In art history, women tend to be depicted in conventionalized ways: as sirens and vamps, mothers and madonnas, embodiments of human vanity and human vice — empty vessels for male artists to dump their own prejudices into.

When female artists tackle self-portraiture, their vision of femininity is blessedly revisionist.

Steeped in authenticity, messiness and seemingly devoid of vanity, photographer Nancy Floyd’s black-and-white self-portraits in her new book “Weathering Time” (GOST Books / PhotoEye Books, $55) are frank, endearingly straightforward images that counter the art history tradition of woman-as-metaphor.

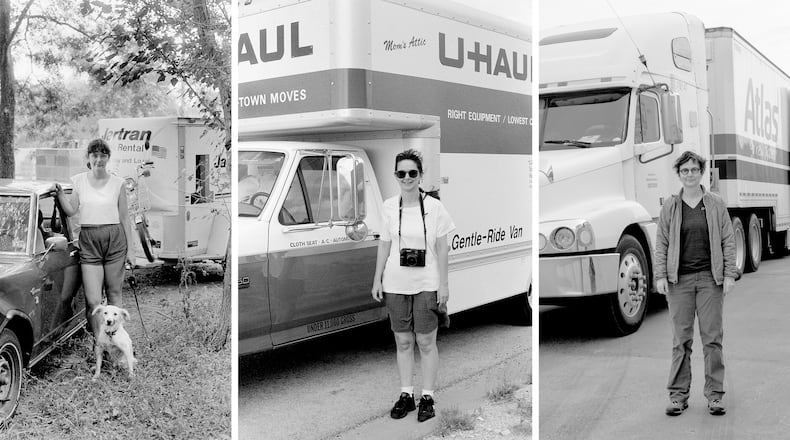

The project began in 1982, the summer after she graduated from the University of Texas at Austin and has now ballooned to more than 2,500 images. In “Weathering Time,” Floyd, 64, divides her life into chapters of sorts: “Good Hair,” “Shirts With Words,” “Fitness” (Nancy in exercise gear or standing in her CrossFit gym), the epic “Shorts” and “Dresses” (a very brief chronicle), showing the patterns that define her life.

In side-by-side photos, Floyd charts the passage of time as the long luxuriant rope of hair reaching to her rib cage is replaced by a practical cropped cut. They capture her transitions as she moves out of League City, Texas, the origin story of her working-class parents and five siblings, marries, becomes an artist with a studio at Atlanta Contemporary and discovers the joys of backpacking.

“When I started this project,” she says, “I was already disgusted with the way women were being represented in advertising or even in the art world. I wanted to create a work where my body wasn’t objectified in a sexual way.”

Credit: Nancy Floyd

Credit: Nancy Floyd

Shooting on film pretty much took vanity out of the equation. “Because the rolls of film weren’t processed that often, I really didn’t know what I looked like, so I couldn’t really fix myself,” she says. “I think there was a beauty in not having the instant gratification of a selfie.”

The concept of the selfie looms large over “Weathering Time.” Floyd’s self-portraits are to the selfie what straight bourbon is to a wine cooler: adult, serious and not idiotic. In a contemporary life filled with fetid, self-promotional, filtered selfies that freeze daily life in an aspic of curated perfection, “Weathering Time” is like a gust of fresh springtime air. The project revels in the bald, unfiltered truth and the bracing, often painful reality of life beyond the sunny, delusional borders of Instagram.

“Sometimes when I’m setting up the camera I’ll think, ‘Man, this is a messy room,’ or, ‘I’m wearing my sweatpants for the fifth day in a row,’” Floyd says.

But she takes the photo anyway.

In one series of images titled “Underwear,” she poses in her defiantly unsexy white cotton underwear beginning in her 20s and through her 60s. She’s interested in how those half-dressed self-portraits will evolve as she continues to age.

“I’ll probably take more pictures of me in my underwear because I know my body is really going to start changing now. I’m curious about the body,” she says, as if describing a conceptual project rather than her own flesh. But “Weathering Time” is both: academic and deeply personal.

“I think of this project as sort of my performance,” she says. “And if I’m true to it, I’m going to allow you to see things that maybe I wouldn’t show people normally.”

Credit: Nancy Floyd

Credit: Nancy Floyd

A gentle, mild-mannered artist dulcet of voice, with dark, kind eyes that glisten with curiosity, Floyd called Atlanta home for 22 years. She nurtured generations of Georgia artists as a professor at Georgia State University but in 2018 moved to the high desert of Bend, Oregon. Like almost everything in her life, it’s documented on page 164 of “Weathering Time” in the section called “Moving.”

Floyd initially intended “Weathering Time” as a documentation of her own aging process. But over time it has expanded into a profound, often metaphysical musing on time, death, endurance and family.

“For people who want instant gratification, I don’t think my project can do that for them,” she shrugs. “Ho-hum,” she remembers one reader commenting after the work was featured in the New Yorker.

But looking at the entire body of work is a cumulative emotional wallop. “Weathering Time” opens with a picture of a newborn Floyd in a hospital bassinet. On page 221, titled “Loss,” the artist stands next to her mother’s casket about to be lowered into the earth.

Floyd documents both of her parents, Catherine and Bill, gaunt and unrecognizable, on their death beds. There is a series of images of her older brother Jimmy as a little boy. There’s also an image of that same beagle- and gun-loving brother standing bare-chested with a rifle in his hand in Vietnam. Those images are paired with a shot of Floyd looking tired and cold at the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., where her brother’s name is carved into the black wall with the other 58,317 dead: SP4 James Milton Floyd.

The photos are a window into the enduring bonds of familial love. About the images of her mother, Catherine “Kai” Jones Floyd, Floyd writes, “During the last years of Mom’s life, when the photograph of us in the hospital was taken, it was clear my childhood would soon be over. All the gifts and soup that others might provide would never make me well again.”

The images have taught Floyd a lot about her mother’s deep, enduring love. “Looking at the photographs I see the real love my mother had for me,” Floyd says.

Some of the book’s photos are so intimate, it’s often difficult for Floyd to spend time privately with the work. When it’s just a project, exhibited in galleries, everything’s fine.

“When I have a show I really am disconnected when people are asking me about it,” she says. Even when they ask about her mother and father. At home, surveying the images, it’s a different story. “It’s also my journal, my visual diary. It’s basically a portrait of my past. Sometimes I just don’t want to look at them anymore.”

Many of the images feature Floyd in her living room, standing amid piles of clothes in her bedroom or with her husband Robin on their front porch. If the images seem homebound in some ways, there’s a reason. From a young age, she suffered from agoraphobia.

“I was pretty much afraid of the outdoors,” admits Floyd. “I missed out on a lot of things that would have been fun to do. If I could have done them.”

It’s not until she’s in her 40s that we begin to see photos of Floyd in front of a pitched tent in the woods, riding next to Robin on a Segway or on vacation posing in front of Three Mile Island where her nuclear engineer husband once worked.

“Weathering Time’s” snapshots are portals to a universal experience of home, family, love and loss, an especially important connective tissue in these divided times. Her snapshots feel like a ripple across a vast ocean we all gaze upon; the life changes that are sad and happy but which no one can escape.

And she’s never going to stop.

“Curiosity and drive are the most important things you can have,” she says. She’s currently developing work about the starkly beautiful Oregon landscape that will be exhibited at Atlanta’s Whitespace Gallery in October 2021.

And, of course, “Weathering Time” will, like Floyd, carry on. She has left instructions with her husband ― if she is gone before he is ― to capture her on her own death bed.

“I will write it down and say specifically: ‘It’s got to be a vertical. And it can’t be too far away. But it can’t be too close.’”

ART BOOK

‘Weathering Time’

by Nancy Floyd

GOST Books / PhotoEye Books

257 pages, $55,

About the Author

The Latest

Featured