When you talk to many of the key players in Atlanta’s hip-hop scene, a theme quickly emerges: The South has always had something to say but the titans of the music industry haven’t always been ready to listen.

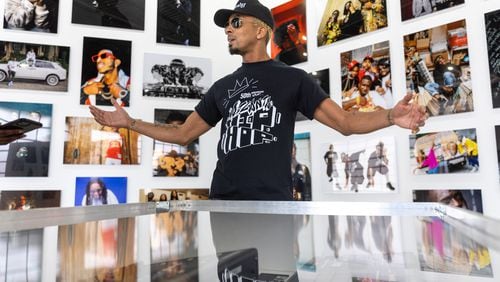

“It could be my fault,” said Jermaine Dupri when we talked just after the opening of the “Atlanta 50 Years of Hip-Hop Experience,” a pop-up exhibition at Underground Atlanta created by Dallas Austin and Dupri to pay homage to Atlanta’s rise to the top of rap and hip-hop culture.

The story begins in the 1980s, when indie record labels and local artists set the foundations of Atlanta rap. By the mid-1990s, Atlanta’s music industry was on the fast track and Dupri was at the forefront with So So Def Recordings, his production company and record label focused on southern hip-hop and R&B.

Dupri admits he wasn’t concerned about corporate dollars or courting the kind of partnerships that would build the city’s music infrastructure. He said he did everything on his own and used his own money to pay for it — the So So Def billboard that cost $10,000 per month, travel expenses to fly media into the city for listening parties, videos that he paid to film out of state because back then you couldn’t just drum up a film crew in metro Atlanta.

Credit: AJC

Credit: AJC

“We never got the memo in the South that we should be having meetings with corporate America to get them to pay for things that we wanted to do in hip-hop, so that structure isn’t set up,” Dupri said.

“When you go to Nashville, they have BMI, SONY … for some reason, those companies never took the initiative to build an office in Atlanta. It still hasn’t changed,” he said. “Atlanta has always been handicapped when it comes to the other pieces of the music industry.”

Atlanta has been called the epicenter of hip-hop, the hip-hop center of gravity, the center of the rap universe and the rap capital. Much of that power is concentrated in Fulton County which accounts for one-third of the state’s music industry, according to a recent study from Georgia Music Partners and Sound Diplomacy.

With more than 130 recording studios as well as rehearsal spaces, performance venues and music organizations, the city seems to have the makings of an ecosystem that could support the city’s indomitable hip-hop industry, but when it comes to access to deals, access to funding and a central district that reflects the city’s most notable music genre, industry experts say Atlanta got left behind.

“When I go to New York, Los Angeles, Nashville or Toronto, all those cities have spaces, buildings and C-suite executives on the ground that have the power to create deals,” said Richard Dunn, the serial music entrepreneur who has worked in production and promotions with a range of artists. “I never got a check from the music business that didn’t say Broadway or Wilshire. Nobody is writing checks on the music side that says Peachtree Street.”

In a city known for Black music, Dunn said, policy and funding haven’t supported the hip-hop industry in the same way it has for other industries like film, technology or transportation.

Where is the Atlanta version of Nashville’s Music Row or the live music scene in Austin? Why are aspiring music industry executives just out of school still leaving Atlanta for jobs on the coasts?

Credit: TNS

Credit: TNS

Politicians and chambers of commerce go out of their way to pursue corporate headquarters or global sporting events, Dunn said. It’s time they did the same for music.

“We need some intentional advocacy from those who spend their time and talent making sure Atlanta has an industry,” he said.

According to insiders, and in accordance with Dupri’s acceptance of guilt, some of the obstacles blocking the development of the hip-hop industry in Atlanta are self-created. When hip-hop began its rise in Atlanta, the entire scene felt like a community, said music industry publicist Tresa Sanders.

LaFace Records was at its peak in the city during the 1990s and with a growing number of independent labels, Atlanta had the capacity to develop and train music industry executives who could support the growing talent pool of artists.

Atlanta was becoming a force in the music industry even as the city played catch-up to the more established systems in Los Angeles and New York.

Atlanta’s success was largely due to the city’s population growth, easy access to a range of talent and its affordable cost of living compared to other major music hubs in the U.S., but there was no strategy for the music industry from an economic perspective, according to the strategic plan from Sound Diplomacy and Georgia Music Partners.

Then, Sanders said, there was a break. In 2000, LaFace Records left town. The music community grew more fractured as different styles of hip-hop — trap, crunk, snap and others — began to evolve. “It was very compartmentalized and there was no bridge,” Sanders said.

Different artists cultivated their own brands and identities, said hospitality consultant Dona Mathews. “The music industry has very few rules,” she said. “[Artists] built themselves up with no infrastructure and no support.”

The city had begun to feel like a place where artists came to make music and make names for themselves but important decisions about that music were being made in other cities.

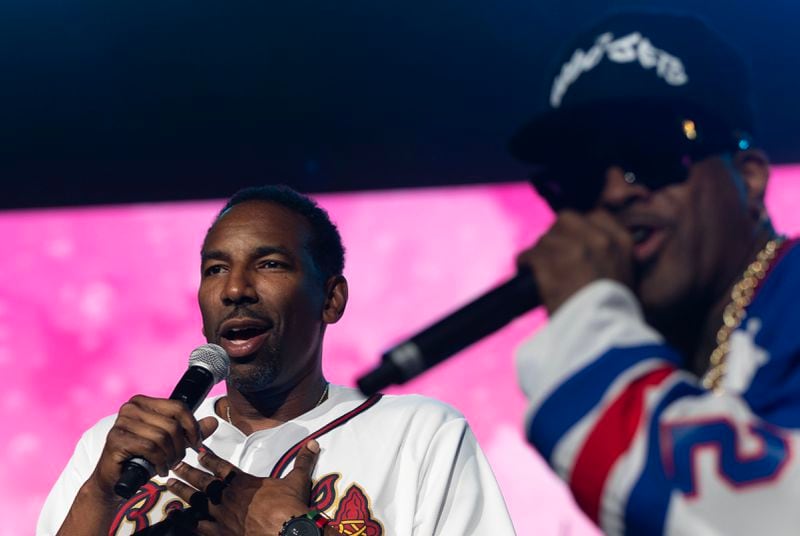

“That’s a problem,” said Cannon Kent-Grant, national director of promotions for Atlantic Records, in a recent interview for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s forthcoming documentary, “The South Got Something To Say.”

Kent-Grant, who serves as a board member for the Recording Academy’s Atlanta chapter, said the organization is working on bringing more support to Atlanta-based studio owners and artists, as well as finding ways to make sure that roles like engineering and sound mixing use Atlanta-based technicians rather than professionals from other cities.

A lot of people are working from the legislative side to empower musicians, she said, but bringing decision-makers to Atlanta would be game-changing for the city.

While artists have generally been supportive of one another, with rappers pulling up a stream of proteges behind them, that same spirit of collaboration has been harder to come by in the broader music community.

“We often work in silos,” said Phylicia Fant, head of music industry partnerships for Amazon and former head of urban music for Sony Music’s Columbia Records. ”We have to come together to say this is the music business plan for Atlanta. We have to create a joint infrastructure that everyone is part of. There needs to be an understanding from the top down that says we are committed to Atlanta.”

If ever the city has been ready to make that commitment, it is now, said Phillana Williams, director of the Mayor’s Office of Film & Entertainment and a 20-plus year veteran of the music industry.

“When it comes to the talent pool, Atlanta far exceeds any other part of the country,” she said. “When it comes to our brick-and-mortar businesses and music, we could be doing a lot better.”

Just a week into his term, Mayor Andre Dickens approved Williams’ request to create a nightlife division that would be instrumental in building the kind of music entertainment district the city lacks. “[Mayor Dickens] understands the culture, the importance of it and what it means to the fabric of the city,” said Williams.

Credit: Michael Blackshire

Credit: Michael Blackshire

Williams, who worked at LaFace Records before moving to New York and Los Angeles for jobs that didn’t exist in Atlanta, knows well the importance of centering the music business in Atlanta.

The city is working on local entertainment initiatives that will encourage businesses not just to do business in Atlanta but to choose Atlanta creators for jobs, she said.

After an exploratory trip to understand Nashville’s music ecosystem, city officials are looking into what it would take to develop a comparable system in Atlanta. Williams said the city is engaging a research team to put together a proposal.

Already, there are signs that things are changing in Atlanta. While major entertainment agencies and music labels have had satellite offices in Atlanta, early this year, United Talent Agency opened a full-service office on Peachtree Street.

In its first big splash, the agency is hosting an inaugural summit, “UNLOQ404″ in October, giving local creators the opportunity to network and learn from industry experts.

“UTA, representing storytellers who drive culture and shape the future, purposely opened an Atlanta office for moments like these — to provide institutional support and infrastructure to those shaping the next cultural wave… and the results will reaffirm Atlanta’s influence on the world,” said Steve Cohen, agent and co-head of UTA’s Atlanta Office, in a press release.

Credit: BEN GRAY

Credit: BEN GRAY

Part of the challenge in building a traditional music and entertainment network in Atlanta that mirrors those that have long existed in New York and Los Angeles is that the landscape of music is different. Artists don’t always need labels and agents to get their music to the masses but consumers still need multiple avenues to experience music, said J. Carter, founder of ONE Musicfest.

Live music, in particular, is expensive to produce and you can’t support a live house band on $5 drinks, he said. Carter envisions a team of developers, city officials, creatives, producers, studio owners and cultural ambassadors all sitting down together to decide what needs to be done, and how to execute it in Atlanta.

“If there were breaks and benefits, I would reach back out to my old partner from Sugar Hill and say, ‘Let’s get this thing back rolling,’” said Carter who co-owned Sugar Hill, a nightclub and music venue (along with the aforementioned Richard Dunn and other partners) at Underground Atlanta that became a popular stopping point for Black musicians passing through the city.

And that brings us full-circle back to Underground Atlanta, where the 50th anniversary hip-hop experience pop up curated by Dupri and Austin reminds us of all Atlanta has accomplished and offered to the world of hip-hop and why it’s time industry executives should take heed.

About the Author