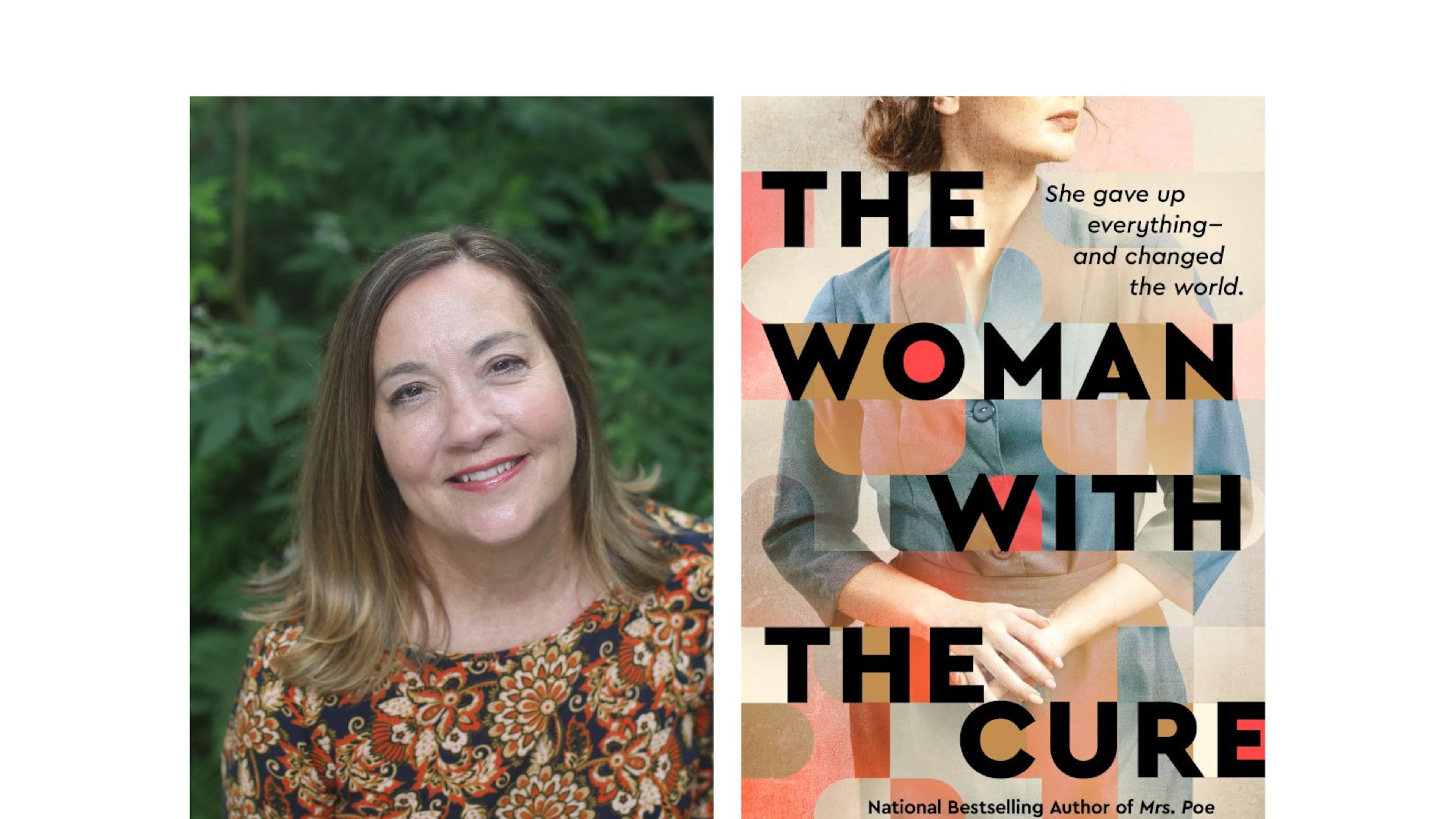

Book review: ‘Woman with the Cure’ explores sexism in the sciences

“The Woman with the Cure” by Atlanta author Lynn Cullen is an educational work of fiction following the life of historical figure Dr. Dorothy Horstmann, a scientist whose groundbreaking polio research in the 1940s and ‘50s paved the way for the disease-eradicating vaccine. By shining a spotlight on the contributions women have made to the STEM fields (science, technology, engineering and math), Cullen gives voice to a cadre of forgotten females who helped halt a virus that gripped the world for decades.

Cullen details in the acknowledgments how she adheres to history to tell the bigger, “albeit fictitious,” story of the women who appear in the record books of polio extermination. Without the work of Dr. Horstmann and Dr. Isabel Morgan, the accomplishments credited to the famed Drs. Salk and Sabin wouldn’t have been possible. Focusing on the struggle of Horstmann, a German immigrant who dedicates her life to pinpointing how poliovirus travels from the stomach to the nerves, Cullen has created a vibrant and driven portrait of a woman who refuses to be defined by convention.

A self-identified “Valkyrie in a Wagnerian opera,” Horstmann is uncomfortably tall. Her height is the first thing people comment on when they meet her. The second is she’s a female who doesn’t deserve a seat at the table. Women are expected to pour coffee instead of contribute to medicine in 1940. But every summer, thousands of children die or are paralyzed by polio, and the scientists in charge are more concerned with the glory of finding a cure than working together for the common good. So Horstmann persists.

Cullen does a powerful job layering the challenges Horstmann faces as she fights for relevance in a male-dominated industry. Constantly referred to as miss, not doctor, she’s only hired because her supervisor doesn’t peer past her initials to discern she’s a woman. She’s constantly skipped for promotions and every statement she makes, no matter how grievous, must be delivered with a smile — lest she not be taken seriously.

A cast of supporting female characters strengthen Cullen’s depiction of the constraints placed on women. Horstmann’s boss has a secretary with a Ph.D. in mathematics who spends her days pouring his coffee. Dr. Sabin, a man credited as a pioneer of polio research, has a disgruntled wife with an abandoned career in photography in her rearview. Perhaps the most frustrating to observe is Dr. Morgan — the first virologist to use a killed virus for inoculation in monkeys — who retires when she marries during the height of the pandemic because it’s not possible for a woman to have both a marriage and a career.

Dividing her narrative into 11 blocks of time that span from the 1940s through the ‘60s, Cullen opens each section with a different point-of-view character before refocusing on Horstmann’s plumb line. Her approach gives voice to a broad scope of female experiences, but it dilutes the impact a bit. Revisiting a few key players to see how their lives progressed could have revealed more about what the limitations placed on women cost them through the decades.

Cullen doesn’t shy away from exploring the ethical issues research scientists face, especially pertaining to animals. It’s particularly poignant when Horstmann visits the children’s polio wing before going to work in the lab. The tragic reminder that she’s ultimately fighting to save human lives is critical to her ability to keep experimenting on rhesus monkeys.

Passionate arguments erupt between the scientists regarding human vaccine testing. And Cullen addresses which sectors of the population, from the developmentally disabled to the imprisoned, were selected as early test subjects. Her exploration of vaccine development is informative and topical, given how relevant these issues have been recently.

While Horstmann is driven by her desire to save lives, she repetitively bumps up against male colleagues who are in it for the recognition. A million dollars is poured into an inefficient solution that results in 40,000 additional cases of polio. Meanwhile, it takes her decades to garner the clout required to command the funding she needs to conduct her research. Yet her results ultimately pave the way for successful vaccine implementation. Her frustration is well-rendered and palpable.

There’s an abundance of complex science packed into this narrative, much of it delivered as dialogue between characters, that could have been condensed. But Cullen effectively demonstrates how it took more than 30 years to eradicate polio largely because of male egoism.

Throughout the narrative, Horstmann remains a compelling and actualized character. In life she never married or had children. Nevertheless, Cullen gifts her with an endearing love story and uses it to showcase a man who respects a woman for her intellect and autonomy. Their relationship offers a refreshing break from the misogyny she battles in her professional career and illuminates the choices and self-sacrifice accomplished women have endured through the generations.

Another aspect Cullen uses to fuel Horstmann’s motivation is her tender connection to her family, hardworking German immigrants desperate to conceal their heritage as World War II wages on. There’s a lot packed into this narrative and much of it comes together to tell the compelling story of not just one woman’s plight to save the world, but the challenges so many faced in saving themselves and those they love.

“The Woman with the Cure” is a scrupulously researched history lesson wrapped up in a modern exploration of the evolving role women have played in society. Dorothy Horstmann and her contemporaries deserve their place in America’s medical hall of fame and Lynn Cullen’s resurrection has done them justice.

FICTION

“The Woman with the Cure”

by Lynn Cullen

Berkley

432 pages, $17