By 1860, the importation of slaves into the United States, illegal more than a half-century, is a federal offense punishable by death. But for Mobile, Alabama’s Timothy Meaher — boat builder, lumber baron, wily river pilot — the rule of law won’t pose much of a threat: he’s a volatile Southern fanatic who’s stuffed the city’s pro-slavery newspapers and judiciary into his back pocket.

Boasting his intention to dodge the U.S. Navy’s enforcement of the hated ban, Meaher partners with William Foster, a shipwright who captains his beautifully crafted schooner, the Clotilda. The pair modifies the vessel, and, by the time it embarks from Meaher’s “private port” in the swampy wilds north of the city, the ship’s hold will have an enlarged capacity for 130 human beings.

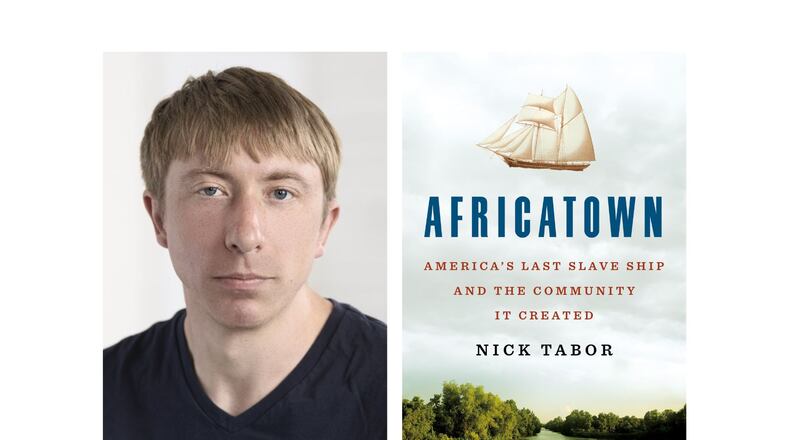

Thus, we have Nick Tabor’s panoramic historical account, “Africatown,” which opens as a tale of distant kingdoms connected through time and space by evil transaction.

Foster’s destination is, of course, West Africa, where a shrewd and violent king rules Dahomey, a warlike precinct nestled within the otherwise peaceful Yorubaland region. Happy to accommodate rogue American slave traders, the king sells the captives he’s seized from raids on neighboring tribal groups.

Kossulo, an unskilled, “provincial teenager,” is imprisoned in one of Dahomey’s barracoons — ”earthy jails” made of poles. He can’t imagine that, within weeks, he’ll be transported from Africa’s Slave Coast to America’s Gulf Coast, where he and 112 of his fellow prisoners, later known as the “shipmates,” will be “marooned” for the rest of their lives.

On arrival in Alabama, the slaves are hastily dispersed among several plantations, the majority going to Tim Meaher and his two brothers, and to Foster, who burns the Clotilda, sending it to the bottom of a channel up the Mobile River by Twelve Mile Island. “The Last Slave Ship” becomes a sunken legend. Did it ever really happen?

Surviving the Civil War, the African-born slaves begin purchasing land in nearby towns like Plateau and Magazine Point during the Reconstruction era. They “[teach] the American-born freed people how to live independently,” writes Tabor, but they’re often ridiculed for their unfamiliar Yoruban ways. They assume “outsider names”: Kossula, for instance, becomes Cudjo Lewis (d. 1935), today revered as Africatown’s Ur-figure.

Gerrymandered out of Mobile’s basic services, they’re subject to disease, and, despite self-policing, denied the protection of law enforcement. (One of Cudjo’s sons dies of diphtheria; another is shot and killed.) In 1893, a journalist declares that they “can’t survive much longer.”

And yet, there are positive developments. A training school established in 1918 becomes an “academic powerhouse.” National journals begin to pay attention. The Harlem Renaissance author, Zora Neale Hurston, then a pioneering anthropological ethnographer and film documentarian, transcribes her extensive interviews with Cudjo Lewis circa 1928; rediscovered 90 years later, they’re published as “Barraccon: The Story of the Last ‘Black Cargo,’” a surprise 2018 New York Times Bestseller.

Nick Tabor, a New York journalist, relocated to Mobile in 2018 to pursue this story. He made friends throughout Africatown and lost himself in the city’s archival dust mote. His book tracks the Gulf port’s economic development from its antebellum days as a filthy, if cosmopolitan, boomtown, through its role in the New South’s industrial transition from “King Cotton” to “King Pulp” during the 20th century.

Nearly powerless, Africatown’s domain is gradually encircled by unregulated heavy industry, Southern-style. Their communities become “sacrifice zones,” a textbook case of “environmental racism,” a useful (and accurate) term coined by sociologist Robert Bullard (“Dumping in Dixie,” 1990), cited by Tabor.

Perforce, the enormous International Paper mill appears in 1928, blanketing the communities in torrents of “flaky white ash.” Over the decades, Scott Paper and various chemical and industrial plants follow, often leasing or buying land from the Meahers. Stupefying quantities of dioxin, hydrochloric acid and chloroform are released. Servile judges allow the area’s waterways to become “industrial streams.” The fish die and the drinking water is contaminated. Residents contend with rising cancer rates.

More in the present day, Tabor reports a deepening concern that the pipelines and tank farms bordering Africatown are vulnerable to a far greater disaster than BP’s Deepwater Horizon spill. In response, Africatown’s scrappy environmental coalition, a diverse alliance that includes Native Americans, the Sierra Club and white Mobilians, meets with some success in their fight to save both themselves and Alabama’s entire coastal region from petroleum hell.

In 2018, the remains of the Clotilda are found by the intrepid writer/diver, Ben Raines, 168 years after it was sunk by William Foster.

The Ambassador of Benin, formerly Dahomey, travels to Alabama to deliver a weeping apology, begging forgiveness for his country’s role in the descendants’ ordeal.

The same cannot be said for the wealthy Meaher clan, which still has extensive holdings in Africatown. Many believe that in the 1970s, the secretive family dynamited the Clotilda’s remains to retrieve and sell off its copper bottom. They refused to be interviewed for Tabor’s book.

Nevertheless, the announcement of the Clotilda’s discovery becomes an emotional event of monumental importance for Africatown’s population, a bittersweet celebration accompanied by calls to expand the “heritage tourism” business and to realize the vision of a “blueway” path throughout the riverine community.

From their first footfall in the Alabama canebrakes, the Clotilda “shipmates” carried themselves with yogic dignity, as have their descendants. Beaten down but never beaten, “Africatown” is their story. Visitors come to verdant spots like the restored Plateau Cemetery, where Cudjo’s weathered stone marker suggests an old and lonely sentinel yearning for his faraway home.

NONFICTION

“Africatown: America’s Last Slave Ship and the Community it Created”

by Nick Tabor

St. Martin’s Press, 384 pages, $29.99

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured