I had a student once in a creative writing class who wrote almost exclusively about fly fishing. I have no interest in that particular topic, but he didn’t really write about the sport. He wrote luscious prose poems about fish shimmering like jewels in the water, about a lifetime spent trying to capture something he could never truly possess, about the lessons he learned in the process of pursuing his obsession. I was intoxicated by his writing. He made me want to read about fly fishing all day long.

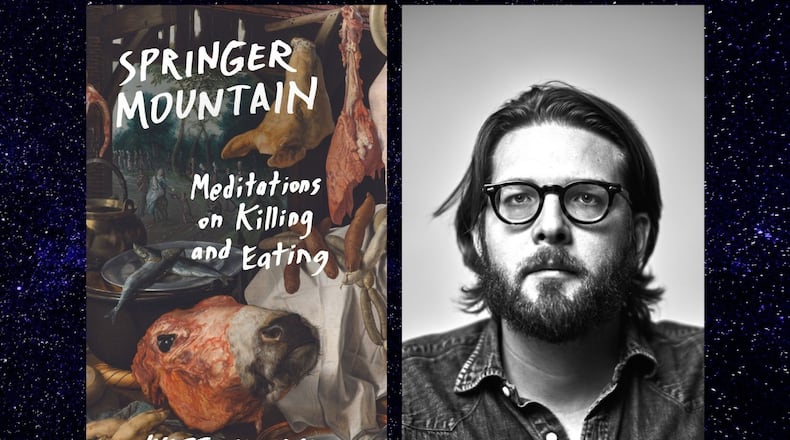

Wyatt Williams is like that. His slim new book “Springer Mountain: Meditations on Killing and Eating” (University of North Carolina Press, $19) is about consuming meat, and it is nothing if not contemplative. Despite the blood-and-guts subject matter, you can’t help being enchanted by the truth and beauty of the prose. Often melancholic in tone, it is also at various times naïve, arrogant and self-deprecating, but it is almost always captivating.

I confess to feeling preemptively squeamish when I began reading “Springer Mountain.” Although I consume flesh, I feel shamed by the act of violence required to deliver it to the table. It is that very dichotomy that anchors this three-part essay.

A former restaurant critic for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution who also worked at Creative Loafing and Atlanta magazine, Williams spent eight years researching, writing and rewriting “Springer Mountain.” The result is a mere 105 pages in which he weaves together intriguing bits of arcane history, literary excerpts, existential questions and observations about working on a farm, in a poultry plant and at a slaughterhouse. He also takes a morose visit to the American Museum of Natural History, irritates a famous actress over dinner at a restaurant in New York and fights with his girlfriend, who begs him to come back home and leave behind the farm where he’s gotten lost down a research rabbit hole.

What first sent Williams down that rabbit hole was a story he wrote for Creative Loafing in 2012 about Springer Mountain Farms. The chicken brand had become ubiquitous on menus at Atlanta restaurants that flaunted their locally sourced products from sustainable, ethical, cruelty-free farms.

“I was told Springer Mountain was a little family farm just north of Atlanta,” he writes. “I was told Springer Mountain raised the best chickens that Georgia had ever seen. I could not hear the name without picturing a creek running through a Blue Ridge forest. Where was this spring-fed paradise? I wanted to go there…”

What Williams discovered was that Springer Mountain was a marketing tool, a label slapped on chickens produced by Baldwin-based Fieldale Farms Corp., which claims to be the largest independent poultry producer in the world. When Williams visited, it was processing 250,000 chickens a day.

“The labels just told customers what they wanted to hear, what they wanted to believe about themselves,” Williams writes. “The farm I was looking for did not exist.”

I recently spoke with Williams from Iowa City. He’s teaching in the nonfiction writing program at the University of Iowa, which gave him a fellowship to finish his book. I asked him what it was about his Springer Mountain Farms experience that inspired him to spend eight years on the topic of meat consumption.

“It was a small thing to uncover, that one company was owned by another company,” said Williams. “That’s not the biggest revelation in the world, but the thing is, I’m really driven by secrets. ... Why did somebody not want for people to know that Springer Mountain was owned by Fieldale? And the bigger questions that come from that, why does someone want to do something secretive in relationship to what we eat?”

When Williams’ newspaper article was published, local restaurateurs took notice, but they didn’t stop proudly proclaiming that their poultry came from Springer Mountain Farms. That’s when Williams realized just how complicit consumers were in the mythology.

“There are a lot of things with agriculture that are tied up with our sense of self,” he said. “We want to be the sort of person that eats the good thing or the family-owned thing or the organic thing. There’s a certain kind of eater that, for example, wants to eat the luxurious thing. So why do we obscure where something is from? Why do we make it sound nicer than it is? I think it comes down to how do we think of ourselves and the person we want to be.”

Williams’ book ends with him on the receding coastline of an Alaskan village on the Arctic Ocean, roughly 1000 miles from the North Pole — a “place where the sun was spinning around in a circle in the sky and the cold wind was burning my face and gravel led to the end of the earth, where nothing ever seemed to rot or go away and history just piled up at your feet like so much junk.” There he eats whale blubber and ponders the clash between activists opposed to whale hunting and those who hunt whale to feed their families instead of buying packaged chicken shipped in from somewhere else.

If you’ve never thought much about where your food comes from and what it goes through before landing on your plate, you definitely will after reading “Springer Mountain.” And in the process, you will be dazzled by the writing.

Suzanne Van Atten is a book critic and contributing editor to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. You can contact her at svanatten@ajc.com and follow her on Twitter at @svanatten.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured