When Lynn Cullen was growing up the sixth of seven kids, her family vacations were camping trips at historical sites all over the country. Learning weird facts was an integral part of the fun, and the payoff was a constant sense of discovery.

“We were ingrained to look for history, to look to the past for clues about today,” she says. “My father was not a wordsmith; he was an electrical engineer. But he really instilled in us a sense of wonder at the world.”

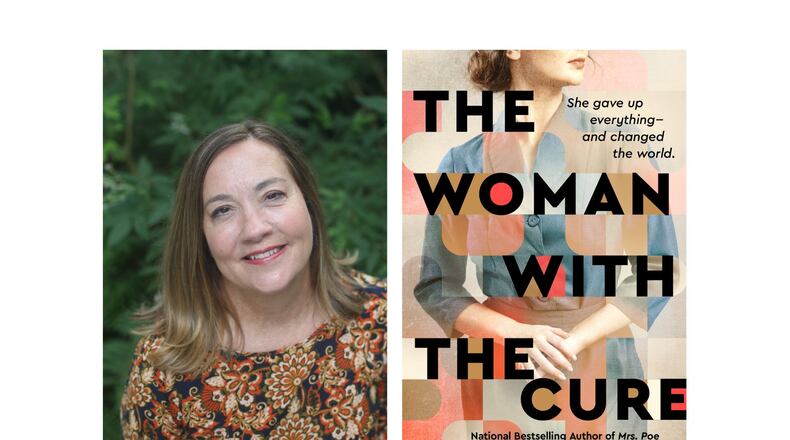

Those habits have held Cullen, 67, in good stead as Atlanta’s foremost historical novelist, with six books to her credit, all about misunderstood or overlooked women.

“Setting herstory straight since 2008,” as she likes to say, her work has been compared with the process of art restoration, the way it reveals previously unnoticed — but vibrant and important — pieces of the painting.

Traveling to the places where her subjects worked and played, she plunges into meticulous research. Guided by deep reserves of empathy, she finds the telling details that evoke the past, whether it’s gas-lit lamps or Tabu perfume.

Cullen’s books include “The Sisters of Summit Avenue,” " Twain’s End,” “Mrs. Poe,” “Reign of Madness” and “The Creation of Eve.” She has appeared on PBS American Masters, and her novels have been translated into 17 languages.

Her most recent work is “The Woman with the Cure” (Berkley, $17) about Dr. Dorothy M. Horstmann, an epidemiologist, virologist and pediatrician, whose research on the spread of poliovirus in the bloodstream laid the groundwork for the development of the polio vaccine.

“Everyone knows (Albert Bruce) Sabin and (Jonas) Salk created the polio vaccine, but without the work of Dr. Dorothy Horstmann, there never would have been a vaccine in the first place,” says Bonnie Garmus, author of “Lessons in Chemistry.” “So huge applause … for reminding us that women have always been in science — despite those who would pretend otherwise.”

Cullen initially got the idea for the book during a tour of the Centers for Disease Control. “I was learning about these heroes of public health, and the thought occurred to me, as it often does: Where are the women?” she says. “When that resounding alarm sounds in my head, it usually means I’m about to head down a rabbit hole. It really helps if I find a lovable person, someone who is kind.”

When she saw a Life magazine photograph of a strikingly tall woman working with polio-afflicted children in Hickory, North Carolina, Cullen knew she’d found a clue. It was Horstmann, a woman seemingly not driven by ego like the men in her orbit, a scientist who simply wanted to save children.

“There was also a 1951 photo of her with several men, which is maddening because it looks like she’s taking dictation when they probably should’ve been taking dictation from her,” Cullen says. “You’d think she’d be front and center, but no.”

Well, she is now. And the timing of the book — in the wake of a different deadly pandemic and at a time when educators are encouraging girls to pursue STEM classes (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) — could not be more opportune. The experience of reading the novel is a bit like watching the movie “Hidden Figures.” How vital and delightful that these innovators pursued their callings against long odds, but how frustrating that we are only just now learning about them.

“In ‘The Woman with the Cure,’ Lynn manages to distill complex science while capturing the headiness of discovery and the urgency to stop a pandemic,” says Amanda Bergeron, Cullen’s editor at Berkley Books. “She takes the time to understand the world her characters lived in, to pose questions and bring context and richness into her depictions so the reader can get swept up in the story knowing they are in good hands. I fell in love with both her emotional, relatable portrait of Dorothy Horstmann, a woman I knew nothing about — though we all should know about her — and for the way Lynn made this past era feel relevant today.”

A native of Fort Wayne, Indiana, Cullen’s first crush was Abraham Lincoln.

“He was the original kind person for me,” she says. “I loved going to the museum.” She gravitated early on to what would become her calling. “I skipped Nancy Drew,” she says, “and went straight for historical biography.” She eventually studied English at Indiana University.

In 1983, the year her youngest of three daughters was born, Cullen and her husband moved near Decatur, where she began to write children’s literature.

“I wrote 10 books for kids, both novels and picture storybooks, when my three daughters were young, between ferrying them to soccer, dance, basketball, wherever and working part time in a pediatric office,” Cullen says. “I wanted to write stories for both girls and boys that made them laugh and made them think. Dogs found their way into most of them, as did history. Thinking about it, writing for kids was a great fit at that stage of my life because they incorporated three of my great loves: children, animals and history.”

She got a teaching certificate and took a few writing classes at Georgia State University. “I worked as a middle-grades teacher but gave it up to write — something had to give! Mostly, my writing is self-taught, guided by what I learned about story structure and themes from literature courses and from observing life — and working really hard.”

She also plays hard.

“I’ve actually done some crazy things in the name of my books,” Cullen says, shaking her head. “I was guest of honor at the costumed Black Cat Ball, the highlight of the Poe world for scholars and fans alike, in October for ‘Mrs. Poe.’ When ‘Mrs. Poe’ came out, I led a ghost tour of Poe’s haunts by candlelight in Greenwich Village, but what was really spooky was when I wandered in Mark Twain’s Victorian mansion in Hartford, Connecticut, alone, for a half hour, in the dark, when the power went out before I gave a talk there.

“But probably the funniest thing I did was to appear at the Atlanta Pug Fest to promote (my children’s book) ‘Moi and Marie Antoinette’ and was surrounded by thousands of snorting pugs in costumes. I still laugh, thinking about that.”

Atlanta writer Ann Hite met Cullen at the Townsend Prize ceremony in 2012. “I treasure her as a mentor and influence,” Hite says. “My approach to writing has evolved in a good way from reading her novels. Mostly, she is pure fun to be with. Writers spend a lot of time in front of screens and alone with characters. When we meet up at events, Lynn is always the life of the party.”

Adds Joe Davich, executive director of Georgia Center for the Book, “Lynn is a gentle and generous spirit. The care she shows with her characters is simply an extension of her own personality. If she is not digging into history to write a better story, she is digging into a conversation with a fan at a book signing or engaging with other authors. Her love of writing and history are genuine and can be felt.”

Cullen’s father died in 2000, before she began writing historical fiction.

“He was excited that I published children’s books, but he would have loved that I found my voice as an author by writing novels that explored history, as he’d taught me,” she says. “My initial thought when I held my first historical novel was of him. How I wished he could have read the culmination of his teaching.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured