Photographer Al Clayton’s legacy is his daughter’s mission

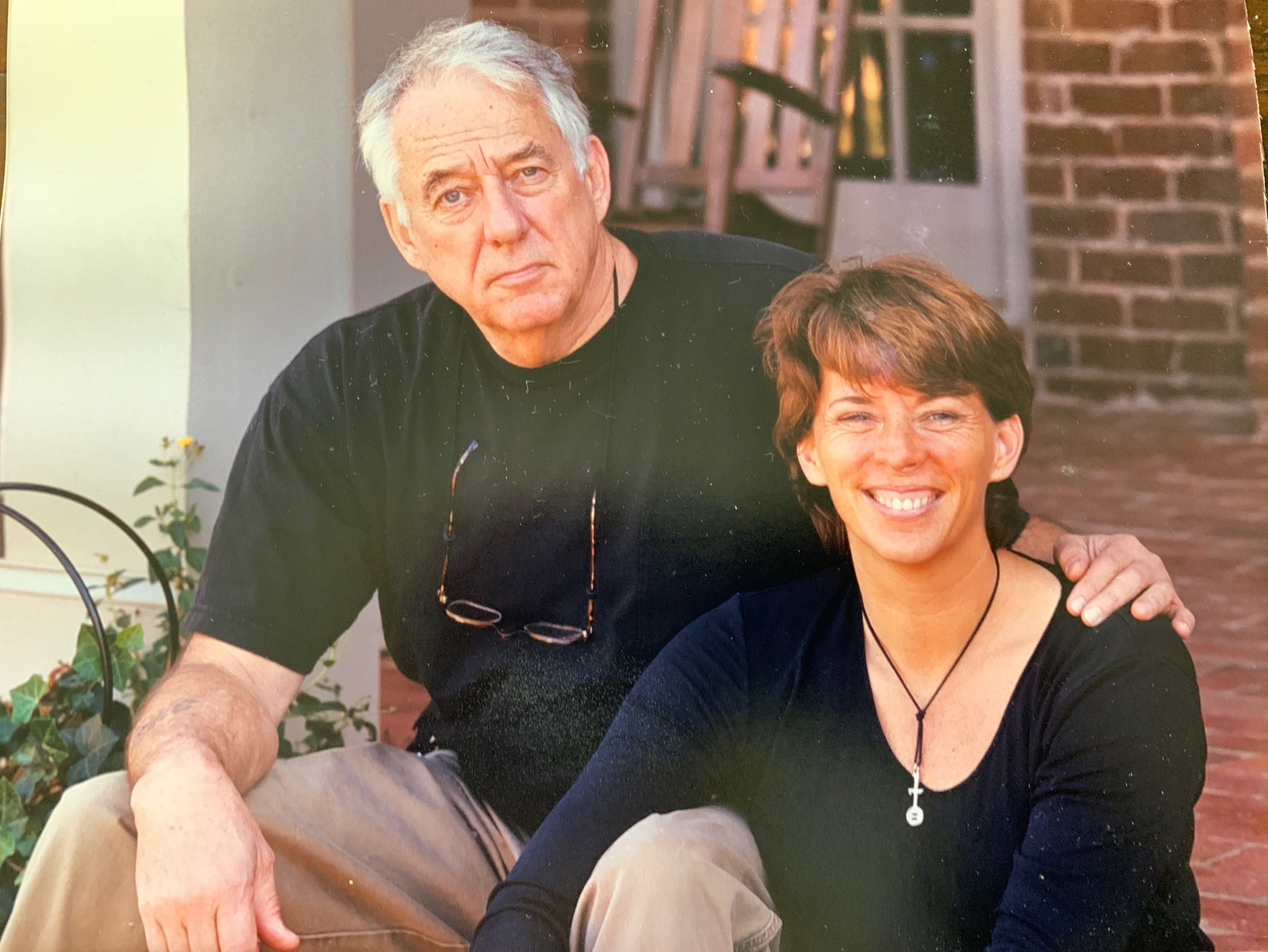

When Atlanta photographer Al Clayton took custody of his daughter in the early ‘70s when she was 10, a bond was forged between them that only grew stronger over time.

It was at that tender age when Jennie Clayton’s appreciation for her father’s photography first took root. In the beginning, they lived together in his Atlanta studio, surrounded by photographs that at any given time might be shots of country music artists on tour, starving children in the Mississippi Delta, decked-out club kids at Backstreet bar or products for commercial clients. He was that rare photographer that produced photojournalism as well as advertisements.

She began assisting him in the darkroom, learning how to process film and listening as he explained his creative process. And when he died in 2014 at age 79, she inherited a career-long collection of photographs and negatives that filled file cabinets and a storage unit.

Looking back over his career, Jennie was reminded of the history her father witnessed: civil war in Biafra, a Ku Klux Klan rally in Stone Mountain, political protests, snake handlers, the early careers of RuPaul, Johnny Cash, Kris Kristofferson.

The magnitude of his estate weighed on her. She couldn’t just let all that work lie dormant and forgotten. She wanted the world to remember his work and to “see what he saw.” So, she decided to make it her mission to preserve his work and keep his legacy alive.

During the last year of Al Clayton’s life, Jennie, who lives in Gainesville, Georgia, began interviewing her father on video. One day she asked him to identify the work he was most proud of producing.

“He pointed at the book ‘Still Hungry in America’ and said, ‘I just hope I made a difference,’” said Jennie. It became the natural place for her to start generating renewed interest.

Published in 1967, “Still Hungry in America” was a grim photographic survey of children starving in the rural South that Clayton produced with text by Robert Coles. Clayton’s images are credited with contributing to the momentum that led to a dramatic expansion of the U.S. food stamp program. First on Jennie’s to-do list was to get the book republished, which the University of Georgia Press did in 2018.

Next, the 59-year-old mother of four secured gallery representation with Morrison Hotel Gallery, which has locations in Los Angeles, New York and Hawaii, as well as Lumiere Gallery in Atlanta, which promptly presented an exhibition of Clayton’s elegiac portraits of homeless people taken in the ’80s.

“A lot of what distinguished his work is Al’s point of view and who he is and what he did with that point of view to turn the tables on society and help the people that were downtrodden,” said Tony Casadonte, director of Lumiere Gallery. “There’s an overarching humanity to it. The ones that are particularly heart-wrenching are hard images to live with, but he did it in a way that captures humanity.”

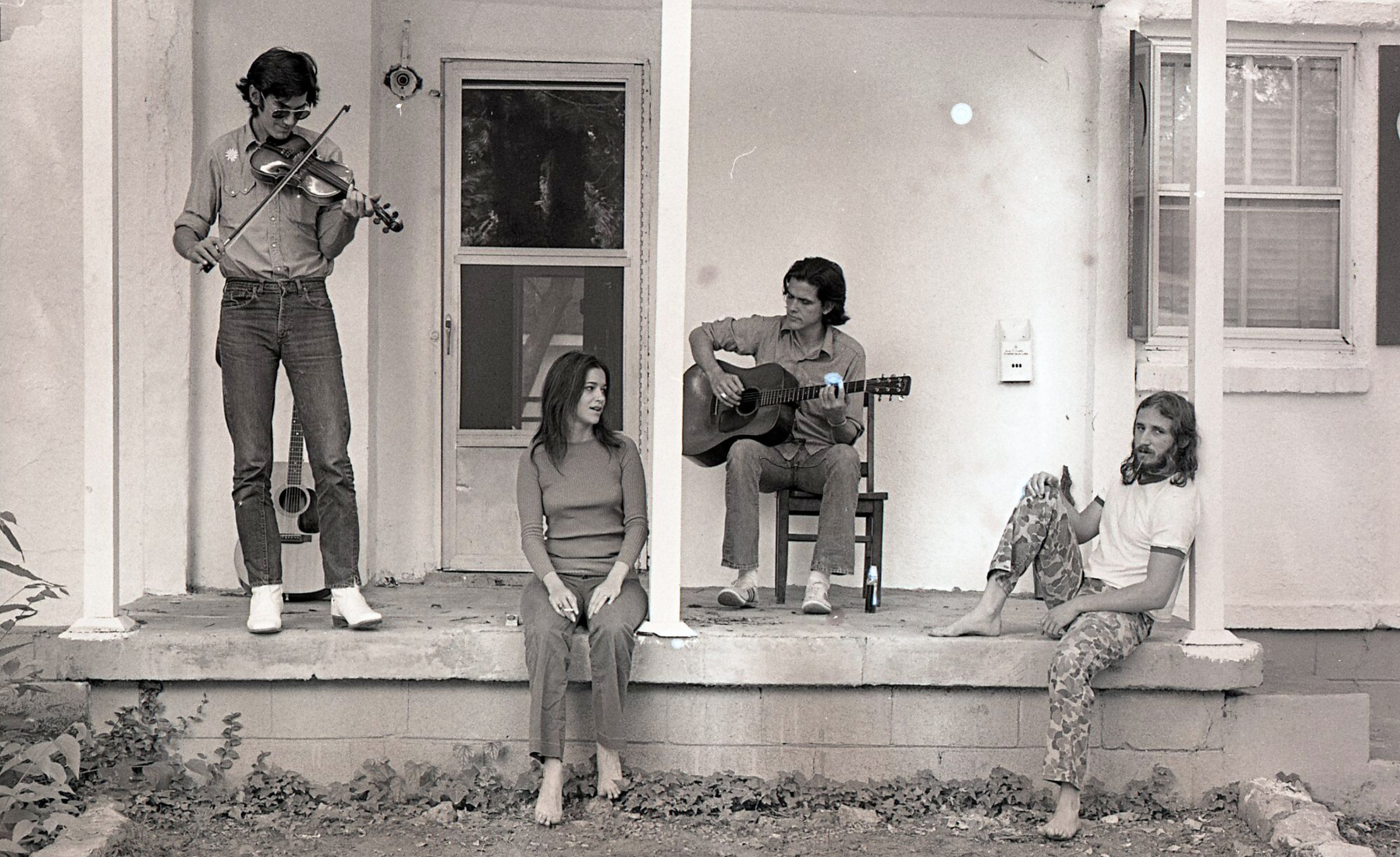

Clayton started his career in Nashville in the ’60s photographing musicians on tour and behind the scenes. He also shot more than 100 album covers. Jennie has fond memories of people like Kristofferson, Townes Van Zandt and Waylon Jennings coming over for backyard barbecues. Many of those images, some of which had never been seen before, were used in Ken Burns’ “Country Music” documentary series that aired on PBS in 2019.

Now some of those photographs are destined for icon status. They are emblazoned on a line of T-shirts produced by Hi Fidelity Entertainment, a San Francisco-based company that specializes in licensed apparel for the music industry. Among the musicians featured are Tammy Wynette, Earl Scruggs, Kristofferson, Jennings and Van Zandt. A second series including Johnny Cash is planned later. And each shirt will bear Al Clayton’s signature.

“They’re beautiful images and in many cases, they have not really been seen on merchandise before,” said Howard Schomer, the company’s CEO and founder. “Obviously Al shot these at a period of time that is very evocative for all the artists. They’re just classic images.”

The T-shirts will be available for purchase in museum shops, record stores, Nashville tourist spots and e-commerce sites in April, he said.

Jennie admires her father’s music photographs, but her favorite photograph he took is the one called “Joe C.” from his series of homeless people. She’s like her father that way.

“People like Joe were a lot more interesting to him than Johnny Cash ― and he really liked Johnny Cash,” she said. “He was a lot more interested in the average. Fame did not impress him.”

Ultimately Jennie would like to see her father’s prints and negatives secured in a university archive. But for now, she takes pleasure in seeing his images out in the world again.

“His work was too important to leave it sitting in a file cabinet. The world needed to see it,” she said. “It was something that was really, really important to me ― that people see what impacted the man that impacted me.”

Although she spent her childhood around the darkroom and surrounded by her father’s photography, Jennie rarely peered through a viewfinder to take her own pictures until after he died.

“I didn’t pick up a camera until 2016, and now that’s what I make a living as,” she said.

One might say she has big shoes to fill, but on the other hand, she’s been in training her whole life.