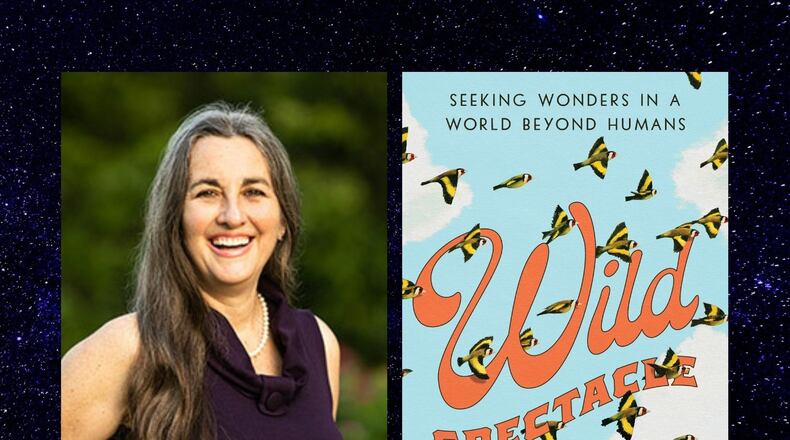

Well-crafted nature writing has an intoxicating effect on me, and nobody makes me swoon like Janisse Ray. Her new book of essays, “Wild Spectacle” (Trinity University Press, $24.95), is an enthralling immersion into the splendor of our natural world told in language that is equal parts rapturous and down to earth.

“Exaltation of Elk” is a heart-pounding tale about a startling encounter with a herd of elk in the backcountry of Montana. “Las Monarcas” recounts a sobering trek through a butterfly sanctuary in Mexico where the ground is littered with 200 million dead Monarchs. “The Dinner Party” tells of a month-long retreat on the remote Alaskan island city of Sitka that ends with a convivial four-hour feast, locally sourced, featuring herring eggs on kelp, salmon and huckleberry cobbler. “The meal was a crescendo, an arc of a bridge; and in its shining I could satiate my insatiable cravings for a wilder world,” she writes.

Honestly, why Ray hasn’t been showered with all the literary awards, I’ll never know.

“Wild Spectacle” is her first book of nonfiction in 10 years, and it features older essays, some dating back to the early 2000s. It’s not that she hasn’t been writing since the 2012 publication of “The Seed Underground,” but she did stop publishing for a while. In the interim, she adopted her 6-year-old niece whose family, Ray said, “imploded.”

“I stepped out of the whole writing game,” said Ray. “I was just trying to save a kid’s life.”

Ray’s dry spell ended in April with the release of the poetry collection “Red Lanterns,” followed by “Wild Spectacle,” which becomes available Oct. 26. The timing is fortuitous. Ever since the COVID-19 pandemic, people have been flocking to wilderness areas in large numbers. Sadly, all that attention has had a detrimental effect, said Ray.

“We are putting a lot of pressure on our natural areas,” she said, speaking en route from her home in South Georgia to Oxford, Mississippi, where she was speaking at the Southern Foodways Alliance fall conference. To illustrate her point, she recounted a recent visit to Dolly Sods Wilderness in the Allegheny Mountains of West Virginia that she likened to the foggy bogs of Scotland.

“These trails had been so used by people that a trail that should have been a foot wide that meandered through this wild, strange country was 12 feet wild, eroded and muddy. The place was being loved to death,” she said.

“If this is the trend, if we’re all going move to cities — and let’s face it, when you live in the country you don’t need to go hiking and camping — if we’re going to continue this migration to cities, then I think we also need to preserve a lot more land and think about carrying capacity so that we don’t just ruin these last great places that we have.”

Carrying capacity — the number of people that can visit a wilderness area without damaging it — is a big concern, said Ray. She thinks there may come a time when access to national parks and other wilderness areas will be ticketed in order to control access. She suspects the effort will meet resistance because it treads on the idea of commons — those natural areas like parks, rivers and beaches that people feel a sense of entitlement toward.

“We feel we have a right to be on it when we want to be on it,” said Ray. “In this case we may have to make more restrictions, so we don’t destroy these last vestiges of wildness.”

Ultimately, Ray has faith humanity will do the right thing when it comes to protecting the environment.

“Not only are (more people) embracing getting out in the wild, but I think they are also embracing the numbers and the statistics and the science. Maybe our industry is not, maybe our government is not there yet, but it’s piling up, and it’s going happen,” said Ray. “The information for what we need to be doing to mitigate climate change is out there. People are reading it. We’re going to have policy changes, and we’re going to make a difference. I’m pretty sure of that.”

What “Wild Spectacle” contributes to the conversation is not statistics and science, but a heartfelt approach to the experience of nature.

“This book addresses the adaptation part,” said Ray. “It’s easy for us to go take a hike in a wild area on a Saturday afternoon, but maybe not so easy to really feel that we are the Earth and the Earth is us.”

That is one of the pleasures of reading “Wild Spectacle” — to see nature through Ray’s watchful eyes and ears. What I might experience on a Saturday hike as quiet and calm, she witnesses as teeming with activity. To achieve a greater level of observation, Ray recommends reading field guides and going to Audubon events, “so that when a great crested flycatcher calls, you might be able recognize it.”

Ray places great value on being able to name plants and animals and birdsong.

“If we can name our world, we’re so much deeper in it, I think. Naming gives you a deeper relationship with the thing. What I’m really after (is) intimacy — intimacy with other humans, but also big intimacy with the Earth. I believe that our ancestors keep walking around, they’re walking around with us. I want a deeper intimacy with that other world. So, I also recognize that ‘Wild Spectacle’ gets to that place, too, which is a kind of borderland, a visible but invisible borderland.”

Reading “Wild Spectacle,” I feel like I’m right there with Ray, traipsing along the trails of that borderland, and the view is absolutely magnificent.

Suzanne Van Atten is a book critic and contributing editor to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Contact her at svanatten@ajc.com and follow her on Twitter at @svanatten.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured