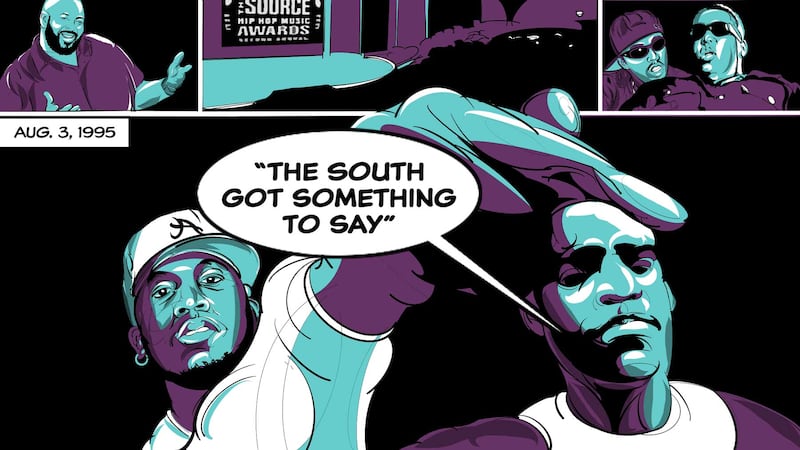

The oral history of ‘the South got something to say’

How André 3000 and the 1995 Source Awards planted a flag and changed rap music

On the evening of Aug. 3, \, André 3000 and Big Boi, the baby-faced members of a scrappy rap group out of Atlanta called OutKast, walked into an already simmering conflict.

It was the 1995 Source Awards, a defining moment in hip-hop culture’s history, on its most defining night.

On one side was the West Coast faction, led by Suge Knight, Snoop Dogg and the Death Row Records posse. They had forged their way into New York City’s Paramount Theater at Madison Square Garden to violently wrestle away the East Coast’s rap crown, which at that time firmly rested on the heads of The Notorious B.I.G. and Sean “Diddy” Combs.

André and Big Boi sat in the audience, waiting for the announcement of the new artist of the year (group)” award, for which they had been nominated for their debut album, “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik.”

Jermaine Dupri was there. So were members of the Dungeon Family, the Atlanta-based hip-hop collective that also included the Goodie Mob.

But they were almost invisible to a crowd whose interests at that time were mostly bi-coastal.

Who cared about a bunch of rappers from Atlanta?

They watched quietly as the conflict between East and West Coast factions of hip-hop music came to a head.

When Salt-N-Pepa, the seminal female rappers, announced over boos that OutKast had won best new group, Big Boi and André 3000 sensed an opportunity.

Big Boi spoke first. Then he handed the microphone to André 3000, who with a very simple phrase, declared to a somewhat hostile audience: “The South got something to say.”

Atlanta rapper T.I., who watched from home, called this event a “battle cry.” Lil Yachty, who wasn’t even born yet, called it rap’s “I Have a Dream.”

“You can’t talk about Southern hip-hop without talking about that night,” said music industry veteran Shanti Das, who was in the audience that night. “It was one of the biggest moments in hip-hop history.”

It was indeed the start of something good. This is an oral history of the origin, and evolution, of Atlanta’s influence on rap music and its culture.

Starring:

Speech: Founder of rap group Arrested Development; Pete Nice: Co-curator for the Hip Hop Museum; Keisha Lance Bottoms: Former Atlanta mayor; Mayor André Dickens: Atlanta mayor; Ryan Cameron: Nationally syndicated radio personality; Shannon McCollum: Photographer; Jermaine Dupri: Founder of So So Def Recordings; Benzino: Former owner of The Source Magazine; Mojo: Atlanta’s first known rapper; Joycelyn Wilson: Assistant professor of hip-hop studies and digital humanities at Georgia Tech; Keinon Johnson: Senior Vice President at Interscope Records; T.I.: Atlanta rapper; Rico Wade: Organized Noize producer; Shanti Das: Marketing executive; Killer Mike: Atlanta rapper, activist; Sydney Margetson: Music executive; Kawan “KP The Great” Prather: Music executive, producer and deejay; Sonia Murray: Pioneering hip-hop journalist; CeeLo Green: Member of Goodie Mob; Big Gipp: Member of Goodie Mob; T-Mo: Member of Goodie Mob; Jason Orr: Arts curator; Ray Murray: Organized Noize producer; Maurice Hobson: Author, “The Legend of the Black Mecca: Politics and Class in the Making of Modern Atlanta”; Princess: Atlanta rapper; Lil Yachty: Atlanta rapper; Jordan Victoria: Founder, Silk Tymes Leather; Jeezy: Atlanta rapper; Tory Edwards: Owner, Atlanta Influences Everything; Fahamu Pecou: Atlanta visual artist; Sen. Raphael Warnock: Pastor Ebenezer Baptist Church; Amir “A.R.” Shaw: Author, “Trap History: Atlanta Culture and the Global Impact of Trap Music”; Rocky Bucano: Director, Hip Hop Museum; Kasim Reed: Former Atlanta mayor; Khujo: Member of Goodie Mob

Featuring

André 3000 of OutKast; Big Boi of OutKast; Salt-N-Pepa; Suge Knight: President of Death Row Records; Snoop Dogg: Iconic rapper

— AJC Intern Shahid Meighan contributed to the writing and researching for this oral history.

— Editor’s Note: Parts of the following quotes have been edited for length and clarity.

Track I - Where is Atlanta?

Prior to 1995, Atlanta and the South were afterthoughts in the rap world. New York, which had birthed the genre in 1973, and Los Angeles, which had pioneered gangsta rap, were vying for dominance and had introduced the world to artists who went on to become household names in the culture.

But a hunger was brewing in the South.

Rap artists with a distinctively Southern sound were tired of being left out of the hip-hop conversation. They were ready to make it known, not just in the United States, but across the world, that recognition was long overdue, and they were taking theirs.

In 1995, OutKast dropped their first album, “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik.” With its live instrumentation, and heavy funk and soul influences, it instantly became a classic with tracks like “Player’s Ball” and “Git Up, Git Out.” Critics adored it, including Benzino’s powerful magazine, The Source. But instead of awarding it a perfect five “mics” in its revered rating system, The Source couldn’t stomach giving such praise to a non-New York group. So they settled on 4.5 “mics.”

Track II: August 3, 1995 - The Source Awards

Despite the lack of respect and getting only 4.5 mics, OutKast was invited to the 1995 Source Awards as a nominee for the new artist of the year (group) award, against Bone Thugs-n-Harmony, Ill Al Skratch and Smif-N-Wessun. Brooklyn emcee The Notorious B.I.G. would win “new artist of the year (solo)” and his “Ready to Die” beat OutKast’s “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik,” for rap album of the year.

Seating Charts

In 1995, The Source Awards was still only two years old, but was already the most important rap event of the awards season. The Atlanta delegation, primarily the Dungeon Family, made their way to Madison Square Garden, “The World’s Most Famous Arena.”

“It could’ve went down”

Throughout the night, the two coasts battled. Snoop sneered, cursed and riled the already agitated New York crowd to near delirium when he defiantly asked them over the boos: “Y’all don’t love us?”

Suge Knight, dressed in a red shirt (likely signaling his known gang affiliations), took a direct verbal shot at Combs, telling “any artist” to “come to Death Row,” if they didn’t want to worry about their executive producer “trying to be all in the videos, all on the record, dancin’.”

After it was announced that Biggie won best new solo artist, Salt-N-Pepa and Kid ‘n Play walked onstage to present new artist of the year (group). Christopher “Kid” Reid opened the envelope and asked Salt-N-Pepa to “help me out.” They seemed bothered by the request, barely looked at the card and drolled, “OutKast.”

Why y’all booing?

André led what was essentially the Dungeon Family — OutKast, Goodie Mob and Organized Noize —onto the stage. As the boos grew louder, André clapped. It was a hard clap. A clap of defiance. He walked past the microphone, still clapping. His trademark smile was long gone. Replaced by something bordering on rage and fear. Big Gipp smiled, showing the audience a mouth full of grills.

When the full crew finally gets on stage, Big Boi, wearing a road gray Atlanta Braves jersey, speaks first.

Boom

Track III: What is the South Saying Now?

On Nov. 7, 1995, three months after the 1995 Source Awards, Goodie Mob, whose members had stood onstage that night behind OutKast, released their debut album, “Soul Food,” featuring one of the songs that helped define Atlanta’s sound, “Cell Therapy.” In August 1996, a year after André 3000′s announcement, OutKast released their second album, “ATLiens.” The Source gave it five mics.

A month later West Coast rapper Tupac Shakur, who wasn’t at the 1995 Source Awards, but who would emerge as a central figure in the East-Coast-West-Coast conflict, was gunned down in Las Vegas. In March 1997, a hail of bullets brought down Biggie in Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, OutKast marched on in quick succession with “Aquemini,” “Stankonia,” and the massive double album, “Speakerboxxx/The Love Below,” which earned the group a Grammy for album of the year. To date “Speakerboxxx/The Love Below,” has sold more than 13 million copies, making it the biggest-selling hip-hop album of all time. They would also go on to win six Grammys.

In the months and years following 1995, Southern rap artists would go on to become global icons. T.I. rose out of the trap houses of Bankhead to pioneer trap music, bringing Jeezy and Gucci Mane with him.

Ludacris became a bonafide movie star, and Lil Nas X boldly explored country music and his sexuality.

The Ying Yang Twins, Pastor Troy, Lil Jon, Crime Mob, Rasheeda and Three 6 Mafia went on to popularize crunk music in the South. Killer Mike, Future, Migos, 21 Savage, Latto, Baby Tate, Lil Yachty and Lil Baby — all hailing from Atlanta — run hip-hop today.

These household names and new faces in the culture served as the fulfillment of André 3000′s prophecy:

“The South got something to say.”

The Aftermath

Race & Politics

The Trap

But not everyone is happy with the direction that Atlanta is going. Trap music, which was popularized by T.I. as a reflection of life in and outside of drug houses — as an act of hustling and grinding for financial gain — is the dominant form of music coming out of the city now.