubicle and storage space.

It’s a significant commitment for a church with about 100 members, but the church leadership and the congregation decided the effort was part of the church’s mission.

Credit: Giuseppe Parra

Credit: Giuseppe Parra

“It’s helping the least of these,” said church member Stuart Miner, a former elder who helped put in the plumbing for one of the two showers that the guests share.

Sawlani and Nawani are grateful for the help, and say they even have a friend who drives them to Sikh services in Norcross. Nawani said the only thing they miss is being able to buy the spices they love.

Church members installed window air conditioners and vent fans for hot plates. Members of a half-dozen other churches contributed funds to buy refrigerators, beds, a washer and dryer and other furniture.

“I’m glad to be able to help where we can; it’s a worthwhile project,” said long-time church leader and elder Bob Reardon, who can often be found on a ladder with a portable drill in hand, fixing old fascia boards or creaky gutters in the aging building.

Efforts to help the Pakistani newcomers and their colleagues are part of the mission of the New Sanctuary Movement, a loose coalition of churches and other organizations that assembled during the Trump administration when Georgia law and national policy became stacked against asylum-seekers and undocumented immigrants.

The original idea was that asylum-seekers in danger of being deported could find protection in churches, where ICE agents were theoretically forbidden to tread.

“That was the big question: were churches truly off limits?” said Miner. “Some thought, yeah, no one’s going to set foot in a church. Other people said, when push comes to shove, it’s just another building.”

Credit: Ben Gray

Credit: Ben Gray

Then there was the question whether an asylum-seeker, once inside, couldn’t come back out, without risk of arrest. This didn’t happen at Columbia.

Due to extensions on their visas, Sawlani and Nawani are free to come and go. Venezuelan Giuseppe Parra, 22, who has been at the church off and on since 2018, has a work permit, and buses dishes at a Mexican restaurant.

Rajhon Whyte from Jamaica has become a certified nursing assistant while at the church and is working at a Wellstar facility.

In 2010 the Georgia Board of Regents banned undocumented students from attending the top five public universities, which prompted a resistance organization called Freedom University. The group has organized protests at board of regents meetings (including one documented by comedian Jordan Klepper) and raises money to send immigrants to private schools tuition-free.

The New Sanctuary Movement works in tandem with Freedom University. The purposes of the New Sanctuary Movement have changed over time. Most agree that in Georgia the chances that a case will be resolved in favor of those seeking asylum are slim to none.

Fewer than 1 in 10 asylum claims were approved in Georgia between fiscal years 2016 and 2021, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a research organization that monitors the government.

Rather than hide out and wait, sanctuary apartments such as those at Columbia Presbyterian are better used as transitional housing. Asylees seek education, take counseling, earn a work visa, get legal help, while members of the New Asylum Movement lobby to get laws changed.

The New Sanctuary Movement also attempts to help refugees who are living in straitened circumstances, helping to pay for lodging and training.

Rev. Jonathan Rogers, a Unitarian Universalist pastor and a key member of Atlanta’s New Sanctuary Movement, said the Christmas story should guide us in our interactions with those seeking asylum.

That chronicle is “such a familiar and yet profound representation and illustration of our duty as people of conscience,” said Rogers, “as folks who seek to live into the values of humanitarianism, and respect for other people’s dignity and worth, regardless of their status, regardless of their being born in a barn, surrounded by farm animals, or if they are coming into the U.S. without citizenship status.

“One of the fundamental parts of what it means to be a good, moral, caring, compassionate person,” he said, “is to extend that generosity — treating a stranger as yourself, loving your neighbor as yourself.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured