Tammy Ozier knows the story of how one of her ancestors risked his life to rescue his two sisters from enslavement.

She just hopes the tale is true.

As the family legend has it, Ozier’s ancestor, Hillery Bibbens, joined the Union Army’s regiment for Black soldiers in Missouri, most likely the 1st Missouri Colored Infantry, around the start of the Civil War. Bibbens wanted to fight slavery, but he also wanted to save his two sisters from its clutches deep in Louisiana.

The historical record says the 1st Missouri deployed to Port Hudson, Missouri. Family lore says he rescued his sisters. Ozier has found the paper trail that might prove the latter to be ambiguous, at best.

“Maybe he didn’t save them, or maybe he found one and not the other,” said Ozier, president of the Atlanta chapter of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society.

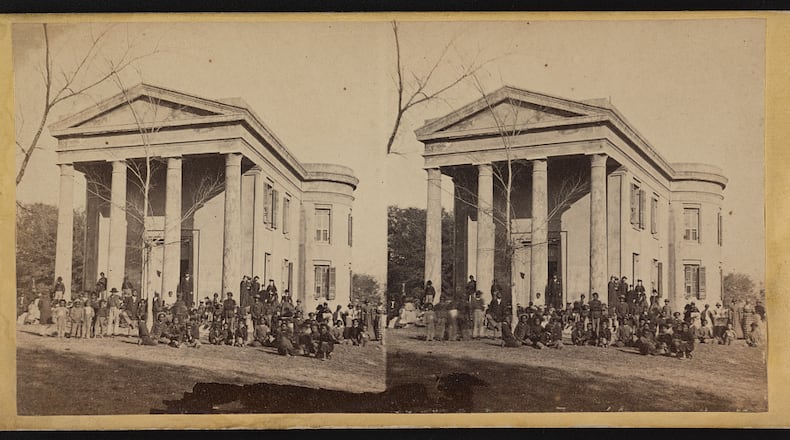

Credit: National Archives

Credit: National Archives

But Ozier is hopeful a newly revamped resource might help not only her gain clarity, but provide answers for thousands of other Black people. She’s just one of many seeking details about their forebears not only during Reconstruction, but also during the final years of slavery. Using nearly 3.5 million documents from the National Archives and Records Administration, Ancestry.com has put together what it claims is the most comprehensive digital index of records from what’s known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, the federal agency charged with helping millions of Southern Black people adjust to lives of freedom after the Civil War. While the original handwritten bureau records have been available and digitized by the National Archives and genealogy resources such as FamilySearch for years, even trained historians found the records difficult, if not confounding, to search because of the labyrinthian way they were organized by topic and location.

Credit: Rick McKay/Cox Newspapers

Credit: Rick McKay/Cox Newspapers

That Ancestry has combined the entire collection of documents — including land records, labor contracts, court disputes, banking records, marriage licenses, schools, even food and clothing rations — and made them searchable now by keyword or name, represents a significant shift in the way people will be able to readily access a critical moment in the nation’s history, historians say. The service will be free, according to a company spokesperson.

“It’s hard to overstate how important this could be,” said Stan Deaton, senior historian with the Georgia Historical Society, who was not involved in the Ancestry project. “The Freedmen’s Bureau was the first effort of the federal government to improve the lives of its people, and in many ways was the first social service agency. So (the Ancestry project) is very important in capturing the lives of 4 million people who were newly freed and starting new lives in one of the greatest social changes in this country’s history. This could be a gold mine.”

‘Huge Record Group’

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands was approved by Congress in 1865 as a mechanism to help rebuild the South after the war. Staffed primarily by the military, it was designed to serve both white and Black Southerners who were impoverished in the conflict’s aftermath. People needed the basics such as food and clothing, but also education and codifying of marriages often legally forbidden for Blacks during slavery. Offices or bureaus were set up in 15 Southern states, including Georgia, in cities and multi-county districts that reported to state headquarters and, in turn, the national office. The Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, was a bank system set up the same year, specifically for emancipated Black people. Though some whites did use the bureau, its primary patrons were the newly freed. That fact frequently made Freedmen’s offices targets of white vigilantes.

Credit: Courtesy Ancestry.com

Credit: Courtesy Ancestry.com

The Bureau’s records document all of this from 1865 to the dissolution of the Bureau in 1872 at the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of legal segregation. What archivists and scholars say makes the documents, and their new accessibility, significant is that they record the names of Black people across the South who sought the bureau’s help, a full five years before the 1870 U.S. Census, which was the first to record the full names of those who had previously been enslaved. Enslaved people, generally, were not counted in previous censuses. That is the roadblock millions of Black people face when searching for their roots in the country. The bureau records have the potential to fill in that gap for some families, but are more likely to provide a more general but more clear picture for students, scholars and laypeople about what that period of time was like.

Before the Ancestry digitization, which began in 2005, people could only search category by category, such as labor disputes or marriages, and they would have to go state by state, county by county or city by city. You can find it at ancestry.com/freedmens.

Credit: ASSOCIATED PRESS

Credit: ASSOCIATED PRESS

“This is a huge record group,” said Tamika Strong, an archivist, librarian and member of the Atlanta Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society chapter. “I was talking to a friend who did genealogy for 30 years and she said it used to take her months to find one person in a census record. Now, think of someone sitting at the National Archives for weeks looking for a name. But now, if that search will only take seconds, that’s golden.”

Strong said she is not a part of the Ancestry effort, but years ago did help transcribe some Freedmen’s Bureau records for FamilySearch.

Ozier is unsure if the records will provide confirmation of the Bibbens story, yield a tantalizing lead, dash all hopes or leave more questions. But she’s looking forward to continuing the search.

“Our ancestors want us all to be reunited, by any means necessary,” said Ozier. “This will allow greater access to the paper trail.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured